Tule

Scientific Name: Schoenoplectus acutus (Muhl. ex Bigelow) Á. Löve & D. Löve var. occidentalis (S. Watso

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | SCACO2 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Graminoid |

| Native Locations | SCACO2 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Bulrush, tule, black root. Known in some floras as Scirpus acutus Bigelow var. occidentalis (S. Watson) Beetle.

Uses

Ethnobotanic: Hardstem bulrush is similar to the cattail in edibility, although it is purportedly sweeter. Young shoots coming up in the spring can be eaten raw or cooked. Bulrush pollen is eaten as flour in bread, mush or pancakes. Later in the season, the seeds can be beaten off into baskets or pails, ground into a similar meal and used as flour. The large rhizomes are eaten raw or cooked; sometimes they were dried in the sun, then pounded into a kind of flour. Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani (synonym: Scirpus validus) , a similar species, has as much as 8% sugar and 5.5% starch in rhizomes, but less than 1% protein (Harrington 1972). The rhizome (underground stem) is used for the black element in basket design. Rhizomes are obtained by digging around the plant and following them out from the parent plant. Often the green stalks are cut, to make the rooting area more accessible. Bulrushes are called black root by Pomo basket weavers in California; the cream-colored rhizome is dyed black for basketry designs. The rhizomes are soaked from 3 to 6 months with acorns and a piece of iron, ashes or walnut husks until a dark brown to black color is obtained. Rhizomes are then stored in coils to dry, then woven into coiled baskets. Only about the thickness of a toothpick, the split rhizomes are both flexible and strong. Tule houses were common throughout many parts of California; the overlapping tule matters were well-insulated and rain-proof. Willow poles, arched and anchored into the ground and tied with cordage or bark formed the framework. The walls are thatched with mats of tule or cattail and secured to the frame. In Nevada, tules and willows were bound together in a sort of crude weaving for "Kani", the Paiute name for summerhouse. Tules and cattails were used as insulating thatch for structures matting, bedding, and roofing materials. As thatching material, these bulrushes were spread out in bundles, tied together, then secured in place with poles. Alfred Brousseau © Brother Eric Vogel, St. Mary’s College @ CalPhotos Several California Indian tribes make canoes of tule stems bound together with vines from wild grape. Groups located near the California coast, on mud flats and in marshes, used tule to make large round mud-shoes for their feet so they could walk without sinking. They also make dwellings of tule. Shredded tule was used for baby diapers, bedding, and menstrual padding. Women made skirts from tule. During inclement weather, men wore shredded tule capes, which tied around the neck and was belted at the waist. Duck decoys were made of tule. Other Uses: Streambank stabilization, wetland restoration, wildlife food and shelter, edible (young shoots, pollen, seeds, rhizomes), basketry, houses, roofing material, matting, bedding, canoes. These native plants are especially good for stabilizing or restoring disturbed or degraded (including logged or burned) areas, for erosion and slope control, and for wildlife food and cover. Bulrushes may be less suitable for general garden use. Wildlife: The seeds, being less hairy and larger than cattail, are one of the most important and commonly used foods of ducks and of certain marshbirds and shorebirds (Martin et al. 1951). Bulrushes provide choice food for wetland birds: American wigeon, bufflehead, mallard, pintail, shoveler, blue-winged teal, cinnamon teal, greater scaup, lesser scaup, avocet, marbled godwit, clapper rail, Virginia rail, sora rail, long-billed dowitcher, and tricolored blackbird. Canada geese and white-fronted geese prefer the shoots and roots. The stems provide nesting habitat for blackbirds and marsh wrens. Fresh emergent wetlands are among the most productive wildlife habitats in California. They provide food, cover, and water for more than 160 species of birds and numerous mammals, reptiles and amphibians. The endangered Santa Cruz long-toed salamander and rare giant garter snake use these wetlands as primary habitat. The endangered Aleutian Canada goose, bald eagle, and peregrine falcon use these wetlands for feeding and roosting. Muskrats have evolved with wetland ecosystems and form a valuable component of healthy functioning wetland communities. Muskrats use emergent wetland vegetation for hut construction and for food. Typically, an area of open water is created around the huts. Areas eaten out by muskrat increase wetland diversity by providing opportunities for aquatic vegetation to become established in the open water and the huts provide a substrate for shrubs and other plant species. Muskrats opening up the dense stands of emergent vegetation also create habitat for other species. Both beaver and muskrats often improve wetland habitat.

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status and wetland indicator values.

Description

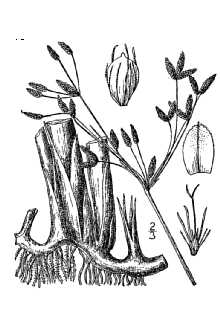

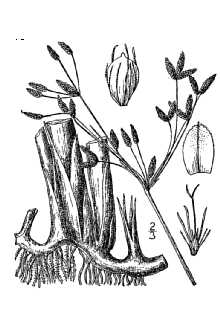

General: Sedge Family (Cyperaceae). Hardstem bulrush, a deciduous herbaceous plant, is distinguished by their long cylindric stems from 5 to 8 feet tall. The shoots senesce in the winter. The leaves are slender, v-shaped blades that are sheathed around the long stem. The flowers are arranged in a spikelet and resemble orange-brown scales. Hardstem bulrush has a tight panicle with 3 to many spikelets, and the flower bracts are prominently spotted. Bulrushes have clonal growth, with stout rootstocks and long, thick, brown rhizomes (underground stems).

Distribution

For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Bulrushes are often dominant emergent vegetation found in marshes and wetlands throughout temperate North America. Hardstem bulrush occurs across temperate North America to British Columbia and east to the Atlantic coast (Hickman 1993).

Establishment

Schoenoplectus species may be planted from bare rootstock or seedlings from container stalk or directly seeded into the soil, Germination problems have been reported in the literature for S, acutus, Consequently, live plant collections of this species are recommended, Bare rootstock or seedlings are preferred re-vegetation methods where there is moving water, Live Plant Collections: No more than 1/4 of the plants in an area should be collected, If no more than 0,09 m2 (1 ft2) should be removed from a 0,4 m2 (4 ft2) area, the plants will grow back into the hole in one good growing season, A depth of 15 cm (6 in) is sufficiently deep for digging plugs, This will leave enough plants and rhizomes to grow back during the growing season, Donor plants that are drought-stressed tend to have higher revegetation success, Live transplants should be planted as soon as possible in moist (not flooded or anoxic) soils, Plants should be transported and stored in a cool location prior to planting, Plugs may be split into smaller units, generally no smaller than 6 x 6 cm (2,4 x 2,4 in), with healthy rhizomes and tops, The important factor in live plant collections is to be sure to include a growing bud in either plugs or rhizomes, Weeds in the plugs should be removed by hand, Soil can either be left on the roots of harvested material or removed, For ease in transport, soil may be washed gently from roots, The roots should always remain moist or in water until planted, Clip leaves and stems from 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 inches); this allows the plant to allocate more energy into root production, Plant approximately 1 meter apart, Plants should be planted closer together if the site has fine soils such as clay or silt, steep slopes, or prolonged inundation, Don't flood plants right away, or the seedlings will experience high mortality, If possible, get the roots started before flooding the soils, Ideally, plants should be planted in late fall just after the first rains (usually late October to November), This enables plant root systems to become established before heavy flooding and winter dormancy occurs, Survival is highest when plants are dormant and soils are moist, Fertilization is very helpful for plant growth and reproduction, Many more seeds are produced with moderate fertilization, Seed Collections: Select seed collection sites where continuous stands with few intermixed species can easily be found, At each collection location, obtain permission for seed collection, • Seed is harvested by taking hand clippers and cutting the stem off below the seed heads or stripping the seed heads off the stalk, Hardstem bulrush plants tend to hold the seed for a long period of time after seeds are mature, so harvesting time is more flexible, • Less than 1/2 hour is required to make a decent collection of 1 to 2 cups of seed, The ease of collection is affected by water depth, • Collect and store seeds in brown paper bags or burlap bags, Seeds are then dried in these bags, • Seeds and seed heads need to be cleaned in a seed cleaner like a Crippen Cleaner, • Plant cleaned seed in fall, Plant in a clean, weed-free, moist seed bed, Flooded or ponded soils will significantly increase seedling mortality, • Broadcast seed and roll in or rake 1/4" to 1/2" from the soil surface, • Some seed may be lost due to scour or flooding, Recommended seed density is unknown at this time, Seed germination in greenhouse: • Clean seed - blow out light seed, To grow seeds, plant in greenhouse in 1" x 1" x 2" pots, 1/4" under the soil surface, Keep soil surface moist, Put in temperature of 100 degrees F (plus or minus 5 degrees), Seeds begin to germinate after a couple weeks in warm temperatures, • Plants are ready in 100 - 120 days to come out as plugs, By planting seeds in August, plugs are ready to plant in soil by November, These plants are very small; growing plants to a larger size will result in increased revegetation success, • In one study, greenhouse propagated transplants of hardstem bulrush appeared more vigorous than wild selected plants (Hoag et al, 1995), However, there were no significant differences in height or shoot density (spread) between greenhouse propagated and wild transplants, Wild collected transplants had a higher percentage of shoots flower and set seed, Greenhouse propagated transplants produced more above ground biomass (were more robust), , Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Tule.

Management

Hydrology is the most important factor in determining wetland type, revegetation, success, and wetland function and value. Changes in water levels influence species composition, structure, and distribution of plant communities. Water management is absolutely critical during plant establishment, and remains crucial through the life of the wetland for proper community management. Traditional Resource Management: The plant must grow in coarse-textured soil free of gravel, clay and silt for the roots to be of the quality necessary for basket weaving. Plants are tended by gathering and reducing the density between plants for longer rhizome production. Sustainable harvesting of plants occurs through limiting harvest in any given area. Fire is used to manage tule wetlands to remove old stems and restore open water to the wetland. This stimulates growth of new shoots from rhizomes and provides a bare soil substrate for seed germination. Many Native Americans feel the use of herbicides is inappropriate in traditional gathering sites. Bulrush is densely rhizomatous with abundant seed production. In most cases, it will out-compete other species within the wetland area of the site, eliminating the need for manual or chemical control of invasive species. Heavy grazing will eliminate Schoenoplectus species as well as other native species. Cultivars, Improved and Selected Materials (and area of origin) This species is readily available from most nurseries. Contact your local Natural Resources

Conservation

Service (formerly Soil Conservation Service) office for more information. Look in the phone book under ”United States Government.” The Natural Resources Conservation Service will be listed under the subheading “Department of Agriculture.”

References

Clarke, C.B. 1977. Edible and useful plants of California. University of California Press. 280 pp. Dahl, T.E. & C.E. Johnson 1991. Status and trends of wetlands in the coterminous United States, mid-1970s to mid-1980s. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, USDI, Washington, D.C. 28 pp. Harrrington, H.D. 1972. Western edible wild plants. The University of New Mexico Press. Albuquerque, New Mexico. 156 pp. Hickman, J.C. (ed.) 1993. The Jepson manual: Higher plants of California. University of California Press. 1399 pp. Hoag, J.C. & M.E. Sellers (April) 1995. Use of greenhouse propagated wetland plants versus live transplants to vegetate constructed or created wetlands. Riparian/Wetland Project Information Series No. 7. USDA, NRCS, Plant Materials Center, Aberdeen, Idaho. 6 pp. Martin, A.C., H.S. Zim, & A.L. Nelson 1951. American wildlife and plants: A guide to wildlife food habits. Dover Publications, Inc. New York, New York. 500 pp. Murphy, E.V.A. no date. Indian uses of native plants. Mendocino County Historical Society. 81 pp. Roos-Collins, M. 1990. The flavors of home: A guide to wild edible plants of the San Francisco Bay area. Heyday Books, Berkeley, California. 224 pp. Tiner, R.W. 1984. Wetlands of the United States: Current status and recent trends. USDI, FWS, National Wetlands Inventory, Washington, D.C. 58 pp. Timbrook, J. (June) 1997. California Indian Basketweavers Association Newsletter.