Giant Cane

Scientific Name: Arundinaria gigantea (Walter) Muhl.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | ARGI |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | GraminoidShrub, Subshrub, |

| Native Locations | ARGI |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Cane, Fishing-pole Cane, Mutton Grass, Rivercane, Swampcane, Switchcane, Wild Bamboo

Uses

Cultural: Dense stands of cane, known as canebrakes, have been likened to a “supermarket” offering material for many purposes (Figure 2) (Kniffen et al. 1987). Cane provided the Cherokee with material for fuel and candles and the coarse, hollow stems were made into hair ornaments, game sticks, musical instruments, toys, weapons, and tools (Hill 1997; Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975). The Houma, Koasati, Cherokee, Chitimacha, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole made the stems into arrow shafts, blowguns (Figure 3) and darts (Figure 4) for hunting squirrels, rabbits, and various birds (Bushnell 1909; Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975; Speck 1941; Kniffen et al. 1987). Young Cherokee boys used giant cane blowguns armed with darts to protect ripening cornfields from scavenging birds and small mammals (Fogelson 2004). The Choctaw used the butt end of a cane, where the outside skin was thick, as a knife to cut meat, or as a weapon (Swanton 1931). Tribes of Louisiana made flutes, duck calls, and whistles out of cane (Kniffen et al. 1987). Cane is best harvested in the fall or winter (October to February) for blow guns and flutes, and plant stems, known as culms, are selected from mature, hardened off plants with larger diameters. Figure 2. Stand of giant cane (Arundinaria gigantea). Photo taken on tribal lands of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, taken by Timothy Oakes, 2011. Figure 3. A Choctaw man demonstrating how a blowgun is positioned for shooting. The blowgun is about 7 feet in length and made of a single piece of giant cane. Photo by David I. Bushnell, Jr., 1909. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, National Anthropological Archives. Figure 4. Chitimacha blowgun darts of fire-treated split cane. Courtesy of the Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution E76807. Young shoots were cooked as a potherb and ripe seeds were gathered in the summer or fall and ground into flour for food (Morton 1963; Hitchcock and Chase 1951). Flint (1828) says of a subspecies of giant cane, Arundinaria gigantea ssp. macrosperma: “It produces an abundant crop of seed with heads like those of broom corn. The seeds are farinaceous and are said to be not much inferior to wheat, for which the Indians and occasionally the first settlers substituted it.” Giant cane also has medicinal properties. Both the Houma and the Seminole made a decoction of the roots: the Houma used it to stimulate the kidneys and renew strength, and the Seminole used it as a cathartic (Speck 1941; Sturtevant 1955 cited in Moerman 1998). Cane was important for construction of indigenous dwellings, as well as the creation of the mats and baskets that formed a large part of household furnishings (Galloway and Kidwell 2004). Entire canes were used for Choctaw beds, house roofs, and walls and they made pallets of whole canes on which to spread hides (Swanton 1931). The Cherokee constructed dwellings with cane webbing, plastered with mud (Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975). The Pascagoula and the Biloxi made temples of cane as a resting place for their chiefs and the Choctaw placed their dead in giant cane hampers (Brain et al. 2004; Swanton 1931). Woven mats of cane covered ceremonial grounds, seats, floors, and walls, and roofs were thatched with it (Hill 1997; Swanton 1946). The Natchez made cane mats with red and black designs, that were 4 ft. wide and 6 ft. long (Swanton 1946). The houses of Seminole chiefs were covered with checkered mats of canes dyed different colors (Bartram 1996). The Houma, Biloxi, Chitimacha, Tunica, and Koasati used cane for the making of rafts, bedding, roofing, and floor and wall coverings (Kniffen et al. 1987). Archeological excavations have revealed that giant cane was laid down in criss-crossed layers to mantle the sloping sides of the bases of certain mounds such as the Great Mound in east central Louisiana (Neuman 2006). One of the most important uses of giant cane stems today and in ancient times is for forming the rich natural yellow color in the baskets of the Alabama Coushatta, Biloxi-Tunica, Caddo, Cherokee, Chitimacha, Choctaw, Creek, Koasati, Seminole and other tribes (Figures 5 and 6) (Brain et al. 2004; Bushnell 1909; Gettys 1979; Gregory Jr. 2004; Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975; Swanton 1942). Figure 5. Haylaema, Choctaw, with a carrying basket made of giant cane. Photograph by David I. Bushnell, Jr., St. Tammany Parish, La., 1909. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, National Anthropological Archives, 1102.b.22. Pack, berry, sifting, chafing, winnowing, catch, storage, gift, and cooking baskets all carry stems of this grass (Duggan and Riggs 1991; Gettys 1979; 2003). Venison, buffalo meat, pumpkins, hominy and boiled beans were presented in serving vessels made of giant cane. Choctaw mothers lay their children in cradles of cane (Swanton 1946). Cherokee fish traps were made of giant cane (Leftwich 1970). As non-Indians began to settle in the Southeastern United States, weavers from various tribes began to trade their baskets with the new settlers for items that they needed such as flour, coffee, sugar, ribbons, and fabric. Thus, cane basketry became part of the exchange-based colonial economy (Duggan and Riggs 1991; Lee 2002; 2006). Matting and basketry technologies that use giant cane have been found in archaeological sites in Louisiana dating back to at least 2300 B.C. (Neuman 2006). Figure 6. Zula Chitto, Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, weaving a basket of giant cane. Photo by Bradley Isaac, Jr., Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Giant cane was broken or cut to its base with a shell or bone knife or other lithic devices, and in later times other tools such as a sugar cane knife were used. Today pruning shears are frequently employed (Neuman 2006; Hill 1997; 2002). The Jena Band of Choctaw look for culms at least four feet long, of a solid color, and at least five to seven years old (Lee 2002). The Eastern Band of Cherokee select large canes about the size of the thumb that are at least two years old (Leftwich 1970). Chitimacha weavers select giant cane with long lengths between the joints (Darden et al. 2006; NRCS 2002; 2004). In Choctaw basketry it was customary to collect canes in the winter, because they were too brittle in the summer (Swanton 1931). Today giant cane is harvested in every season, but fall, winter, and early spring are the preferred times for many weavers because the cane is firm, but not too hard or too soft. The cane is cut while still green, and the small foliage end is cut off and discarded. The cane is then washed in non-chlorinated water, and divided into four or eight strips of approximately equal size (Figure 7). Figure 7. Dorothy Chapman, Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, splitting giant cane into strips of approximately equal size for a basket she will make. Photo by Bradley Isaac, Jr., Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Sarah H. Hill (1997) describes the next step of preparation—the thinning of the strands: “…the weaver repeatedly inserts the knife under the cane’s outer cortex and then pulls the core back as she guides the cut with her knife. She works down the length of the stick, detaching the interior core until only the exterior of the cane remains as a thin, pliable split.” After the coarse inner fiber of the cane is scraped and discarded, the cane splints are then trimmed along each edge to make them of uniform width (Leftwich 1970). The materials must be kept damp or are re-dampened during the weaving process. If not used, the strips are bundled for storage (Kniffen et al. 1987). Historically, if stored without splitting the culms first, the Choctaw kept them in stacks covered an inch or two in water (Swanton 1931). Many kinds of plants were, and continue to be, used to dye giant cane black, red, or yellow. The Choctaw burned equal parts of the bark of the Texas red oak (Quercus texana) and water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) to a fine ash which formed the red color in their basketry (Bushnell 1909). The Cherokee dye the grass with natural dyes such as black walnut (Juglans nigra) root to obtain a black or deep brown and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) to obtain a reddish color and these materials formed designs in baskets (Speck 1920). The Jena Band of Choctaw use the berries of elderberry (Sambucus spp.) to dye the cane red and the green husks of hickory nuts or walnuts to make a black dye. The Chitimacha use curly dock (Rumex crispus) and black walnut to dye their cane baskets (Kniffen et al. 1987). Early non-Indian settlers valued the canebrakes as natural pastures for their domesticated animals (Hughes 1951). According to environmental historian Mart Stewart (2007), “Modern studies have established that cane foliage was the highest yielding native pasture in the South. It has up to eighteen percent crude protein and is rich in minerals essential for livestock health.” Livestock eagerly eat the young plants, leaves, and seeds and stands decline with overgrazing and rooting by hogs (Hitchcock and Chase 1951). Giant cane was sometimes slit and made into chair bottoms, weavers’ shuttles, and the hollow stems for inexpensive tubes (Porcher 1991). Non-Indian settlers also used the giant cane for fishing poles, weaving looms, scaffolds for drying cotton, pipe stems and pipes, splints for baskets and mats, toys, turkey-calls, and musical instruments (Marsh 1977). Giant cane is an excellent plant to stabilize stream and river banks. The roots and rhizomes link together to create an underground mesh that ties the soil and plant to the ground. The flexible culms bend in high water and resist breakage, but also act to seine floating organic matter out of the flood waters causing it to drop within the brake. It is being included in riparian buffer designs, serving as an effective plant for erosion control. Giant cane is also proving to be an effective intercept filter of sediment, pesticides, and nutrients flowing from agricultural watersheds which improves water quality (Schoonover et al. 2010). Wildlife: Canebrakes are an important ecosystem for wildlife. Historical accounts along with recent surveys identify at least 23 mammal species, 16 bird species, four reptile species and seven invertebrates that occur within canebrakes (Platt et al. 2001). A rare neotropical migrant, the Swainson’s warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii) builds its nests in dense cane thickets (Benson et al. 2009; Thomas et al. 1996). The copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix), cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus), and canebrake rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), an endangered species, live and hunt in canebrakes. The swamp rabbit (Sylvilagus aquaticus) is restricted to canebrakes along the northern border of its geographic range. White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) graze on tender cane shoots in early spring (Silberhorn 1996). Six species of butterflies are obligate bamboo specialists, including the Creole pearly eye (Enodia creola), southern pearly eye (E. portlandia), Southern swamp skipper (Poanes yehl), cobweb little skipper (Amblyscirtes aesculapius), cane little skipper (A. reversa), and yellow little skipper (A. carolina) (Scott 1986 cited in Brantley and Platt 2001). Canebrakes provide refuge and living quarters for black bears (Ursus americanus), bobcats (Lynx rufus), and cougars (Puma concolor). Squirrels (Sciurus spp.) and wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) feed on the seeds of giant cane and Carolina parakeets (Conuropsis carolinensis) and passenger pigeons (Ectopistes migratorius), both now extinct, used to feed on them (Platt and Brantley 1997).

Status

Please consult t Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Weediness

This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not properly managed. Please consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding its status and use. Weed information is also available from the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov/. Please consult the Related Web Sites on the Plant Profile for this species for further information.

Description

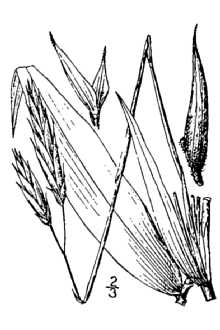

General: A cool-season member of the grass family (Poaceae), giant cane comes from the genus Arundinaria and is the only bamboo native to the United States. It has erect, perennial woody stems or culms that are two cm thick that reach up to 10 m and a diagnostic character for this genus is the presence of culm sheaths at each node of the culm (Brantley and Platt 2001; Hitchcock and Chase 1951; Hughes 1951). In parts of Alabama, historical accounts report cane growing “as high as a man on horse-back could reach with an umbrella” (Harper 1928 cited in Marsh 1977). The culm leaves are deciduous. Foliage leaves are evergreen, eight-15 cm long, and strongly cross veined (Clark and Triplett 2007). The inflorescence is a raceme or panicle that dies after fruiting or sometimes after two consecutive growing seasons (Crow and Hellquist 2000; Platt et al. 2004). In many populations the plants seldom flower, usually only every 10 to 15 years (Silberhorn 1996). Giant cane may be monocarpic, meaning that after decades of vegetative growth, it flowers once and then dies (Gagnon 2009). It has running, horizontal rhizomes that are long and slender and sometimes

Adaptation

Canebrakes need some kind of disturbance to maintain them (Meanley 1966). Giant cane is fire-adapted, sprouting rapidly from rhizomes (Taylor 2006). If only aerial portions are killed by fire or broken, new culms arise from the underground part of the old culms (Hughes 1951 cited in Marsh 1977). Canebrake vegetation is adapted to anthropogenic disturbance regimes in the form of indigenous burning and natural disturbance regimes in the form of riverine flooding, lightning fires, overstory deadening by roosting flocks of passenger pigeons in former times, and windstorms (Brantley and Platt 2001). Cane develops well with periodic flooding, but does not tolerate permanent saturation (Marsh 1977). In the past, fire maintained open Arundinaria-Ilex bog areas in the Southeast, keeping beech-maple forest from encroaching (Marsh 1977).

Establishment

Because giant cane seldom flowers, a source of seed is unpredictable. Giant cane also has naturally low seed viability and flowering stands can fail to produce seeds, limiting the availability of viable seeds for seedling production (Neal et al. 2011). Attempts to reestablish canebrakes using vegetative propagation techniques have had limited success (Cirtain 2003). In one study, Gagnon and Platt (2008b) found that giant cane seed survival and seedling establishment is improved with controlling seed-predators and herbivores, and planting seeds directly in a layer of leaf litter in moderate shade. Seed should be planted on several sites with a range of environmental conditions with multiple genetic individuals that flower in-phase (Gagnon and Platt 2008b). Another method is to grow seedlings in a greenhouse and outplant them after one year (Gagnon and Platt 2008b). Nodal sections of giant cane containing an axillary bud can be used as explants material. Giant cane can also be transplanted during the late fall to early spring. Recent transplanting work in Alabama and Mississippi indicates that winter planting (December-March) will give the greatest success in establishment (Hamlington et al. 2011). Plants at least one foot high, and with two feet long rhizomes and roots attached, can be dug and transplanted into a well-drained, fertile soil, three to six inches deep. However, water must be available for these transplants. If regular irrigation is not available, transplanting must be done in the winter months (December through the first weeks of March).The soil should have a pH level of 6.8 to 7.2 and sandy soils and areas that have peat tend to produce larger varieties of cane (Oakes 2006). Giant cane should have at least three to four hours of direct sunlight daily. Full sun exposure seems to limit top growth, but strongly enhances rhizome and root growth, allowing maximum overall growth of the canebrake (Neal et al. 2011; Russell et al. 2011). If planting giant cane on the grounds surrounding the home, keep the plants moist during the first year, but not waterlogged. After one year of establishment, apply fertilizer that contains nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium (NPK), and every other year, any type of composted manure (chicken, horse, and cow) can be substituted (Oakes 2006). Manure can be applied in late fall or early winter (Oakes 2006). Currently researchers are investigating methods of vegetative propagation in order to increase the supply of plant materials for restoration projects. M.C. Mills (2011) found that planting giant cane amongst established, clump-forming grasses such as big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) and Indiangrass (Sorgastrum nutans), may provide some environmental facilitation, while reducing direct competition because of the differing growth strategies. Paul R. Gagnon (2009) implores managers to consider fire-maintained plant assemblages within bottomland hardwood forests as part of restoration plans. Dr. Brian Baldwin (2009) at Mississippi State University has, in collaboration with EPA Region 4, NRCS-AWCC and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI), developed propagation techniques and re-established cane in the Pearl River watershed on land belonging to the Mississippi Choctaw (Jolley et al. 2009). Not only the MBCI but also other tribes have put much effort into restoring cane stands so that they can continue their traditions (Oakes 2006). Cane has been re-established on the Chitimacha Reservation in Louisiana and at Kituwha, North Carolina with the Eastern Band of Cherokee (NRCS 2002; 2004). Due to limited access to favorable habitat on tribal lands, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is working closely with local conservation groups and land managers to preserve and expand existing cane, establish new canebrakes, and secure access for Cherokee artists (D. Cozzo, pers. comm. 2011). Basketry traditions are being passed down to the youth, as part of cultural revitalization (Figure 9). Figure 9. High school student Jorree Wolfe, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, making a basket of giant cane. Photo by Beth Ross Johnson.

Management

Harvesting giant cane judiciously can be good for the plant as Sarah H. Hill (1997) explains among the Southeastern Cherokee: “Cutting cane also stimulated its regeneration by creating openings for the spread of new stems. Selective cutting of stalks for baskets is an effective way to prune stands.” Native Americans burned cane once every seven to 10 years (Campbell 1985; Hill 1997; Platt and Brantley 1997). Writing about the prairies in south central Arkansas, geologist Featherstonhaugh (1844) recorded the burning of the cane and high grass by the Indians to secure their game. Ecologists have concluded that fire will maintain and even expand canebrakes if occurring once every 10 years (DeVivo 1991; Shepherd et al. 1951, Hughes 1957). Fires set in fall, winter, or spring may improve conditions for cane and with fire exclusion, cane colonies lose vigor and are gradually replaced by woody vegetation (Hughes 1957; Platt and Brantley 1997). Paul R. Gagnon and William J. Platt (2008a) hypothesize that multiple disturbances that include fire and windstorms or other space-opening disturbances promote monotypic-stand formation in giant cane and fire spurs clonal growth in giant cane’s mature phase. As early as 1913, anthropologist Frank G. Speck recorded among the Cherokee weavers in the Great Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina that the giant cane was getting scarcer (Speck 1920). In 1979, Libby Jo Devine (1979) completed a Master’s Thesis at Georgia State University and she recorded that “a [southeastern] basketmaker will have to travel 60-100 miles for river cane, as it is becoming scarce.” Many of the floodplain forests connected with the river systems with canebrakes were converted to agricultural lands. Canebrakes also diminished with changes in hydrological regimes with dams and the creation of recreational impoundments, and overgrazing by domestic livestock (Brantley and Platt 2001; Thomas et al. 1996). Many patches of cane have stopped producing due to overcrowding of hardwoods and pines and thinning the trees 50 to 75 percent will allow cane to have less competition for growth and increase productivity (Oakes 2006). Fires, from lightning and Native Americans rejuvenated canebrakes, but after European settlement these fire regimes were altered, sometimes converting giant cane to grasslands or open savanna (Brantley and Platt 2001; Wells and Whitford 1976 cited in Platt and Brantley 1997). In the absence of enriching fire and flood, canebrakes reach maturity in about ten years. Stalks then begin to decline in vigor and gradually die. In contrast to the rapid re-growth that follows disturbance, undisturbed regeneration may take as long as several decades (Hughes 1966). Steven Platt and Christopher Brantley (1997) suggest that the best strategy for cane restoration is to manage and expand existing cane stands through a combination of thinning the overstory, periodic burning, and possibly fertilization. Hughes (1957) also recommended controlled burning as a means to renovating decadent cane stands.

Control

Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) This plant is available from native plant nurseries. Also check with your local NRCS Plant Materials Center for possible sources of existing plant materials. Research conducted on canebrakes that are flowering but not producing seed indicates that many canebrakes in some areas are composed of only one individual, or two related individuals. Giant cane is like people when it comes to producing offspring. In order for restoration projects using vegetative material or seed to be successful in the long term, restoration plants should use a mixture of genotypes (cane plants/propagules from several locations or watersheds) (Baldwin 2010).

References

Baldwin, Brian S., M. Cirtain, D.S. Horton, J. Ouellette, S. Franklin and J.E. Preece. 2009. Propagation methods for rivercane [Arundinaria gigantea L. (Walter) Muhl.]. Castanea 74(3):300-316. Baldwin, B., J. Wright, C. Perez, M. Kent-First, and N. Reichert. 2010 Rivercane (Arundinaria gigantea) flowering, but no seed production: A potential answer. Seventh Eastern Native Grass Symp. Knoxville, TN. Oct 5-8. Banks, W.H. 1953. Ethnobotany of the Cherokee Indians. Master of Science, University of Tenessee. Bartram, W. 1996. William Bartram Travels and Other Writings. Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y. Benson, T.J., N.M. Anich, J.D. Brown, and J.C. Bednarz. 2009. Swainson’s warbler nest-site selection in eastern Arkansas. The Condor 11(4):694-705. Brantley, C.G. and S.G. Platt. 2001. Canebrake conservation in the Southeastern United States. Wildlife Society Bulletin 29(4):1175-1181. Brain, J.P., G. Roth, and W.J. De Reuse. Tunica, Bioloxi, and Ofo. 2004. Pages 586-597 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 14: Southeast. R.D. Fogelson Vol. ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Bushnell, D.L., Jr. 1909. The Choctaw of Bayou Lacomb, St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, Number 48. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Campbell, J.J.N. 1985. The Land of Cane and Clover: Presettlement Vegetation in the So-called Bluegrass Region of Kentucky. Report from the Herbarium. University of Kentucky, Lexington. Cirtain, M.C. 2003. Restoration of Arundinaria gigantea (Walter) Muhl. Canebrakes Using Micropropagation. Master’s Thesis. University of Memphis, Tennessee. Clark, L.G. and J.K. Triplett. 2007. Arundinaria. Pages 17-20 in: Flora of North America vol. 24. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Poaceae, Part 1. Flora of North American Editorial Committee. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y. Crow, G.E. and C.B. Hellquist. 2000. Aquatic and Wetland Plants of Northeastern North America. Vol II: Angiosperms: Monocotyledons. A Revised and Enlarge Edition of Norman C. Fassett’s A Manual of Aquatic Plants. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. Darden, J.P., S. Darden, and M.D. Brown. 2006. In the family tradition: a conversation with Chitimacha basketmakers. Pages 29-41 in: The Work of Tribal Hands: Southeastern Indian Split Cane Basketry. D.B. Lee and H.F. Gregory (eds.). Northwestern State University Press, Natchitoches, Louisiana. Devine, L.J. 1979. Basketry in the Southeast United States. Master’s Thesis. Art Education Department. Georgia State University, Atlanta. DeVivo, J. 1991. The Indian use of fire and land clearance in the southern Appalachians. Pages 306-310 in: Fire and the Environment: Ecological and Cultural Perspectives. S.C. Nodvin and T.A. Waldrop (eds.). U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southeast For. Exp. Stn., Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-69. Duggan, B.J. and B.H. Riggs. 1991. Studies in Cherokee Basketry. Occasional Paper No. 9. Frank H. McClung Museum. The University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Farrelly, D. 1984. The Book of Bamboo. Sierra Club Books, San Francisco. Flint, 1828. Western States. (complete citation not available). Fogelson, R.D. 2004. Cherokee in the East. Pages 337-353 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 14: Southeast. R.D. Fogelson Vol. ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gagnon, P.R. 2006. Population Biology and Disturbance Ecology of a Native North American Bamboo (Arundinaria gigantea). PH.D. dissertation, Department of Biological Sciences. Louisian State University, Baton Rouge. _____. 2009. Fire in floodplain forests in the Southeastern USA: insights from disturbance ecology of native bamboo. Wetlands 29(2):520-526. Gagnon, P.R. and W.J. Platt. 2008a. Multiple disturbances accelerate clonal growth in a potentially monodominant bamboo. Ecology 89(3):612-618. _____. 2008b. Reproductive and seedling ecology of a semelparous native bamboo (Arundinaria gigantea, Poaceae). Galloway, P. and C.S. Kidwell. 2004. Choctaw in the East. Pages 499-519 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 14 Southeast. R.D. Fogelson (Vol. ed.). Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gettys, M. 1979. Basketry of the Eastern United States. Self-published. _____. 2003. Weave, Wattle & Weir: Fiber Art of the Native Southeast, September 7-October 19, 2003. Tennessee Valley Art Center. Tennessee Valley Art Association, Tuscumbia , Ala. Gregory, Jr. H.F. 2004. Survival and maintenance among Louisiana tribes. Pages 653-658 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 14: Southeast. R.D. Fogelson Vol. ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Hamel, P.B. and M.U. Chiltoskey. 1975. Cherokee Plants and their Uses—A 400 Year History. Herald Publishing, Sylva, North Carolina. Hamlington, J.A., M.D. Smith, B.S. Baldwin and C.J. Anderson. 2011. Native cane propagation and site establishment in Alabama. Natl.

Wildlife

Soc, Mtg, Waikoloa, HI, 5-10 Nov, Harper, R,M, 1928, Economic Botany of Alabama, Part 2: Catalogue of the Trees, Shrubs, and Vines of Alabama with their Economic Properties and Local Distribution, Monograph 9, Geological Survey of Alabama, University of Alabama, Hill, S,H, 1997, Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Hitchcock, A,S, and A, Chase, 1951, Manual of the Grasses of the United States, U,S,D,A, Miscellaneous Publication No, 200, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D,C, Hughes, R,H, 1951, Observations of cane (Arundinaria) flowers, seed, and seedlings in the North Carolina Coastal Plain, Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 78(2):113-121, _____, 1957, Response of cane to burning in the North Carolina coastal plain, North Carolina Agric, Exp, Stn,, Tech, Bull, 402, _____, 1966, Fire ecology of canebrakes, Pages 149-58 in: Fifth Annual Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, Florida, Jolley, R,, B, Baldwin, D,M, Neal, and G, Ervin, 2009, Restoring endangered ecosystems: Canebrakes, Symposium: Improving wildlife habitat through the effective use of plants, Wildlife Soc, 16th Ann, Conf, Monterey, CA, 20-24 Sep, Kniffen, F,B,, H,F, Gregory, and G,A, Stokes, 1987, Tribes of Louisiana from 1542 to the Present, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, Lee, D,B, 2002, Uski Taposhik Cane Basketry Traditions of the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians, Video, NSU, Louisiana Regional Folklife Program, _____, 2006, The ties that bind: cane basketry traditions among the Chitimacha and the Jena Band of Choctaw Pages 43-71 in: The Work of Tribal Hands: Southeastern Indian Split Cane Basketry, D,B, Lee and H,F, Gregory (eds,), Northwestern State University Press, Natchitoches, Louisiana, Leftwich, R,L, 1970, Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee, Cherokee Publications, Cherokee, NC, Marsh, D,L, 1977, The taxonomy and ecology of cane, Arundinaria gigantea (Walter) Muhlenburg, Ph,D, Dissertation, University of Arkansas, Little Rock, Meanley, B, 1966, Some observations on habitats of the Swianson’s warbler, Living Bird 5:151-165, Mills, M,C, 2011, Empirical studies of Arundinaria species for restoration purposes, Master’s degree thesis, Mississippi State University, Starkville, Mills, M,C,, B,S, Baldwin, and G,N, Ervin, 2011, Evaluating physiological and growth responses of Arundinaria species to inundation, Castanea 76:371-385, Moerman, D,E, 1998, Native American Ethnobotany, Timber Press, Portland, OR, Morton, J,F, 1963, Principal wild food plants of the United States excluding Alaska and Hawaii, Economic Botany 17(4):319-330, Neal, D,M,, B,S, Baldwin, G,N, Ervin, R,L, Jolley, J,N,J, Campbell, M, Cirtain, J, Seymour, and J,W, Neal, 2011, Assessment of seed storage alternatives for rivercane [Arundinaria gigantean L,(Walter) Muhl,], Unpublished data, Neuman, R,W, 2006, Split cane items in Louisiana: a view from archeology and ethnology, Pages 5-26 in: The Work of Tribal Hands: Southeastern Indian Split Cane Basketry, D,B, Lee and H,F, Gregory (eds,), Northwestern State University Press, Natchitoches, Louisiana, Noss, R,F,, E,T, LaRoe III, and J,M, Scott, 1995, Endangered Ecosystems of the United States: A Preliminary Assessment of Loss and Degradation, U,S, Department of the Interior, Washington, D,C, NRCS, 2002, Chitimacha River Cane Project Results 2001-2002, Golden Meadow Plant Materials Center, USDA NRCS, Galliano, LA, NRCS, 2004, Chitimacha River Cane Project Results 2004, Golden Meadow Plant Materials Center, USDA NRCS, Galliano, LA, Oakes, T, 2006, Native cane conservation guide: Arundinaria gigantea ssp, tecta, traditionally known as swamp cane, Pages 211-218 in: The Work of Tribal Hands: Southeastern Indian Split Cane Basketry, D,B, Lee and H,F, Gregory (eds,), Northwestern State University Press, Natchitoches, Louisiana, Platt, S,G, and C,G, Brantley, 1997, Canebrakes: an ecological and historical perspective, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Giant Cane., Castanea 62(1):8-21, Platt, S,G,, C,G, Brantley, and T,R, Rainwater, 2001, Canebrake fauna: wildlife diversity in a critically endangered ecosystem, The Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 117(1):1-19, _____, 2004, Observations of flowering cane (Arundinaria gigantea) in Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, Porcher, F,P, 1991, Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests: Medical, Economical, and Agricultural, Norman Publishing, San Francisco, Originally published in 1863 by Steam-power Press of Evans & Cogswell, Charleston, South Carolina, Russell, D,P,, D,M, Neal, J, Wright, R,L, Jolley, B,S, Baldwin, G,N, Ervin and N,A, Reichert, 2011, Riparian stabilization with Arundinaria gigantea in Choctaw land, Mississippi, Joint meeting of the Intern, and Amer, Bamboo Society, Lafayette, LA, 13-16 Oct, Schoonover, J,E,, K,W,J, Williard, C, Blattel, and C, Yocum, 2010, The utility of giant cane as a riparian buffer species in southern Illinois agricultural landscapes, Agroforest Systems 80:97-107, Scott, J,A, 1986, The Butterflies of North America, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, Silberhorn, G, 1996, Cane Arundinaria gigantea (Walt,) Muhl, Technical Report No, 96-7, Wetlands Program, School of Marine Science, Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary, Gloucester Point, Virginia, Speck, F,G, 1920, Decorative art and basketry of the Cherokee, Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 2(2):53-86, _____, 1941, A list of plant curatives obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana, Primitive Man 14:49-75, Stewart, M,A, 2007, From king cane to king cotton: razing cane in the Old South, Environmental History 12:59-79, Sturtevant, W,C, 1955, The Mikasuki Seminole: medical beliefs and practices, Ph,D, Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, Swanton, J,R, 1931, Source material for the social and ceremonial life of the Choctaw Indians, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 103, _____, 1942, Source material on the history and ethnology of the Caddo Indians, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 132, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D,C, _____, 1946, The Indians of the Southeastern United States, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 137, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D,C, Taylor, J,E, 2006, Arundinaria gigantea, In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online], U,S, Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer), Available: http://www,fs,fed,us/database/feis/, Thomas, B,G,, E,P, Wiggers, and R,L, Clawson, 1996, Habitat selection and breeding status of Swainson’s warblers in Southern Missouri, The Journal of Wildlife Management 60(3):611-616, Wells, B,W, and L,A, Whitford, 1976, History of streamhead swamp forests, pocosins, and savannahs in the southeast, J, Elisha Mitchell Sci, Soc, 92:148-150, Prepared By: M, Kat Anderson and T, Oakes, USDA NRCS National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC, Citation Anderson, M,K, and T, Oakes, 2011, Plant Guide for Giant Cane Arundinaria gigantea, USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401,

Fact Sheet

Alternate Names

cane, switchcane

Uses

Giant cane provides high-quality forage for cattle, horses, hogs, and sheep. It is valued for summer grazing in northern part of range and for winter grazing in states along the gulf coast. Stems of this grass are also used for fishing poles, pipe stems, baskets, and mats.

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status and wetland indicator values.

Description

Giant cane is a native, warm-season, robust, rhizomatous perennial grass. The height is between 4 and 20 feet. The leaf blade is 5 to 12 inches long, at least 1/2 inch wide, and tapers to a sharp point. Generally, it has groups of 3 to 5 blades at end of small branches and a short petiole between the blade and sheath. The leaf sheath is rounded and overlapping. The ligule is a row of short hair. The stem is hollow, woody. The seedhead is an open panicle with 8 to 12 spikelets per seedhead. Distribution: For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site.

Management

Overgrazing and uncontrolled burning easily kills this grass. For maximum production, no more than 50 percent of current year's growth by weight should be grazed off at any season. Controlled burning should be done under ideal humidity, soil moisture, and wind conditions no more than every 3 to 4 years. Deferred grazing for at least 90 days during summer every 2 to 3 years improves plant vigor. Overgrazed stands require complete protection from grazing and fire during the growing season to allow plants to regain vigor.

Establishment

Giant cane produces green leaves and stems all year, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Giant Cane., It grows vigorously from rhizomes and from auxiliary buds at basal nodes, It also grows in small colonies, thickets, and large canebrakes as well as makes vigorous growth under a dense stand of trees, It is adapted to moist soils along riverbanks and in bottomlands and similar sites, It does best on soils of high fertility, Cultivars, Improved and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Please contact your local NRCS Field Office,

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Moisture Use | Medium |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | Medium |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | Low |

| Cold Stratification Required | No |

| Drought Tolerance | Medium |

| Fertility Requirement | Medium |

| Fire Tolerance | High |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 180 |

| Hedge Tolerance | High |

| pH, Maximum | 6.9 |

| pH, Minimum | 5.0 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Maxim | 7200 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Minim | 3700 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 100 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 24 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 18 |

| Salinity Tolerance | Low |

| Shade Tolerance | Intolerant |

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | -23 |

Morphology/Physiology

| After Harvest Regrowth Rate | Rapid |

|---|---|

| Shape and Orientation | Erect |

| Toxicity | None |

| Active Growth Period | Spring |

| Bloat | None |

| C:N Ratio | High |

| Coppice Potential | No |

| Fall Conspicuous | Yes |

| Fire Resistant | No |

| Flower Conspicuous | No |

| Foliage Color | Dark Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Dense |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Dense |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | No |

| Resprout Ability | No |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Lifespan | Long |

| Leaf Retention | No |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Height, Mature (feet) | 25.0 |

| Growth Rate | Rapid |

| Growth Form | Rhizomatous |

| Foliage Texture | Medium |

Reproduction

| Vegetative Spread Rate | Rapid |

|---|---|

| Small Grain | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | Yes |

| Seed Spread Rate | None |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | No |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Cuttings | Yes |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

| Propagated by Container | Yes |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | No |

| Commercial Availability | Routinely Available |

| Propagated by Seed | No |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | No |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | No |

| Protein Potential | Low |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | No |

| Palatable Graze Animal | Medium |

| Palatable Browse Animal | Medium |

| Nursery Stock Product | Yes |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | No |

| Fodder Product | Yes |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | No |