Sagittaria viscosa C. Mohr

Scientific Name: Sagittaria viscosa C. Mohr

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | SAVI12 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herb |

| Native Locations | SAVI12 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Arrowhead, Indian potato, tule potato, wapato

Uses

Ethnobotanic: Sagittaria is an aquatic plant with tuberous roots that can be eaten like potatoes. Lewis and Clark found it at the mouth of the Willamette and considered it equal to the potato, and valuable for trade. Indian women collected it in shallow water from a canoe, or waded into ponds or marshes in the late summer and loosened the roots with their toes. The roots would rise to the top of the water where they were gathered and tossed into floating baskets. Today, the tubers are harvested with a hoe, pitchfork, or rake. Tubers are baked in fire embers, boiled, or roasted in the ashes. Tubers are skinned and eaten whole or mashed. After roasting, some tubers were dried and stored for winter use. The Chippewa gathered the "Indian potatoes" in the fall, strung them, and hung them overhead in the wigwam to dry. Later they were boiled for use. The tubers of Sagittaria species were eaten by many different indigenous groups in Canada, as well as many groups of Washington and Oregon (Kuhnlein and Turner 1991). The tubers were also widely traded from harvesting centers to neighboring areas. The tubers were also a major item of commerce on the Lower Columbia in Chinook Territory. Katzie families owned large patches of the plant and clearing the patches claimed ownership. Family groups would camp beside their claimed harvesting sites for a month or more. A species of Sagittaria grows in China, and is sold in the markets of China and Japan as food, the corms being full of starch. Sagittaria latifolia is extensively cultivated in the San Francisco Bay area in California to supply the Chinese markets, and the tubers are commonly to be found on sale. The Chinese, on coming to California, used it for food and may have cultivated it somewhat. In so doing, they are believed to have extended its range into the southern part of the state (Mason 1957). Medicinally, the Maidu of California used an infusion of arrowhead roots to clean and treat wounds. The Navajo use these plants for headaches. The Ojibwa and the Chippewa used Sagittaria species as a remedy for indigestion. The Cherokee used an infusion of leaves to bathe feverish babies, with one sip given orally. The Iroquois used it for rheumatism, a dermatological aid, and a laxative. The Iroquois used it as a ceremonial blessing when they began planting corn. Wildlife: Tubers are planted as an wildlife food. Ducks eat the small, flat seeds of arrowheads, but the tubers are the most valuable to wildlife. Muskrat and porcupine are known to eat the tubers. Swans, geese, wood ducks, blue-winged teal, lesser and greater scaup, ruddy duck, ring necked duck, pintail, mallard, mottled duck, gadwall, canvasback, black duck and king rail are known to eat arrowhead seeds and tubers. For wildlife use, the tubers of Sagittaria latifolia are often too large and too deeply buried to be useful to ducks (Martin 1951). Plant Materials <http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov/> Plant Fact Sheet/Guide Coordination Page <http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov/intranet/pfs.html> National Plant Data Center <http://npdc.usda.gov>

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status and wetland indicator values, , Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Sagittaria viscosa C. Mohr.

Description

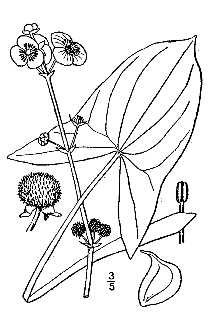

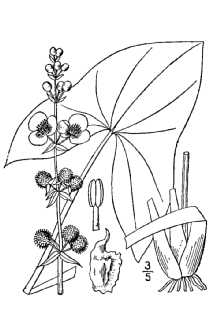

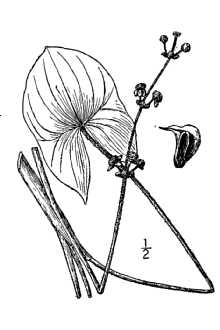

General: Arrowhead Family (Alismataceae). Both Sagittaria latifolia and Sagittaria cuneata are aquatic plants growing in swampy ground or standing water in ponds, lakes, stream edges, and ditches (Hickman 1993). Both species have white or bluish tubers, which are edible. The leaves are sagittate, with leaf blades are either erect or floating on the surface of the water. S. cuneata leaf blades are smaller, from 515 cm, and the lower lobes of emergent leaf blades are less than the terminal lobe. In S. latifolia, leaf blades are from 6-30 cm, and the lower lobes of the emergent leaf blade are approximately equal to the terminal lobe. The inflorescence is simple or branching, often with the lower flowers pistillate and the upper ones staminate. The flowers are white, with three white petals and 3 sepals. Stamens are numerous and bright yellow. The pistils are numerous, spirally arranged on the receptacle. The fruit is an achene and is greenish colored. A diagnostic feature distinguishing the two species is the beak on the fruit of S. cuneata is ascending to erect and <0.5 mm; the beak on the fruit of S. latifolia is spreading and 1-2 mm.

Distribution

For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Sagittaria species are obligate wetland plants found in marshes and wetlands throughout temperate North America. The ranges of S. cuneata and S. latifolia overlap. S. latifolia is found from central and southern British Columbia to Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, south to California and into South America. In California, S. latifolia is confined to lower elevations <1500 m. Sagittaria species grow in ponds, slow streams, ditches and freshwater wetlands.

Establishment

Sagittaria species may be planted from bare root stock, by transplanting the tubers, and by seeding directly into wetland soil. Live plant transplants or transplanting tubers are preferred revegetation methods where there is moving water. It takes two years for seed to germinate; planting bare root stock or tubers gives faster revegetation results. Live Plant Collections: No more than 1/4 of the plants in an area should be collected. If no more than 0.09 m² (1 ft²) are removed from a 0.4 m2 (4 ft2) area, the plants will grow back into the hole in one good growing season. A depth of 15 cm (6 in) is sufficiently deep for digging plugs. This will leave enough plants and rhizomes to grow back during the growing season. Wild plants should be collected after the leaves begin to emerge in the spring until the first frost. The plants can be pulled up easily from wet soil. When collecting wild plants, rinse roots gently. Leaves and stems can be clipped from 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 inches); this allows the plant to allocate more energy into root production. The roots should always remain moist or in water until planted. Plants should be transported and stored in a cool location prior to planting. Water depth should be 0 to 6" and the soils should be wet. Sagittaria grows prolifically around ponds or wetlands in shallow water. Plug spacing of 25-30 cm will fill in within one growing season. Soil should be kept saturated, with approximately 1/2" of water over the surface of the soil after planting. If water is low in nutrients (oligotrophic), fertilization will speed biomass production and revegetation. Many surface waters are already rich in nutrients (eutrophic), and fertilization is not necessary. Indian potatoes transplant success may be greater with the tubers than with bare root stock. The little underground potatoes can be separated from the parent plants with a rake, hoe, or shovel. In unconsolidated soils, the tubers can be pulled up by hand by searching around the roots of the plant. After collecting, the Sagittaria potatoes should be kept moist and cool, and stored in peat moss. Potatoes are then planted in shallow water, in the same conditions as described above for the whole plants. Potatoes should be collected and planted when plants are dormant, in the fall, winter and early spring. Seed Germination: Seeds of Sagittaria species take two years to germinate, because they have a double dormancy requiring cold then warm then cold temperatures. Temperature has a multiple role in the regulation of timing of germination. Dormant seeds become non-dormant only at specific temperatures, non-dormant seeds have specific temperature requirements for germination, and non-dormant seeds of some species are induced into dormancy by certain temperatures. Once Sagittaria seeds germinate, they have fairly high viability. Procedures for growing Sagittaria seeds in the greenhouse have not been developed at this time. Sagittaria seeds can be planted directly in wetlands or ponds. Prepare the area by creating a washboard in shallow water, at mudflat consistency. Seeds should then be scattered on the surface of the soil, as the seeds need sunlight to germinate well. Light and temperature in natural conditions will promote seed germination, and in two years Sagittaria plants will emerge.

Management

Hydrology is the most important factor in determining wetland type, revegetation success, and wetland function and value. Changes in water levels influence species composition, structure, and distribution of plant communities. Water management is absolutely critical during plant establishment, and remains crucial through the life of the wetland for proper community management. Sagittaria species require moist soils to standing water for successful revegetation. We have no record of specific traditional resource management techniques other than anecdotal information of the use of fire to keep dense tule marshes open, which provided an opportunity for colonization and spread of Sagittaria species. The harvest of arrowhead was usually made in late summer as the stems and leaves were dying (and usually when the water table was lower) (Balls 1962). Cultivars, Improved and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Available from native plant nurseries specializing in aquatic plants. Contact your local Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly Soil

Conservation

Service) office for more information. Look in the phone book under ”United States Government.” The Natural Resources Conservation Service will be listed under the subheading “Department of Agriculture.”

References

Angier, B. 1974. Field guide to edible wild plants. Stackpole Books. 255 pp. Barrett, S.A. & E.W. Gifford 1933. Miwok caterial culture Indian life of the Yosemite region. Yosemite Association. Yosemite National Parks, California. 388 pp. Clarke, C.B. 1977. Edible and useful plants of California. University of California Press. 280 pp. Densmore, F. 1974. How Indians use wild plants for food, medicine and crafts. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, New York. 397 pp. Fowler, C.S. 1992. In the shadow of Fox Peak. An ethnography of the cattail-eater Northern Paiute people of Stillwater Marsh. Cultural Resource Series #5. USDI, FWS, Stillwater National

Wildlife

Refuge. 264 pp. Gilmore, M.R. 1977. Uses of plants by the Indians of the Missouri River region. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. 125 pp. Goodrich, J., C. Lawson, & V.P. Lawson 1980. Kashaya Pomo plants. Heyday Books, Berkeley, California. 171 pp. Harrington, H.D. 1972. Western edible wild plants. The University of New Mexico Press. 156 pp. Hedrick, U.P. 1972. Sturtevant's edible plants of the world. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, New York. 686 pp. Hickman, James C. (ed.) 1993. The Jepson manual. Higher plants of California. University of California Press. 1400 pp. Hoag, J.C. & M.E. Sellers 1995. Use of greenhouse propagated wetland plants versus live transplants to vegetate constructed or created wetlands. Interagency Riparian/Wetland Plant Development Project, USDA, NRCS, Plant Materials Center, Aberdeen, Idaho. Hoag, J.C. & M.E. Sellers 1994. Seed and live transplant collection procedures for 7 wetland plant species. Interagency Riparian/Wetland Plant Development Project, USDA, NRCS, Plant Materials Center, Aberdeen, Idaho. Kuhnlein, H.V. & N.J. Turner 1991. Traditional plant foods of Canadian indigenous p eoples. Nutrition, botany and use. Gordon and Breach Science Publishers. 633 pp. Martin, A.C., H.S. Zim, & A.L. Nelson 1951. American wildlife and plants: A guide to wildlife food habits. Dover Publications, Inc. New York. 500 pp. Mason, H.L. 1957. A flora of the marshes of California. University of California Press. 878 pp. Mayer, K.E. & W.F. Laudenslayer Jr., eds. 1988. A guide to wildlife habitats of California. USDA Forest Service, California Department of Fish and Game, PG&E. Moerman, D.E. 1986. Medicinal plants of native America. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology. Technical Reports, Number 19. 534 pp. Peterson, L.A. 1977. A field guide to edible wild plant. Eastern and Central North America. Houghton Mifflin Company. 330 pp. Strike, S.S. 1994. Ethnobotany of the California Indians. Volume 2. Aboriginal Uses of California's Indigenous Plants. Koeltz Scientific Books USA/Germany. 210 pp. USDA, NRCS 1999. The PLANTS database. National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. <http://plants.usda.gov>. Version: 05apr1999.

Fact Sheet

Alternate Names

wapato, broadleaf arrowhead

Uses

This is a multipurpose emergent plant, however the greatest value this species offers is as food and cover for aquatic animal life. The seed and tubers of duck potato are readily consumed by waterfowl, songbirds, wading birds, muskrats, and beaver. The emergent foliage of this species provides cover to the same animals with the addition of fish and aquatic insects. During the growing season notable amounts of nutrients and metals are extracted by Sagittaria latifolia from sediments and water. Turbidity and wave energy is reduced by adequately stocked and healthy stands.

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e,g, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Sagittaria viscosa C. Mohr., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values),

Description

Duck potato is a highly rhizomatous perennial broadleaf emergent capable of attaining heights of 4 feet. The terminal hastate or sagittate leaves are 4 to 12 inches long and acute. Each leaf lobe has an equally distinct vein radiating to it from the leaf base. Vegetative production peaks in July, but by mid fall the emergent plant parts annually die back to the root crown. Prior to the annual die back, nutrients and carbohydrates are translocated to subterranean tubers (root storage organs). Duck potato exhibits both dioecious and moenecious reproductive character in its northern and southern ranges respectfully. Between July and September one or two tapering cylindrical flowering stalks (scapes) emerge holding 2 to 15 whorls of white, three petaled flowers with yellow reproductive parts. Each stalk is taller than the leaves. From August to October round clusters of seed (achenes) develop; with yields up to 20,000 viable achenes produced per plant. Each achene contains a flattened ovate green nutlet. Robert H. Mohlenbrock USDA NRCS 1992 Western Wetland Flora @ USDA NRCS PLANTS

Adaptation and Distribution

Distribution

Distribution

Duck potato has a native range which extends from New Brunswick to British Columbia, south to Florida, California and Mexico. This broadleaf emergent thrives in finely textured unconsolidated organic and silty wet soils. Such conditions are typically found in marshes, swamps, forested seeps, ditches, and in the shallows of streams, lakes and ponds. Duck potato thrives in fresh water 6 to 12 inches deep, full sun exposure, with pH ranging from 6.0 to 6.5, but is tolerant of less adequate conditions. For a current distribution map, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Website.

Establishment

Duck potato can be successfully established vegetatively, with tubers, bare-root or potted stock. As a general rule tubers should be placed on sites with less than one foot of permanent inundation, while the leaves of transplants should never be submerged. For large plantings tubers are most efficiently used, but on critical sites the use of bare-rooted and potted stock is more reliable. A single plant can annually yield up to 40 tubers, with each tuber capable of vegetatively producing 3 to 5 planting units. Site quality will dictate plant spacing. Under ideal site conditions plants can be spread up to 6 feet apart and still attain stand closure within one growing season. On degraded or critical sites it is advisable to reduce plant spacing to 1 to 2 feet. Utilizing seed in greenhouse and nursery production is reliable and highly recommended to maintain genetic diversity. Field seeding techniques have not been refined to attain predictable results. The achenes are easily harvested, cleaned, and broadcast sown. Prior to spring sowing, the seeds need a three month moist stratification treatment. Sow on to well worked, saturated soils. Germination occurs under direct sunlight with temperatures ranging from 80° to 90° F. Read about Civil Rights at the Natural Resources Convervation Service.

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | -33 |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | No |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | High |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | High |

| Cold Stratification Required | No |

| Drought Tolerance | None |

| Fertility Requirement | Low |

| Fire Tolerance | None |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 95 |

| Hedge Tolerance | None |

| Moisture Use | High |

| pH, Maximum | 8.9 |

| pH, Minimum | 4.7 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 50 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 14 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 18 |

| Salinity Tolerance | None |

| Shade Tolerance | Intolerant |

Morphology/Physiology

| After Harvest Regrowth Rate | Slow |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | None |

| Resprout Ability | No |

| Shape and Orientation | Erect |

| Active Growth Period | Spring |

| Bloat | None |

| Coppice Potential | No |

| Fall Conspicuous | No |

| Fire Resistant | No |

| Flower Color | Yellow |

| Flower Conspicuous | Yes |

| Foliage Color | Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Moderate |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Porous |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | No |

| Growth Form | Bunch |

| Growth Rate | Moderate |

| Height, Mature (feet) | 4.9 |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Leaf Retention | No |

| Lifespan | Moderate |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Foliage Texture | Medium |

Reproduction

| Propagated by Cuttings | No |

|---|---|

| Propagated by Seed | Yes |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | No |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Fruit/Seed Period End | Summer |

| Seed per Pound | 67000 |

| Seed Spread Rate | Moderate |

| Small Grain | No |

| Vegetative Spread Rate | None |

| Propagated by Container | No |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | No |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | No |

| Fruit/Seed Period Begin | Spring |

| Fruit/Seed Abundance | Medium |

| Commercial Availability | Routinely Available |

| Bloom Period | Late Spring |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | No |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | No |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | No |

| Palatable Browse Animal | High |

| Nursery Stock Product | No |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | No |

| Fodder Product | No |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | No |