Sweetbay

Scientific Name: Magnolia virginiana L.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | MAVI2 |

| Group | Dicot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | ShrubTree, |

| Native Locations | MAVI2 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Common Names: sweetbay magnolia; laurel magnolia; swamp magnolia; small magnolia; swamp-bay; white-bay Scientific Names: Magnolia virginiana L. var. australis Sarg.; Magnolia virginiana L. var. parva Ashe

Description

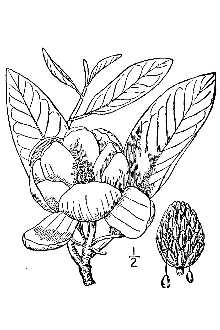

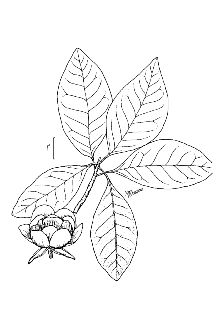

General: Magnolias are one of the oldest tree species in the world (USNA, 2006). Sweetbay is a woody, flowering, native tree that can grow up to 60 ft (grows only to 20–40 ft in the North) on multiple gray and smooth stems (Dirr, 1998; Gilman and Watson, 2014). It may be deciduous, semi-evergreen, or evergreen; and will be deciduous in its furthest northern extent. It grows similar to a shrub, with a short, open habit. It can live over 50 years. It has slender, hairy twigs, and the gray or light brown bark has scales that are pressed together. The bark is aromatic when crushed. Sweetbay is similar in appearance to southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), but it has a smaller circumference and shorter height than the latter. The 4–6 in (10–15 cm) long, 1–3 in (3–8 cm) wide leaves are simple, alternate, oblong, toothless, slightly leathery, with a wedge-shaped base and bluntly point apex. Like southern magnolia, the leaves are lustrous above and pubescent below, however sweetbay is silvery below, while southern magnolia has a rusty red pubescence (tomentum). The petiole is approximately ½ in long (Dirr, 1998). In late spring (May–June) it produces 2–3 in (5–8 cm) wide fragrant white, 9–12 spoon-shaped petaled, monoecious flowers (having male and female reproductive organs on same plant) on slender, smooth stalks. The flowers are pollinated by beetles, and open and close in a 2-day flowering cycle, alternating between a female and male pollination phase. These separate phases prevent the flower from self-pollinating, however, separate flowers on the same plant may cross-pollinate (Losada, 2014). The flowers are reported to produce a lemon scent and when the flowers close they generate heat that is beneficial to the beetles. (Bir, 1992; Losada, 2014). The fruit is an aggregate of dry, cylindrical, hairy, 2 in long (5 cm) carpels. Each follicle contains one 1/4 in (0.6 cm) long bright, oval red seed. The seed remains attached to the open pod by a thin, elastic thread. Distribution: Magnolias once made up a large part of North Temperate forest trees before the last glacial period (Maisenhelder, 1970). Sweetbay grows along the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains from Massachusetts south to Florida, west to Texas, and north to Tennessee. Sweetbay can be grown in USDA hardiness zone 5b–9 but can also be grown in lower Midwestern states such as Ohio and Indiana (Dirr, 1998). For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Sweetbay extends farther north than southern magnolia and it is designated as a USDA facultative wetland plant which means it usually occurs in wetlands. It will be found in wet, sandy, acidic soils along streams, swamps, and flatwoods (Elias, 1980). It occurs in pine and hardwood forest, flatwoods, and floodplains (Gucker, 2008). It often grows in the sweetbay/swamp tupelo/red maple forest complex and is associated with black, water, and swamp tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica, N. aquatica, N. biflora), sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), water and willow oaks (Quercus nigra, Q. phellos), white and green ash (Fraxinus americana, F. pennsylvanica), black willow (Salix nigra), and red maple (Acer rubrum) (Maisenhelder, 1970). It also dominant in bay forests with redbay (Persea borbonia) and loblolly-bay (Gordonia lasianthus) (Gucker, 2008). The soils in these habitats can be organic, acidic, sandy, saturated, nutrient-poor, peaty, or mucky. The soils can be Ultisols, Spodosols, and Coastal Plain Histosols (Priester, 2004). It grows larger in the Southeastern US where soils are richer and wetter (Elias, 1980). It is considered a climax species in many forest communities.

Adaptation

Magnolia spp. are native to Southeast Asia, eastern North America, South and Central America, and the Caribbean (Knox et al. 2013). Under natural conditions, sweetbay seedlings grow in shady to partly-shady hardwood or Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Guide coniferous forest understories. Sweetbay is different from other magnolias in that it can tolerate saturated and flooded soils as well as droughty conditions. It has been shown to survive flooding and severe drought without significant loss of root mass (Gilman and Watson, 2014; Nash and Graves, 1993). It is adapted to lower elevations less than 61 m (200ft) above sea level (Priester, 2004). It grows best in warm climates and acid soils, and is deciduous north of USDA Hardiness Zone 8 and may exhibit some winter damage in the northern part of USDA Hardiness Zone 5 (Dirr, 1998). Sweetbay is resistant to fire and can recover from top-kill due to fire, resprouting from root crowns, roots, and lignotubers (Gucker, 2008; Priester, 2004).

Uses

Timber/wood: Sweetbay does not have a significant value as a timber source, however like southern magnolia, it is used for furniture, cabinets, paneling, veneer, boxes, and crates (Hodges et al., 2010). It is straight-grained, can be easily worked, and takes finishes well (Elias, 1980). Ornamental/landscaping: Sweetbay is valued for its beauty, open form, attractive leaves, and its fragrant flowers (Hodges et al., 2010; Losada, 2012). It works well in a shrub border or as a single specimen and can be planted next to buildings or in situations with restricted space due to its horizontal crown (Gilman and Watson, 2014). It would be a good choice for rain gardens because it can tolerate saturated soils (Feather, 2013). Currently, it is not as popular as southern magnolia for use in urban settings but has potential for greater use (Gilman and Watson, 2014). Wildlife: Magnolia seed ripens in mid-Autumn and is eaten and spread by songbirds, wild turkey, quail, and mammals such as gray squirrels and white-footed mice. Seeds are high in fat and are a good energy source for migratory birds (USNA, 2006). They are eaten by eastern kingbirds, towhees, mockingbirds, northern flickers, robins, wood thrushes, blue-jays, and red-eyed vireos (Arnold Arboretum, 2011; Feather, 2013). Sweetbay is also an important plant for attracting hummingbirds (KCPD, 2007). Pollinators, especially beetles, are attracted to the pollen that is high in protein. It is a host plant for tiger swallowtail butterfly, palamedes swallowtail, spicebush swallowtail, and sweetbay silkmoth (Nitao et al., 1992; Gilman, 2015; NPIN, 2014). Deer and cattle often browse the leaves. The leaves can contain up to 10% crude protein content and can account for 25% of a cattle’s browse in winter (Hodges et al., 2010; Priester, 2004).

Ethnobotany

William Bartram (1739–1823) often wrote about sweetbay in the Southeast due to its natural beauty and importance to indigenous tribes (Austin, 2004), The leaves were used as a spice in gravies and tea was made from the leaves and/or bark (Fern, 2010), It was used by physicians in the 18th century to treat diarrhea, cough, and fever, used by the Rappahannock in Virginia as a stimulant, and the Choctaw and Houma used it as a decoction to treat colds (Austin, 2004), It was also used to treat rheumatism, gout, malaria, and was even inhaled as a mild hallucinogen (Fern, 2010; Speck et al,, 1942; Grandtner, 2005), , Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Sweetbay.

Status

Weedy or Invasive: There are no known problems with magnolias becoming weedy and there is no indication that sweetbay seed persists in the seed bank (Gucker, 2008). Please consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding its status and use. Please consult the PLANTS Web site (http://plants.usda.gov/) and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Planting Guidelines

Magnolias are moderately fast-growing trees that are easy to grow. Sweetbay may be propagated through bare root, stem cuttings, and grafts. It can be grown in containers and transplanted into the field in late winter/early spring with a mulch to moderate soil temperature and moisture (USNA, 2006). Seed can be collected in fall, soaked in water and baking soda for several days (to prevent fermentation), de-pulped, and stored for 3 months at 45°F for the requisite period of cold-stratification (MFC, 2007). Afterwards, it can be directly planted in a well-prepared seedbed in early spring. In natural forest communities sweetbay seedlings have highest survival rates when planted in large openings that are not flooded for long periods (Priester, 2004).

Management

Container-grown plants should be transplanted in spring or fall, mulched, fertilized at planting, and well-watered. Sweetbay seedlings have greater success when grown in part-shade for the first year of establishment (Priester, 2004). Applying ½ lb of 10-10-10 fertilizer at the base of the tree in March, May, and July during the first year of establishment will accelerate growth (Wade, 2012). Avoid fertilizing the tree during its slowest time of growth in fall and winter. Continued watering and mulching is required for successful establishment, and many projects with Magnolia spp. have failed due to desiccation (MFC, 2007). Sweetbay has a natural conical form and should be pruned to this shape. It may grow from several trunks, so if a single trunk in desired, prune the tree around a central leader. When sweetbay is pruned in more northern latitudes, it can “fill-out” and be more shrub-like in appearance. Plants may be coppiced (Hodges et al., 2010). Fallen leaves create a persistent residue and can be raked under the tree and used as mulch. If there is evidence of leaf spot on the fallen leaves, those leaves should be raked up and disposed (Gilman and Watson, 1994). In natural

Pests and Potential Problems

Magnolias do not tend to attract pests, however when outbreaks occur, they may result in significant economic or aesthetic loss (Knox et al. 2013). There are some reports of tulip-poplar weevil damage and leaf spots on young leaves and the magnolia borer can girdle the trunk of young nursery stock (Dirr, 1998; Gilman and Watson, 1994). Magnolia serpentine leafminer moth damage can effect plants throughout northeastern states (Knox et al., 2013) and the plant may exhibit chlorosis in Midwest calcareous soils (Dirr, 1998). Twigs and leaves may occasionally be heavily infested with scales that will not harm the growth of the plant but may negatively affect its appearance and it can be infected with verticillium wilt (Gilman and Watson, 1994; Gilman and Watson, 2014). Priester (2004) reports that sweetbay is susceptible to fungal infections of Mycosphaerella milleri (on overwintered leaves), M. glauca (causes circular leaf spots on attached leaves), and Sclerotinia gracilipes (rots flower petals). Unlike the southern magnolia, sweetbay is resistant to Japanese beetle herbivory (Held, 2004). Despite these potential problems, Magnolia spp. contain antimicrobial, insecticidal, and nematicidal properties that help to reduce potential threats from pests and diseases (Knox et al., 2013).

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

Native sweetbay populations tend to be rare at the periphery of its range, and are considered endangered in New York and Massachusetts, and threatened in Pennsylvania and Tennessee (Young, 2013; NHESP, 2010).

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Magnolias reproduce sexually and are often pollinated by beetles. There is wide variation in bloom times and flower set between cultivars. Magnolias can begin producing seed in open areas after 6 years of growth and after 10 years under normal conditions; producing abundant seed crops every year after (Gucker, 2008). Under forested conditions, the initiation of seed production is delayed until approximately 10–25 years, and in some northernmost populations only 33% of the population could produce seed (Maisenhelder, 1970; Gucker, 2008). Sweet bay is propagated through cuttings or by seed. Seeds require at least 2–3 months of cold stratification at 32–41°F and seed germination rates are 50–75% and up to 93% (Dirr, 1998; Maisenhelder, 1970; Gucker, 2008). Generally, germination rates will increase when the duration of cold stratification is increased. Germination may begin three weeks after planting. There is approximately 7,530 seeds/lb (Priester, 2004). Seed dispersal in natural communities may occur through birds, mammals, heavy rains, and winds (Maisenhelder, 1970). Cuttings taken from softwood material of young trees can be treated with root-promoting hormones and should be rooted in a well-drained sand or perlite (Dirr, 1998). They may also grow though root sprouts (Gucker, 2008). Sweetbay is prolific at sprouting after cutting or stem damage, through root sprouts, or when branches bend to the ground; and it may regenerate as far as 10 ft from the parent plant (Gucker, 2008). Young seedlings do not grow well when inundated for long periods but may grow 12–24 in (30–61 cm) within the first year (Gucker, 2008). Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Approximately half of the 80 species of magnolia native to the eastern US and Southeast Asia are in cultivation (USNA, 2006). Sweetbay has been grown in the horticulture trade in the US since the 17th century, so it is often difficult to distinguish natural populations from escaped ornamental plants (Young, 2013). There are many cultivars of sweetbay developed with different heights, growth habits, bloom times, bloom abundance, and cold tolerance. Generally, when planted in northern latitudes it will be shorter and more shrub-like. The more cold-tolerant cultivars are ‘Milton’, ‘Moonglow’, ‘Ravenswood’, and ‘Henry Hicks’. The cultivar ‘Tensaw’ is a hardy, short, dwarf-leaf, cold-tolerant variety for use in the northernmost extent of its range. Its parent tree is from Ohio and is less shrubby than many available varieties. Magnolia virginiana var. australis is a variety better adapted for the southern US and is more tree-like in form. Consult with your local land grant university, local extension or local USDA NRCS office for recommendations on adapted cultivars for use in your area.

Literature Cited

Arnold Arboretum. 2011. Fruits of autumn. Arnold arboretum seasonal guide. The Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. Boston, MA. Austin, D.F. 2004. Florida ethnobotany. CRC Press. Boca Raton, FL. Bir, R. E. 1992. Growing and propagating showy native woody plants. Univ. of N. Carol. Press. Chapel Hill, NC. Dirr, M.A. 1998. Magnolia virginiana. Stipes Publishing. Champaign, Illinois. Elias, T.S. 1980. The complete trees of North America. Times Mirror Magazines, Inc. New York, NY. Feather, 2013. Tree of the month–sweetbay magnolia: magnolia virginiana. College of Ag. Sci. Penn State Ext. University Park, PA. Fern, K. 2010. Magnolia virginiana. Plants for a Future (PFAF). UK. Gilman, E.F. 2015. Magnolia virginiana, sweetbay magnolia. Landscape Plants. UF IFAS Extension. Univ. of FL. Gainesville, FL. Gilman, E.F., and D.G. Watson. 1994. Magnolia grandiflora: southern magnolia. Pub. #ST-371. USDA US Forest Service Factsheet. UF IFAS Extension. Univ. of FL. Gainesville, FL. http://hort.ifas.ufl.edu/database/documents/pdf/tree_fact_sheets/maggraa.pdf (accessed 19 Feb. 2015). Gilman, E.F. and D.G. Watson. 2014. Magnolia virginiana: sweetbay magnolia. UF IFAS Extension. Univ. of FL. Gainesville, FL. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/ST/ST38400.pdf (accessed 03 Mar. 2015). Grandtner, M.M. 2005. Elsevier’s dictionary of trees: North America vol. 1. Elsevier B.V. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Gucker, C.L. 2008. Magnolia virginiana.

Fire Effects

Information System. Rocky Mountain Research Station. USDA Forest Service. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ (accessed 03 Mar. 2015). Held, D.W. 2004. Relative susceptibility of woody landscape plants to Japanese beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). J. Arboric. 30(6):328–335. Hodges, J.D., D.L. Evans, L.W. Garnett, A. Londo, and L. McReynolds. 2010. Mississippi trees. Miss. State Univ. Ext. Service. Miss. Forestry Commission. Jackson, Mississippi. http://www.fwrc.msstate.edu/pubs/ms_trees.pdf (accessed 17 Feb. 2015). KCPD (Knox County Park District). 2007. Hummingbird plants. Knox County Park District. Mt. Vernon, OH. http://www.knoxcountyparks.org/pdfs/hummingbird%20plants%20fact%20sheet.pdf (accessed 05 Mar. 2015). Knox, G.W., W.E. Klingeman III, A. Fulcher, M. Paret. 2013. Insect and nematode pests of Magnolia species in the southeastern United States. Issue 94. Univ. of Tenn. Knoxville, TN. http://plantsciences.utk.edu/pdf/Knox_etal-Insects_Nematodes_Magnolia-94_2013.pdf (accessed 27 Feb. 2015). Losada, J.M. 2014. Magnolia virginiana: ephemeral courting for millions of years. Arnoldia 71/3. Arnold Arboretum. Boston, MA. http://www.arboretum.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014-71-3-magnolia-virginiana-ephemeral-courting-for-millions-of-years.pdf Maisenhelder, L.C. 1970. Magnolia: (Magnolia grandiflora and Magnolia virginiana). American Woods FS–245. USDA Forest Service. Mississippi Forest Commission (MFC). 2007. The southern magnolia. MFC Publication #38. Jackson, MS. Nash, L.J., and W.R.Graves.1993. Drought and flood stress effects on plant development and leaf water relations of five taxa of trees native to bottomland habitats. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 118(6):845–850. NHESP (National Heritage Endangered Species Program). 2010. Sweet bay, Magnolia virginiana. Mass. Div. Fish. Wild. Westborough, MA. http://www.mass.gov/eea/docs/dfg/nhesp/species-and-conservation/nhfacts/magnolia-virginiana.pdf (accessed 05 Feb. 2015). Nitao, J.K., K.S. Johnson, J.M. Scriber, M.G. Nair. 1992. Magnolia virginiana neolignan compounds as chemical barriers to swallowtail butterfly host use. J. Chem. Ecol. 18(9):1661–1671. NPIN (Native Plant Information Network). 2014. Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. The Univ. of Texas at Austin. Priester, D.S. 2004. Magnolia virginiana: sweetbay. p. 888–896. In Agriculture Handbook 654. Silvics Manual Volume 2: Hardwoods. USDA-Forest Service. http://www.na.fs.fed.us/spfo/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_2/silvics_v2.pdf (accessed 06 Mar. 2015). Speck, F.G., R.B. Hassrick, and E.S. Carpenter. 1942. Rappahannock herbals, folk-lore, and science of cures. p. 28. In Proc. Del. County Inst. of Sci. 10:7–55. USNA (United States National Arboretum). 2006. Magnolia questions and answers. National Arboretum. Washington, D.C. Wade, G.L. 2012. Growing southern magnolia. Circular 974. The Univ. of GA Coop. Ext. Athens, GA. Young, S. M. 2013. Sweetbay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana). New York Natural Heritage Program (NYNHP) Conservation Guide. Abany, NY. http://acris.nynhp.org/report.php?id=9188 (accessed 05 Feb. 2015) Citation Sheahan, C.M. 2015. Plant guide for sweetbay (Magnolia virginiana). USDA-Natural Resources

Conservation

Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May, NJ. Published 03/2015 Edited: May2015 rg For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or Conservation District at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/ and visit the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov/ or the Plant Materials Program Web site: http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov. PLANTS is not responsible for the content or availability of other Web sites.

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | 17 |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | Low |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | None |

| Cold Stratification Required | Yes |

| Drought Tolerance | None |

| Fertility Requirement | Medium |

| Fire Tolerance | None |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 180 |

| Hedge Tolerance | Medium |

| Moisture Use | High |

| pH, Maximum | 6.9 |

| pH, Minimum | 5.0 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Maxim | 800 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Minim | 300 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 80 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 40 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 30 |

| Salinity Tolerance | None |

| Shade Tolerance | Intermediate |

Morphology/Physiology

| Bloat | None |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | None |

| Resprout Ability | Yes |

| Shape and Orientation | Climbing |

| Active Growth Period | Spring and Summer |

| C:N Ratio | High |

| Coppice Potential | Yes |

| Fall Conspicuous | No |

| Fire Resistant | Yes |

| Flower Color | White |

| Flower Conspicuous | Yes |

| Foliage Color | Dark Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Moderate |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Moderate |

| Foliage Texture | Medium |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | Yes |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Lifespan | Moderate |

| Leaf Retention | Yes |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Height, Mature (feet) | 60.0 |

| Height at 20 Years, Maximum (fee | 40 |

| Growth Rate | Moderate |

| Growth Form | Single Stem |

| Fruit/Seed Color | Black |

Reproduction

| Vegetative Spread Rate | None |

|---|---|

| Small Grain | No |

| Seedling Vigor | Low |

| Seed Spread Rate | Slow |

| Fruit/Seed Period End | Winter |

| Seed per Pound | 7530 |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | No |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Seed | Yes |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

| Propagated by Container | Yes |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | Yes |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | No |

| Fruit/Seed Period Begin | Summer |

| Fruit/Seed Abundance | Medium |

| Commercial Availability | Routinely Available |

| Bloom Period | Summer |

| Propagated by Cuttings | Yes |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | Yes |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | Yes |

| Protein Potential | Medium |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | No |

| Palatable Browse Animal | High |

| Nursery Stock Product | Yes |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | No |

| Fuelwood Product | Low |

| Fodder Product | No |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | No |