Taeniatherum asperum auct. non (Simonkai) Nevski

Scientific Name: Taeniatherum asperum auct. non (Simonkai) Nevski

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | TAAS2 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Annual |

| Growth Habits | Graminoid |

| Native Locations | TAAS2 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Medusahead wildrye, medusahead rye, rough medusahead.

Uses

Erosion Control: Medusahead is a winter annual grass with a shallow root system. It is a very poor erosion control plant. Livestock: Medusahead has minimal value for livestock grazing (Sharp and Teasdale 1952, Turner 1965, Davies and Johnson 2008). Hironaka (1961) reported that grazing capacities were reduced as much as 80 percent when medusahead was present. Despite these facts, livestock will graze medusahead when it is in a vegetative stage (Lusk et al. 1961, Horton 1991). The nutritive value of medusahead foliage is comparable to cheatgrass except medusahead has a high level of silica and the season of use is much shorter. Horton (1991) proposed that the high silica level deterred grazing. Grazing values diminish rapidly as the plants mature (Furbush 1953), and is due in part to the awned seeds. The awned seeds can cause injury to eyes, nose, and mouths of grazers (Rice 2005). Wildlife: Well-established medusahead communities have low plant species diversity and have low value for wildlife habitat (Miller et al. 1999). Rabbits will graze medusahead (Sharp et al. 1957). Bodurtha et al. (1989) reported that mule deer will frequent medusahead mixed communities but they will not eat medusahead. Savage et al. (1969) reported that chucker partridge consumed medusahead seeds in a controlled feeding study but further reported that the birds lost weight.

Status

Consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Weediness

Medusahead originates from Eurasia and was first reported in North America in the 1880s (Furbush 1953). By 2003, it occupied approximately 2.3 million acres in 17 western states (Rice, 2005). Pellant and Hall (1994) suggest that 76 million acres of public land is susceptible to invasion by winter annuals including cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum ) and medusahead. Medusahead’s success is largely a result of it being native to a Eurasian region with similar temperature-moisture patterns as found in the Intermountain West and inland valleys of California. Summers are warm and dry; fall, winter, and spring seasons are cool to cold and moist. Diverse native plant communities inhibit colonization of weedy species because these communities more fully exploit soil and moisture resources. Medusahead typically colonizes sites where the existing perennial vegetation has been destroyed or weakened (Miller et al. 1999). However, they also reported that medusahead will colonize native communities but not overrun them until a disturbance frees up resources. Grazing practices can be tied to the success of medusahead. However, eliminating grazing will not eradicate medusahead if it is already present (Wagner et al. 2001). Sheley and Svejcar (2009) reported that even moderate defoliation of bluebunch wheatgrass resulted in increased medusahead density. They suggested that disturbances, such as plant defoliation, limit soil resource capture, which creates an opportunity for exploitation by medusahead. Avoidance of medusahead by grazing animals allows medusahead populations to expand. This creates seed reserves that can infest adjoining areas and cause changes to the fire regime. Transition from a perennial rangeland community to a cheatgrass dominated community has greatly contributed to the success of medusahead. Young et al. (1999) reported that medusahead matures 2-4 weeks later than cheatgrass, and medusahead will replace cheatgrass on soils that have available moisture after the cheatgrass has matured. Medusahead, like cheatgrass, is a fire-adapted species (Davies and Johnson 2008). Both species being winter annuals complete their lifecycle prior to the normal wildfire season. Medusahead biomass is high in silica, degrades slowly, and is highly flammable (McKell et al 1962). Fast burning fires may not generate enough heat to kill seeds lying under the soil surface. Elimination of the shrub component and surface litter by fire exposes bare soil, which is less hospitable to native plant seedlings (Young et al. 1999). Medusahead is a very effective colonizer of fire-denuded soil. Activities such as road building expose bare soil and heavy subsoil. Failure to revegetate exposed soils leaves them prone to medusahead colonization and serves as seed source for adjacent areas. Medusahead alters the nutrient cycling processes from a “conservative” cycle to a “leaky” cycle (Norton et al. 2007). Conservative nutrient cycles allow for rapid recovery of nutrients by diverse plant communities. Leaky nutrient cycles occur when there is a large pulse of nutrients released into the soil and not captured by the plants. Leaky nutrient cycling favors medusahead and greatly impedes establishment of perennial plant communities (Norton et al. 2007).

Description

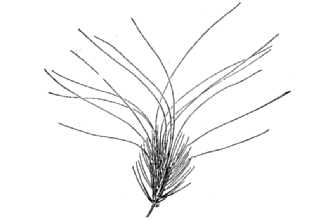

General: Grass family (Poaceae). Medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae ) is a winter annual grass. It is typically 0.15-0.5m (6-20 in) tall and has distinct bristly seed heads. Medusahead germinates in the fall, overwinters as a seedling, and commences growth in the spring. The leaves of seedlings are bright green, upright, and delicate looking (Miller et al. 1999). One or more stems arise from the base of the plant and can be as long as 0.6m but are more commonly 0.2-0.33m in length. Each stem produces a single, short (15-50mm long), bristly, spike-type seed head. The seed heads are similar in appearance to foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum ) and bottlebrush squirreltail (Elymus elymoides), but medusahead seed heads do not disarticulate. The seed heads have 2 sets of bristles; the shorter bristles (20-40mm) protrude at a wide angle to the spike; and longer bristles (40-80mm) are more upright. Each seed head is a spike inflorescence, each node will produce 2-3 spikelets, and each spikelet will contain one viable seed. Twenty or more seeds are produced per seed head (Clausnitzer 1996). Medusahead seed heads and leaf litter degrade slowly and commonly accumulate on the ground and make it easy to identify infestations. Distribution: Medusahead is distributed from Washington to Montana and south to California. It also occurs in Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut. Medusahead is very prominent in the inland valleys of California, Intermountain West including the Great Basin, and is becoming prominent in the Columbia Basin. For current distribution, consult the Plant profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site.

Adaptation

Medusahead is mostly found in degraded ecological sites that have relatively high water holding capacity and/or a high water table. It frequently replaces cheatgrass on heavier clayey soils. It is not common in hot desert environments, high mountains where the snowpack lasts well into the growing season and areas that receive ample summer moisture. Medusahead’s lower moisture limit is 10-inches MAP, but it is most common in the 12-20-inch MAP areas.

Establishment

It is not recommended for seeding due to its very invasive traits, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Taeniatherum asperum auct. non (Simonkai) Nevski.,

Control

Prevention & Containment: Medusahead is slow to invade late seral (good or better condition) rangeland that has a low disturbance regime (Miller et al. 1999, Davies and Svejcar 2008). It commonly follows cheatgrass and replaces cheatgrass on heavy soils (Young et al. 1999). Maintaining a plant community that exploits resources will impede medusahead invasion. For example, established pastures must be seeded to species that compete well with medusahead for available resources and be properly managed. Rangeland communities must be managed for high species diversity and be given ample time for recovery between grazing periods. Medusahead seeds drop within 2m of the plant, which affords an opportunity to use vegetative buffers to contain medusahead (Davies 2008). Tall grasses and shrubs are excellent barriers and could greatly reduce movement from roadside environments to adjoining land. Bio-control: There currently are no biological control agents developed for this species. Two smut diseases and a crown rot have been investigated but do not appear to be viable tools (Miller et al 1999, Coombs et al. 2005) Chemical: Several herbicides provide excellent control of medusahead. Herbicides differ in selectivity, persistence in the environment, grazing restrictions, and many other parameters. Always read the label before applying any herbicide. Foliar active compounds such as glyphosate (trade name: Roundup ™ herbicide, etc.) can be very effective if good coverage is obtained. Applications of foliar active herbicides will be less effective if a heavy thatch intercepts the spray. Soil active compounds such as atrazine (trade name: AAtrex™, etc.) and metribuzin (trade name: Sencor™, etc.) can also be very effective. Aminopyralid (trade name: MilestoneMedushead™) and imazapic (trade name: Plateautm™) are two relatively new compounds on the market that provide foliar control and several months of soil activity. Mechanical: Medusahead is susceptible to tillage. Effective tillage must sever the roots before the plants flower thus preventing seed production. Medusahead can have multiple flushes. Consequently, multiple tillage operations and/or tillage plus other control techniques need to be employed for effective control. Range scalping and chiseling do not provide adequate undercutting of the roots. Desirable range species stimulated by these practices are too slow growing to out-compete medusahead. Mowing must be low enough to remove the seed heads. Burning: Mature medusahead is very flammable. Fire can remove the thatch layer, consume standing vegetation, and even reduce seed levels. Furbush (1953) reported that timing a burn while the seeds were in the milk stage effectively reduced medusahead the following year. He further reported that adjacent unburned areas became a seed source for reinvasion the following year. Fire by itself is an ineffective control practice. Fire eliminates competing vegetation, accelerates loss of top soil, and frees up nutrients. Fire is an excellent tool in combination with other control practices such as application of herbicides. Revegetation: Revegetation is a risky process. Precipitation events must be timely and sufficient during the revegetation establishment year. Medusahead seeds germinate in the fall while most perennial grasses germinate in the spring. This gives medusahead a clear advantage in the spring. Revegetation species must be able to establish quickly and must be capable of withstanding summer drought. Once fully established, revegetation species must be capable of withstanding fire and defoliation. Few species have consistently demonstrated the ability to establish in medusahead sites. Bluebunch wheatgrass seedlings grow far too slowly (Goebel et al. 1988). Crested wheatgrass performs poorly on clay soils (Young et al. 1999). Bottlebrush squirreltail has exhibited the ability to replace medusahead (Hironaka and Sindelar 1975, Arrendondo et al. 1998). ‘Sherman’ big bluegrass performed well in revegetation trials (Young et al. 1999). They further reported that additional trials were needed to confirm their results. When practical, one year of fallow should be employed to control existing medusahead plants and reduce the soil seed bank. Failure to control medusahead when revegetating will result in failure. Cultural Practices: Vehicles, clothing, camp gear, and pets should be cleaned of adhering seed after driving, camping, and walking in medusahead-infested areas. Livestock should not be moved from infested pastures to fields free of medusahead. Excessive roadside and rangeland disturbance should be avoided.

References

Arrendondo, J.T., T.A. Jones, and D.A. Johnson. 1998. Seedling growth of intermountain perennial and weedy annual grasses. J. Range Manage 51:584-589. Bodurtha, T.S., J.P. Peek, J.L. Lauer. 1989. Mule deer habitat use related to succession in a bunchgrass community. J Wildl Manage 53:314-319. Clausnitzer, D. 1996. Field study of competition between medusahead ( Taeniatherum caput-medusae subsp. asperum [Simk.] Melderis) and squirreltail (Elymus elymoides [Raf.] Swezey). M.S. Thesis, Dept Rangeland Resources, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. Coombs, E. M., J.K. Clark, G.L. Piper. 2004. Medusahead ryegrass. In: Coombs, E. M., J.K. Clark, G.L. Piper (eds.). Biological control of invasive plants in the United States. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR. Davies, K.W. 2008. Medusahead dispersal and establishment in sagebrusk steppe plant communities. Rangeland Ecol Manage 61:110-115. Davies, K.W. and D.D. Johnson. 2008. Managing medusahead in the Intermountain West is at a critical threshold. Rangelands 30:13-15. Furbush, P. 1953. Control of medusahead on California ranges. J Forest 51:118-121. Goebel, C.J., M. Tazl, and G.A. Harris. 1988. Secar bluebunch wheatgrass as a competitor to medusahead. J Range Manage 41:88-89. Hironaka, M. 1961. The relative rate of root development of cheatgrass and medusahead. J Range Manage 14:263-267. Hironaka, M. amd B.W. Sindelar. 1975. Growth characteristics of squirreltail seedlings in competition with medusahead. J Range Manage 28:283-285. Horton, W.H. 1991. Medusahead: importance, distribution, and control. In: James, L.F. J.O. Evans, M.H. Ralphs and R.D. Child (eds.). Noxious range weeds. Westview press. Boulder, CO. Lusk, W.C., M.B. Jones, P.J. Torell, and C.M. McKell. 1961. Medusahead palatability. J Range Manage 14:248-251. McKell, C.M., A.M. Wilson, and B.L. Kay. 1962. Effective burning of rangelands infested with medusahead. Weeds 10:125-131. Miller, H.C., D. Clausnitzer, and M.M Borman. 1999. Medusahead. In: Sheley, R.L. and J.K. Petroff (eds.). Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR. Norton, J.B., T.A. Monaco, and U. Norton. 2007. Mediterranean annual grasses in western North America: kids in a candy store. Plant Soil 298:1-5. Pellant, M. and C. Hall. 1994. Distribution of two exotic grasses in intermountain rangelands: ststus in 1992. In: Monsen, S.B. and S.G. Kitchen (eds.). Proc. Ecology and management of annual rangelands. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech Report INT-GTR- 313. Ogden, UT. Rice, P.M. 2005. Medusahead [Taeniatherum caput- medusae (L.) Nevski]. In: Duncan, C.L. and J.K. Clark (eds.) Invasive plants of range and wildlands and their environmental, economic, and societal impacts. Weed Sci Soc America. Lawrence, KS. Savage, D.E., J.A. Young, and R.A. Evans. 1969. Utilization of medusahead and downy brome caryopses by chukar partridges. J Wildl Manage 33:975-978. Sharp L.A. and E.W. Teasdale. 1952. Medusahead, a problem on some Idaho ranges. Res. Note(3) Forest, Wildlife, and Range Exp. Sta. U. Idaho, Moscow, ID. Sharp, L.A., M. Hironaka, and E.W. Teasdale. 1957. Viability of medusa-head (Elymus caput-medusae L.) seed collected in Idaho. J Range Manage 10:123-126. Sheley, R.L. and T.J. Svejcar. 2009. Reponse of bluebunch wheatgrass and medusahead to defoliation. Rangeland Ecol Manage 62:278-283. Turner, R.B. 1965. Medusahead control and management studies in Oregon. In: Proc. of the cheatgrass symposium, Vale, Oregon. Bureau Land Management, Portland, Oregon. Wagner, J.A., R.E. Delmas, and J.A. Young. 2001. 30 years of medusahead: return to fly blown-flat. Rangelands 23:6-9. Young J.A., C.D. Clements, and G. Nader. 1999. Medusahead and clay: the rarity of perennial seedling establishment. Rangelands 21:19-23 .

Prepared By

Mark Stannard, Manager, USDA, NRCS, Plant Materials Center, Pullman, Washington Daniel G. Ogle, Plant Materials Specialist, USDA, NRCS, Boise, Idaho Loren St. John, Manager, USDA, NRCS, Plant Materials Center, Aberdeen, Idaho Citation M.E. Stannard, D.O. Ogle, and L. St. John. 2010. Plant guide for medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusae Published August, 2010 Edited: 02Mar2010 ms, 09jun2010 dgo, 02Mar2010 lsj, 08Jun201010 mes, 09jun2010 jab, 12Jul2010 ljtg For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or