Coastal Panicgrass

Scientific Name: Panicum amarum Elliott var. amarulum (Hitchc. & Chase) P.G. Palmer

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | PAAMA2 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Graminoid |

| Native Locations | PAAMA2 |

Plant Guide

Description

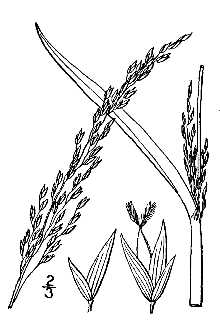

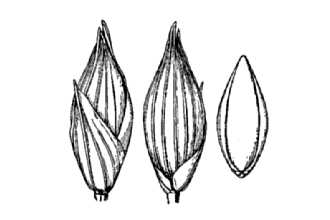

General: Coastal panicgrass is a native, warm-season, clump forming, rhizomatous, perennial grass that grows 3-7 feet tall (Fernald, 1950; Surrency and Owsley, 2006). Its blueish green leaves grow from 8-20 inches long and up to 0.5 inches wide (Tiner, 2009; USDA-NRCS, 2012). Robust stems with a diameter of up to 0.5 inches form a hard, knotty base (Gleason and Conquist, 1963; USDA-NRCS, 2012). Narrow, densely flowered panicles up to 2 feet long form from July to August (Hough, 1983; Tiner, 2009). Flowers produce bright orange anthers. Elliptically shaped gray to tan seed 0.06-0.09 inches long and 0.04-0.05 inches wide (Palmer, 1975) is produced October through November (Hough, 1983; Lorenze et al., 1991; Tiner, 2009). Coastal panicgrass is often mistaken for bitter panicgrass (Panicum amarum Elliott var. amarum), a closely related species. Coastal panicgrass tends to have a more erect, bunch forming habit while bitter panicgrass tends to be more prostrate. Panicle width and flower density have also been used to distinguish the two varieties. Bitter panicgrass has narrower and more sparsely flowered panicles compared to the wider and heavily flowered panicles of coastal panicgrass. These characteristics are at least somewhat impacted by ecological conditions with differences becoming more pronounced at the northern end of the species range and less distinct at the southern end of the range (Palmer, 1975). Distribution: Coastal panicgrass commonly occurs on the dunes of sandy coastal beaches from the Northeast United States to Mexico. The widely accepted native range is along the east coast from New Jersey to as far south as the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico (Lonard and Judd, 2011). Coastal panicgrass is rare in Rhode Island but it is reported to occur as far north as Barnstable County, Massachusetts (Tiner, 2009; USDA-NRCS, 2019). It can be grown in USDA hardiness zones 7a-12b but may winterkill during especially harsh winters at the northern extent of the zone and inland (USDA-NRCS, 2012). For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Coastal panicgrass most frequently grows in tufts in the coastal dune environment from the leeward side of the primary dune in the pioneer zone to the scrub zone in association with American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata), saltmeadow cordgrass (Spartina patens), seaoats (Uniola paniculata), seacoast marsh elder (Iva imbricata), devil’s-tongue (Opuntia humifusa), amberique-bean (Strophostyles helvola), southeastern wildrye (Elymus glabriflorus), partridge pea Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Guide Coastal panicgrass (Panicum amarum Elliott var. amarulum). Photo by Scott Snell, USDA-NRCS, Plant Materials Program. (Chamaecrista fasciculata), Adam’s needle (Yucca filamentosa), hairawn muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris), shore little bluestem (Schizachyrium littorale), common evening primrose (Oenothera biennis), Carolina rose (Rosa carolina), gulf croton (Croton punctatus), seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), largeleaf pennywort (Hydrocotyle bonariensis), yaupon (Illex vomitoria), wax myrtle (Morella cerifera), northern bayberry (Morella pensylvanica), eastern baccharis (Baccharis halimifolia), winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), peppervine (Nekemias arborea), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia), devilwood (Osmanthus americanus), beach plum (Prunus maritima), eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), and live oak (Quercus virginiana) (Graetz, 1973; Slattery et al., 2003; Wootton et al., 2016). Coastal panicgrass also occurs along the borders of intertidal marshes and has been reported to colonize disturbed sandy sites (Anderson and Alexander, 1985; Hill, 1986).

Adaptation

Coastal panicgrass is extremely drought resistant and salt spray tolerant making it well adapted to its indigenous habitat on the coastal dunes (Graetz, 1973; Lorenze et al,, 1991), It is a barrier plant in the dune pioneer zone, protecting more salt susceptible species beyond the primary dune, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Coastal Panicgrass., In a study examining the salinity tolerance of American beachgrass, saltmeadow cordgrass, seaoats, and coastal panicgrass seedlings, Seneca (1972) found coastal panicgrass to be the second most salt tolerant of the four species tested based on growth response, Miller (2013) also found coastal panicgrass can withstand occasional saltwater treatments, Coastal panicgrass is most adapted to the well-drained, sandy soils of the Atlantic Coastal Plains but will tolerate poorly drained soils (Lorenze et al,, 1991; USDA-NRCS, 2006 a), It can withstand a soil pH range of 4,5-7,5 (Salon and Miller, 2012), It is intolerant of shade and does not do well as an understory plant (Lorenze et al,, 1991),

Uses

Conservation Practices: Coastal panicgrass has an upright growth habit, is resistant to lodging, is easily established, long-lived, and manageable. These characteristics make it an ideal candidate in Hedgerow (422), Vegetative Barrier (601), and Herbaceous Wind Barrier (603) plantings (USDA-NRCS, 2012). Belt (2015) reported coastal panicgrass as a top performer in a trial evaluating the ability of 40 species to reduce or limit the spread of dust, odor, and ammonia emitted by poultry farm exhaust fans. Additionally, coastal panicgrass has proven applications for the NRCS Critical Area (342) standard for dune stabilization plantings, mined land reclamation sites, and dredged material revegetation (Knight et al., 1980; USDA-NRCS, 2012). It is one of the few dune stabilization species to be successfully established by direct seeding (Wootton et al., 2016). Coastal panicgrass may also be used to stabilize other Critical Area sites e.g. gravel pits, dikes, and road banks (USDA-NRCS, 2006 a). Coastal panicgrass could also be applied to long term management plans using the NRCS Herbaceous Weed Treatment (315) standard. Planting coastal panicgrass in coastal dune environments is recommended as a means of discouraging the recolonization of the invasive Asiatic sand sedge (Carex kobomugi) following successful treatment control measures (TLC, 2017). Wildlife: Coastal panicgrass provides food and shelter for a variety of species including songbirds, waterfowl, and small mammals (Slattery et al., 2003). The calorie dense seed provides doves and quail with a concentrated energy source in the late fall/early winter when other food sources may be scarce (Surrency and Owsley, 2006). In a study of grassland bird habitat frequented for breeding purposes by the regionally rare grasshopper sparrow, Rudnicky et al. (1997) reported coastal panicgrass as a dominant species at one of the sites tested. Pernell and Soots (1975) reported a highly successful herring gull colony with nests next to bunches of coastal panicgrass. In an additional study of the nesting habits of sea birds, McNair and Gore (2000) reported coastal panicgrass as the dominant vegetation on a Florida island for two breeding seasons. Coastal panicgrass habitat is the preferred habitat of eight subspecies of beach mice: Alabama beach mouse, Perdido Key beach mouse, Santa Rosa beach mouse, Choctawatchee beach mouse, St. Andrew beach mouse, Anastasia Island beach mouse, Southeastern beach mouse, and pallid beach mouse. With the exception of the Santa Rosa beach mouse, all have been listed as threatened or endangered by either the United States Fish and Wildlife Service or the Florida Fish and

Wildlife

Conservation Commission (Bird et al., 2002). The beach mouse subspecies (the pallid beach mouse has been declared extinct) depend on coastal panicgrass for shelter and its seed as a constituent of their diet (Dziergowski, 2009; Lonard and Judd, 2011). Forage: Coastal panicgrass is readily grazed by cattle and provides a sufficient level (140 g kg-1) of crude protein to support beef production (Mehaffey et al., 2005). In a study examining the performance of tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus) bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), yellow bluestem (Bothriochloa ischemum), and coastal panicgrass pasture systems, the coastal panicgrass pasture system produced the greatest steer gains during the warm-season grass growth period (Burns et al., 2012). However, Burns et al. (2012) reported that coastal panicgrass pastures could not support the same level of steer stocking as tall fescue/bermudagrass pasture systems without signs of severe stand weakening following a second year of grazing. The researchers concluded that coastal panicgrass pastures could be advantageous for grazing if incorporated into a rotational stocking system. Ornamental/landscaping: The blueish green leaves and bright, vibrant orange anthers of coastal panicgrass make it a desirable plant for ornamental and landscaping purposes (Craig, 1976). This is especially true for landowners in coastal communities whose properties are adjacent to or within the vicinity of the dune environment. Many traditional ornamental plants cannot tolerate the salt spray and/or the native sandy soils of the barrier islands and littoral areas where most coastal communities occur. Biofuel Production: In studies examining the biofuel potential of warm season grasses, coastal panicgrass has displayed greater biomass production than some big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), eastern gamagrass (Tripsacum dactyloides), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans) varieties (Viands, et al., 2010). The average annual yield of ‘Atlantic’ coastal panicgrass was slightly over 6 dry tons/acre after 4 years of data collection (USDA-NRCS, 2012). Coastal panicgrass’ tolerance for saline conditions may make it the ideal choice as a biofuel crop on marginal agricultural land that has been impacted by saltwater inundation (Miller, 2016).

Ethnobotany

Various species of panicgrass were used for medicinal purposes by Native Americans. The Seminole Tribe used panicgrass medicinally as an antirheumatic (external), cough medicine, pulmonary aid, and throat aid (Hutton, 2010). The Natchez and Creek Tribes used panicgrass to treat malaria fevers (Hutton, 2010). The Miccosukee Tribe used panicgrass as a treatment for ‘gopher-tortoise sickness’ (Lamphere, 2006). The Cherokee Tribe padded their moccasins with stems from panicgrass (Lamphere, 2006).

Status

Threatened or Endangered: Coastal panicgrass is listed as endangered in Pennsylvania, threatened in Connecticut, and as a species of special concern in Rhode Island (USDA-NRCS, 2019). Coastal panicgrass is ranked as “S3” in New Jersey meaning “Not yet imperiled in state but may soon be if current trends continue” (Snyder, 2016). Wetland Indicator: FAC for Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain region; FACU for all other regions in which it occurs (USACE, 2018). Weedy or Invasive: Coastal panicgrass is listed as introduced in Massachusetts (CZM, 2019). This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not properly managed. Please consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding its status and use. Please consult the PLANTS Web site (http://plants.usda.gov/) and your state’s Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Planting Guidelines

Although establishment in the coastal dune environment via vegetative plugs is the recommended method, establishment via direct seeding is possible under appropriate conditions (Lorenze et al., 1991). Soil moisture is critical with best results achieved in moist sand (Darovec et al., 1975; Slattery et al., 2003). Direct seeding into saline environments is also a feasible option. Coastal panicgrass seed will germinate at salinity levels almost equal to the levels that seedlings can tolerate (Seneca, 1972). Plant seed 1-3 inches deep; shallower for finer textured soils with higher silt content and deeper for coarse textured soils. Mulching the seeding area will improve establishment results (Craig, 1991; USDA-NRCS, 2012). In replicated seeding Flowering spikelet of coastal panicgrass displaying orange anthers and purple stigmas. Photo by Scott Snell, USDA-NRCS, Plant Materials Program.

Management

For wildlife habitat applications, mowing is a treatment option to control undesired vegetation. Coastal panicgrass withstands mowing well. Rudnicky et al. (1997) reported it to be a dominant species following mowing treatments of grassland bird habitat. Prescribed burning suppresses weeds, controls the spread of unwanted perennial species, and kills some weed seeds (USDA/EPA, n.d.). In addition to weed control, controlled burning assists in nutrient recycling and stimulates seed production (USDA-NRCS, 2006 a). Selective herbicide applications are a reliable means of weed control (USDA/EPA, n.d.). Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA-NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Fertilizer recommendations for coastal panicgrass are inconsistent. Top or side dressed single application and split applications (June and August) of 10-10-10 fertilizer applied at rates ranging from 400-600 lb/acre annually have been recommended for both seed production fields and coastal dune plantings (USDA-NRCS, 2007; USDA-NRCS, 2006 a). More recent fertilization recommendations for the coastal dune environment address water quality concerns due to excess nutrients from overfertilization. In response, lower fertilization rates (20-30 lb/acre nitrogen) and alternative nutrient sources (slow release fertilizers and organic options) are recommended for coastal dune sites (Wootton et al., 2016). In all cases, base fertilizer applications on soil test results of the planting site. Contact your local agricultural extension for soil test analysis and fertilizer application recommendations prior to implementing a fertilization plan.

Pests and Potential Problems

In the Mid-Atlantic coastal dune environment, coastal panicgrass has been reported to be negatively impacted by plant parasitic nematodes. Seliskar and Huettel (1993) reported a correlation between the presence of plant parasitic nematodes and reduction of plant health. Coastal panicgrass did not show any signs of plant stress the initial year that nematodes were found, but signs of stress were reported in following years. Coastal panicgrass is a reported host of multiple fungal rust species (Farr and Rossman, 2019).

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

Coastal panicgrass is listed as introduced in Massachusetts (CZM, 2019; Lonard and Judd, 2011). Coastal panicgrass seed can remain viable for up to 5 years in its natural habitat without any specialized storage (USDA-NRCS, 2012). Although initial seed dispersal is limited to no more than 20 feet, consumption by wildlife and floatation on moving waters are two possible means by which seed could become distributed greater distances to non-native habitats (Lonard and Judd, 2011; USDA-NRCS, 2012). Coastal panicgrass rhizomes are a viable means of regeneration in favorable conditions and may spread 3 feet in a single growing season (USDA-NRCS, 2012). Coastal panicgrass has been reported to invade the frontal dune system but will not become well established due to the inevitable burial of the shifting sands (Palmer, 1975). Coastal panicgrass has not been reported to cause any allelopathic effects (USDA-NRCS, 2012).

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Coastal panicgrass is propagated vegetatively or by seed (USDA-NRCS, 2006 a). Seed production fields reach maturity and become productive in two growing seasons. Up to 300 lb/acre of cleaned seed is produced by properly managed seed production fields (USDA-NRCS, 2012). Seed production is stimulated by annual prescribed burns in late winter or early spring (USDA-NRCS, 2006 a). Coastal panicgrass seed ranges from 325,000-350,000 seeds/lb (Dickerson et al., 1997; USDA-NRCS, 2012). Laboratory viability tests of seed produced at the New Jersey Plant Materials Center from 2001 to 2020 ranged from 70 to 94 percent with an average rate of 84 percent. Coastal panicgrass maintains excellent longevity under ideal storage conditions. Seed stored in a seed cooler (4°C and 40 percent relative humidity) at the New Jersey Plant Materials Center maintained 75 percent or greater viability rates after 9 years of storage with germination rates increasing after storage in some instances. Harvest seed with hand tools (hand sickles) or on a greater scale with mechanical agricultural equipment. Seed has been successfully harvested at the New Jersey Plant Materials Center using a plot harvester with a standard grain head. Harvester settings depend on a multitude of variables (equipment, environmental conditions, management methods, etc.), but the following ranges have proven satisfactory: cylinder spacing of 0.26-0.28 inch, cylinder speed of 1000 rpm, and a low air flow setting. Seed is typically harvested in early October in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. Seed cleaning methods depend upon the harvest method. If harvested with hand tools, thresh seed before attempting to separate the chafe from the seed. Thresh seed with mechanized seed cleaning equipment or use a manual rubbing board. Small harvest amounts can be mechanically threshed using a slightly modified kitchen blender (Scianna, 2004). Air and screen seed cleaning equipment readily separates chafe from seed using 0.31-0.14 inch round holes for the top screen and 1/22 inch round holes for the bottom screen. Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) These plant materials are readily available from commercial sources. ‘Atlantic’ coastal panicgrass is a cultivar developed and released in 1981 by the Cape May, NJ Plant Materials Center, USDA-NRCS. The source material for Atlantic was collected from Back Bay Wildlife Refuge, Princess Anne County, Virginia. It was selected for seedling vigor, uniform characteristics, and rust resistance (USDA-NRCS, 2006 b). It is recommended for critical area, forage, hedge row, salt affected sites, and wildlife applications (USDA-NRCS, 2012)

Literature Cited

Anderson, L.C. and L.L. Alexander. 1985. The vegetation of Dog Island, Florida. Florida Scientist 48(4): 232-251. Belt, S.V. 2015. Plants tolerant of poultry farm emissions in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. Maryland Plant Materials Final Report. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Norman A. Berg National Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, MD. Bird, B.L., L.C. Branch, and M.E. Hostetler. 2002. Beach mice, WEC 165. University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Extension, Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Department, Gainesville, FL. Burns, J.C., D.S. Fisher, and K.R. Pond. 2012. Steer performance and pasture productivity of a tall fescue-bermudagrass system compared with yellow bluestem and coastal panicgrass. Prof. Anim. Sci. 28: 272-283. CZM (Coastal Zone Management). 2019. Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts – grasses and Perennials [Online]. Available at https://www.mass.gov/info-details/coastal-landscaping-in-massachusetts-grasses-and-perennials#coastal-panic-grass- (accessed 17 December 2019). Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM), Storm Smart Coasts Program, Boston, MA. Craig, R.M. 1976. Grasses for coastal dune areas. Proc. FL State Hort. Soc. 89: 353-355. Craig, R.M. 1991. Plants for coastal dunes of the Gulf and South Atlantic Coasts and Puerto Rico. Agriculture Information Bulletin 460. USDA-Soil Conservation Service, Gainesville, FL. Darovec, J.E. et al. 1975. Techniques for coastal restoration and fishery enhancement in Florida. Florida Department of Natural Resources, Marine Research Laboratory, St. Petersburg, FL. Dickerson, J. et al. 1997. Vegetating with native grasses in Northeastern North America. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Syracuse, NY and Ducks Unlimited, Memphis, TN. Duncan, W.H. and M.B. Duncan. 1987. The Smithsonian guide to seaside plants of the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. Dziergowski, A. 2009. Species Account for Anastasia Island beach mouse (Peromyscus polionotus phasma) and Southeastern beach mouse (Peromyscus polionotus niveiventris). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Jacksonville, FL. Farr, D.F. and A.Y. Rossman. 2019. Fungal Databases, U.S. National Fungus Collections [Online]. Available at https://nt.ars- grin.gov/fungaldatabases/ (accessed 18 Dec. 2019). USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Washington D.C. Fernald, M.L. 1950. Gray’s manual of botany. American Book Company, New York. Gleason, H.A. and A. Cronquist. 1963. Manual of vascular plants of Northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York. Graetz, K.E. 1973. Seacoast plants of the Carolina for conservation and beautification. Sea Grant Publication, Chapel Hill, NC. Hill, S.R. 1986. An annotated checklist of the vascular flora of Assateague Island (Maryland and Virginia). Castanea, 51, 265–305. Hough, M.Y. 1983. New Jersey wild plants. Harmony Press, Harmony, NJ. Hutton, K. 2010. A comparative study of the plants used for medicinal purposes by the Creek and Seminoles Tribes. Graduate Theses and Dissertations, University of South Florida. Knight, D.B., P.L. Knutson, and E.J. Pullen. 1980. An annotated bibliography of seagrasses with emphasis on planting and propagation techniques. Miscellaneous report No. 80-7. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Coastal Engineering Research Center, Fort Belvoir, VA. Lamphere, J. 2006. Plant Guide for bitter panicum (Panicum amarum Ell.). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Golden Meadows Plant Materials Center, Galliano, LA. Lonard, R.I. and F.W. Judd. 2011. The biological flora of coastal dunes and wetlands: Panicum amarum S. Elliott and Panicum amarum S. Elliott var. amarulum (A.S. Hitchcock and M.A. Chase) P. Palmer. J. Coast. Res. 27(2): 233-242. Lorenze, D.G., W.C. Sharp, and J.D. Ruffner. 1991. Conservation plants for the Northeast. USDA-Soil Conservation Service. McNair, D.B. and J.A. Gore. 2000. Recent breeding of Caspian terns in Northwest Florida. Florida Field Naturalist 28(1): 30- 32. Mehaffey, M.H., D.S. Fisher, and J.C. Burns. 2005. Photosynthesis and nutritive value in leaves of three warm-season grasses before and after defoliation. Agron. J. 97: 755-759. Miller, C.M. 2013. Workshop: Living Shorelines for Coastal Erosion Protection in a Changing World, Hauppauge, NY. 15 May 2013. New York Sea Grant, NY. Miller, C.M. 2016. Adaptive Strategies to Alleviate the Impacts of Sea Level Rise. Mid-Atlantic Crop Management School, Ocean City, MD. 17 November 2016. [Online]. Available at https://youtu.be/ieB0DQkWlko (accessed 16 December 2019). Palmer, P.G. 1975. A biosystematic study of the Panicum amarum-P. Amarulum complex (Gramineae). Brittonia 27(2): 142-150. Pernell, J.F. and R.F. Soots. 1975. Herring and great black-backed gulls nesting in North Carolina. The Auk 92(1): 154-157. Rudnicky, J.L., W.A. Patterson III, and R.P. Cook. 1997. Experimental use of prescribed fire for managing grassland bird habitat at Floyd Bennet Field, Brooklyn, New York in Grasslands of Northeastern North America: Ecology and conservation of native and agricultural landscapes. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, MA. Salon, P.R. and C.F. Miller. 2012. A guide to conservation plantings on critical areas for the Northeast. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Big Flats Plant Materials Center, Corning, NY. Scianna, J.D. 2004. Blending dry seeds clean. Native Plants 5(1): 44-55. Seliskar, D.M. and R.N. Huettel. 1993. Nematode involvement in the dieout of Ammophila breviligulata (Poaceae) on the Mid-Atlantic coastal dunes of the United States. J. Coastal Research 9(1): 97-103. Seneca, E.D. 1972. Seedling response to salinity in four dune grasses from the outer banks of North Carolina. Ecology 53(3): 465-471. Slattery, B.E., K. Reshetiloff, and S.M. Zwicker. 2003. Native plants for wildlife habitat and conservation landscaping: Chesapeake Bay Watershed. U.S. Department of Interior, Fish & Wildlife Service. Snyder, D.B. 2016. List of Endangered Plant Species and Plant Species of Concern [Online]. Available at https://www.nj.gov/dep/parksandforests/natural/heritage/njplantlist.pdf (accessed 25 November 2019). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Parks and Forestry, Trenton, NJ. Surrency, D. and C.M. Owsley. 2006. Plant Materials for Wildlife. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Jimmy Carter Plant Materials Center. Americus, GA. Tiner, R.W. 2009. Field guide to tidal wetland plants of the Northeastern United States and neighboring Canada. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA. TLC (Technical Learning College). 2017. Invasive Plants Identification and Control, Professional Development Continuing Education Course [Online]. Available at https://www.abctlc.com/downloads/courses/InvasivePlants.pdf (accessed 19 December 2019). Chino Valley, AZ. US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). 2018. National Wetland Plant List v3.3 – Species Detail Tool. [Online]. Available at https://www.branford-ct.gov/sites/default/files/field/files-docs/using_native_grasses_for_ecological_restoration.pdf (accessed 18 Dec. 2019). USDOD-Army Corps of Engineers. Washington, DC. USDA/EPA. n.d. Using Native Grasses for Ecological Restoration [Online]. Available at https://www.mass.gov/info-details/coastal-landscaping-in-massachusetts-grasses-and-perennials#coastal-panic-grass- (accessed 17 December 2019). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center. Cape May, NJ. USDA-NRCS. 2006. Plant fact sheet for Panicum amarum Ell. Var. amarulum (A.S. Hitchc. & Chase) P.G. Palmer, Coastal panicgrass. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Somerset, Plant Materials Program. USDA-NRCS. 2006. Release brochure for coastal panicgrass ‘Atlantic’ (Panicum amarum Ell. Var. amarulum). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center. Cape May, NJ. USDA-NRCS. 2007. Planting guide for establishing coastal vegetation on the Mississippi Gulf coast. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Jamie L. Whitten Plant Materials Center, Coffeeville, MS. USDA-NRCS. 2012. Release brochure for coastal panicgrass ‘Atlantic’ (Panicum amarum Ell. Var. amarulum). USDA- Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center. Cape May, NJ. USDA-NRCS. 2019. Plants Database – Panicum amarum Elliott var. amarulum (Hitchc. & Chase) P.G. Palmer, coastal panicgrass [Online]. Available at https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=PAAMA2 (accessed 25 November 2019). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service. Viands, D.R., H. Hansen, and H. Mayton. 2010. Production/Evaluation of Grasses for Energy Conversion in NNY in Northern New York Agricultural Development Program. Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station, Ithaca, NY. Wootton, L., J. Miller, C. Miller, M. Piik, A. Williams, and P. Rowe. 2016. Dune Manual. New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium, Highlands, NJ. Citation Snell, S.C. 2020. Plant Guide for coastal panicgrass (Panicum amarum Elliott var. amarulum). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May, NJ. Published: September 2020 Edited: 20Aug2020 hld For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or Conservation District at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/ and visit the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov/ or the Plant Materials Program web site: http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov. PLANTS is not responsible for the content or availability of other Web sites. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at How to File a Program Discrimination Complaint and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410; (2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or (3) email: program.intake@usda.gov. USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.