Potamogeton pectinatus L.

Scientific Name: Potamogeton pectinatus L.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | POPE6 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herb |

| Native Locations | POPE6 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Previously known as Potomogeton pectinatus and Stuckenia pectinatus, the currently accepted name is Stuckenia pectinata. Coleogeton pectinatus; Potomogeton interruptus; Potomogeton latifolius; Potomogeton flabellatus; Potomogeton columbianus; broadleaf pondweed; duck grass; eelgrass, fennel pondweed; foxtail; Indian grass, old-fashioned bay grass; pondgrass; potato moss; wild celery; fennel-leaved water milfoile; poker grass; pochard grass; string weed

Uses

Wildlife: Waterfowl extensively use and rely on sago pondweed as a food source (Kantrud, 1990). The whole plant can be consumed, and parts are utilized by diving, dabbling, whistling ducks, many types of geese, swans, coots (Kantrud, 1990) and the long-billed dowitcher (Sperry, 1940). Bioremediation and bioindication: May be used to suppress phytoplankton blooms by taking up phosphorus from the water (Stewart and Davies, 1986). May also be used to monitor heavy metal pollution in rivers (Whitton et al., 1981). Erosion control: The wave dampening action of sago pondweed can be used for erosion control of shores and dams (Kantrud, 1990).

Status

Sago pondweed is a threatened plant in New Hampshire. Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Weediness

This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not properly managed. Please consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding its status and use. Weed information is also available from the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov. Please consult the Related Web Sites on the Plant Profile for this species for further information. Sago pondweed is considered a nuisance weed or noxious weed in some waters that are used for recreational purposes (Harrison, 1962; Kantrud, 1990) and irrigation canals (Yeo, 1965; Kantrud, 1990).

Description

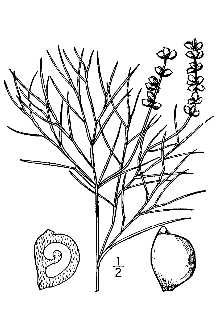

General: Pondweed Family (Potomogetonaceae). Sago pondweed is an aquatic herbaceous plant up to 1 m tall (Bare, 1979). Sago pondweed is generally completely submersed except the reproductive spike that peaks above the water that flowers June – September (Larson, 1993). It is nearly unbranched at the base, becoming freely branched towards the top (Larson, 1993). The leaves are filiform to threadlike being 2-12 cm long and between 0.2 - 1.5 cm wide, with stipules fused to the blade being up to 2/3 as long as the leaf blade (Bare, 1979; Larson, 1993). The inflorescence is a spike with 2-6 unevenly spaced

Adaptation

Sago pondweed occurs nearly worldwide and is found submerged in semi-permanent to permanently flooded areas where the water is less than 2.5 m deep and the flow is less than 1 m/s (Kantrud, 1990). It can be found from sea level to almost 4,900 m above sea level (Ascherson and Graebener, 1907, citied in Yeo, 1965 and Kantrud, 1990). Sago pondweed can grow in nearly all bottom substrates and can tolerate high salinity, pH, and alkaline water (Kantrud, 1990). It does not grow well in waters with high turbidity (Kantrud, 1990).

Establishment

Sago pondweed can be cultured in liquid media for experimental purposes from druplets, turions, rhizomes, leafy tops, or cuttings. This method eliminates uncontrolled variables that can be introduced from the substrate or soil in which sago pondweed would normally be grown (Kantrud, 1990). Druplets can be stored in wet or dry conditions. However, to break the dormancy it is best to store in water at temperatures just above freezing when using plant materials that were collected in temperate regions (Kantrud, 1990). McAtee (1911) suggested planting druplets immediately after harvest or removal from storage, but Van Wijk (1983) indicated that the best germination (about 40%) could be accomplished by drying druplets for three months in sediment, then ripening them for 14 months in tap water at room temperature, and then placing them in freshwater. Turions can be harvested and stored for a period of up to four years, if dipped in paraffin (Yeo, 1965). Turions can also be stored in water at low temperatures or packed in layers of straw or moss (Kantrud, 1990).

Management

Managers have tried to manipulate populations of sago pondweed for use by waterfowl and wildlife by adjusting the water levels. However, results from these trials are variable and depend on water chemistry, water levels, geography, and other macrophyte competitors (Kantrud, 1990). In some cases, declines in populations have been achieved by partially dewatering of the pools. In other instances, an increase in sago pondweed was observed by partially or fully dewatering the pools (Kantrud, 1990).

Pests and Potential Problems

Although not conclusive, there are bacteria and fungi that may cause diseases in sago pondweed and could be responsible for a decline in sago populations or deformities of the plants. The specific species that have been implicated include Rhizoctonia solani, Tetramyxa parasitica, Pythium spp., Curvularia sp., Phoma sp., Pullularia pullulans, and Hyaloflorae sp. While these species have been implicated, it has not been concluded that these pathogens are the cause of the decline or that sago pondweed is necessarily susceptible to these diseases (Kantrud, 1990).

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

Sago pondweed has been considered a noxious weed in waters used for recreational purposes and irrigation. Sago can physically obstruct recreational activities and water flow. Sago may also become a substrate that allows nuisance algae to attach. Sago may also cause very low levels of O2 in streams used to move sewage effluent (Madsen et al., 1988). Dense formations of sago beds may also limit movement of predator fish and inhibit fishing (Engel, 1984). It has also been documented that sago pondweed can clog water intake ports at power plants (Peltier and Welch, 1969).

Control

Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Some of the chemicals mentioned may not be safe or legal for use in aquatic environments. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Chemical: Many herbicides and chemicals have been used to attempt to control growth or numbers of sago pondweed. For specific information on the rates and use of each chemical mentioned please refer to the associated reference and the label instructions. Commercial fertilizers have been recommended to increase phytoplankton in water thus reducing water clarity and preventing sago pondweed invasion (Walker, 1959; Kantrud, 1990). Established stands of sago pondweed have been controlled by using 2,4D granules, silvex, and sodium arsenite (Davison et al., 1962; Kantrud 1990). Copper sulfate, diquat, fenac, dichlobenil, naptalum, morflurazon, aquathol-K, aquizine, ortho diquat, 2,4D butoxethanol ester, atrazine, glycophosphate, triazine, carbofuran, and alachlor have been used to control or inhibit sago pondweed targeting various parts of the plant (Kantrud, 1990). Physical and Biological: Mechanical and physical removal and control of sago pondweed by using rakes, cables, mechanical harvesters, and light exclusion have been used but have had limited or no success and are not economically feasible (Kantrud, 1990; Mitzner, 1978; Gangstad, 1976; Mayhew and Runkel, 1962; Engel, 1984). Using other vascular plants to prevent the establishment of sago pondweed has been suggested by Yeo (1976) and Madsen (1986). Animal control of sago pondweed has been tried using the burrowing chrysomelid beetle, Haemonia appendiculata (Donaciinae) (Grillas, 1988; Kantrud, 1990), and the grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella (Kantrud, 1990). However, using these animals did not obtain the control of sago pondweed that was desired.

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Druplets can be broadcast seeded into shallow water, less than 2 meters, however, the best establishments have been by imbedding druplets, turions, or plant tops in clay and dropping them from boats in the spring (Kantrud, 1990), A planting rate of 3,000 plant parts per hectare is recommended and stands are not likely to be very robust until the second season after root systems have developed (Kantrud, 1990), Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Potamogeton pectinatus L.., Sago pondweed does not compete well with other macrophyte competitors such as Myriophyllum, Ceratophyllum, Ruppia, and Chara, Water chemistry should also be monitored, as sago pondweed does best in waters with salinity between 5-15 g/L, Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Theses plant materials are somewhat readily available from commercial sources, There are no known cultivars, improved, or selected materials at this time,

References

Ascherson, P., and P. Grabener. 1907. Potamogetonaceae das Pflanzenreich. 4:133. Bare, J.E. 1979. Wildflowers and Weeds of Kansas. The Regents Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. Coetzer, A.H. 1987. Succession in zooplankton and hydrophytes of a seasonal water on the west coast of South Africa. Hydrobiologia 148: 193-210. Davison, V.E., J.M. Lawrence, and L.V. Compton. 1962. Waterweed control on farms and ranches. U.S. Dep. Agric. Farmers’ Bull. 2181 Engel, S. 1984. Restructuring littoral zones: a different approach to an old problem. Proc. N. Am. Lake Manage. Soc. 3:463-466. Gangstad, E.O. 1986. Freshwater vegetation management. Thomas Publishers, Fresno, Calif. Grillas, P. 1988. Haemonia appendiculata Panzer (Chrysomelidae, Donaciinae) and its impact on Potamogeton pectinatus L. and Myriophyllum spicatum L. beds in the Camargure (S. France). Aquat. Bot. 31:347-353. Harrison, A.D. 1962. Hydrobiological studies on alkaline and acid still water in the Western Cape Province. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 36: 213-243. Kantrud, H.A. 1990. Sago pondweed (Potamogeton pectinatus L.): A literature review. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Resource Publication 176. Washington D.C. Larson, Gary E. 1993. Aquatic and wetland vascular plants of the northern Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-238. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. Jamestown, ND: Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online. http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/plants/vascplnt/index.htm (Version 02FEB99). Madsen, J.D. 1986. The production and physiological ecology of the submerged aquatic macrophyte community in Badfish Creek, Wisconsin. Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison. Madsen, J.D., M.S. Adams, and P. Ruffier. 1988. Harvest as a control for sago pondweed (Potamogeton pectinatus L.) in Badfish Creek, Wisconsin: frequency, efficiency and its impact on stream community oxygen metabolism. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 26:20-25. Mayhew, J.K., and S.T. Runkel. 1962. The control of nuisance aquatic vegetation with black polyethylene plastic. Iowa Acad. Sci. 69:302. McAtee, W.L. 1911. Three important wild-duck foods. U.S Bur. Biol. Surv. Circ. 81. Mitzner, L. 1978. Evaluation of biological control of nuisance aquatic vegetation by grass carp. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 107:135-145. Peltier, W.H., and E.B. Welch. 1969. Factors affecting growth of rooted aquatics in a river. Weed Sci. 17:412-416. Sperry, C.C. 1940. Food habits of a group of shorebirds: woodcock, snipe, knot and dowitcher. U.S. Bur. Biol. Surv., Wildl. Res. Bull. 1. Stewart, B.A.. and B.R. Davies. 1986. Effects of macrophyte harvesting on invertebrates associated with Potamogeton pectinatus L. in the Marina Da Gama, Zandvlei, Western Cape. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 46, Part 1: 35-50. Van Wijk, R.J. 1983. Life-cycles and reproductive strategies of Potamogeton pectinatus L. in the Netherlands and the Camargue (France). Pages 317-321 in Proceedings of the International Symposuium on Aquatic Macrophytes, 18-23. Sept. 1983. Nijmegan, Netherlands. Walker, C.R. 1959. Control of certain aquatic weeds in Missouri farm ponds. Weeds 7:310-316. Whitton, B.A., P.J. Say, and J.D. Wehr. 1981. Use of plants to monitor heavy metals in rivers. Pages 135-145 in P.J. Say and B.A. Whitton, eds. Heavy metals in northern England. Environmental and biological aspects. Botany Department, University of Durham. Yeo, R.R. 1965. Life History of sago pondweed. Weeds 13: 314-321. Yeo, R.R. 1976. Naturally occurring antagonistic relationships among aquatic plants that may be useful in their management. Pages 290-293 in T.E. Freeman, ed. Proceedings of the IV International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, Gainesville, Florida.

Fact Sheet

Alternate Names

Previously known as Potamogeton pectinatus and Stuckenia pectinatus, the currently accepted name is Stuckenia pectinata. Coleogeton pectinatus; Potamogeton interruptus; Potamogeton latifolius; Potamogeton flabellatus; Potamogeton columbianus; broadleaf pondweed; duck grass; eelgrass, fennel pondweed; foxtail; Indian grass, old-fashioned bay grass; pondgrass; potato moss; wild celery; fennel-leaved water milfoile; poker grass; pochard grass; string weed

Uses

Wildlife: Waterfowl extensively use and rely on sago pondweed as a food source. The whole plant can be consumed, and parts are utilized by diving, dabbling, whistling ducks, many types of geese, swans, coots and the long-billed dowitchers. Bioremediation and bioindication: May be used to suppress phytoplankton blooms by taking up phosphorus from the water and to monitor heavy metal pollution in rivers. Erosion control: The wave dampening action of sago pondweed can be used for erosion control of shores and dams.

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Sago pondweed is an obligate wetland species.

Weediness

This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not properly managed. Please consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding its status and use. Weed information is also available from the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov. Please consult the Related Web Sites on the Plant Profile for this species for further information. Sago pondweed is considered a nuisance weed or noxious weed in some waters that are used for recreational purposes and in irrigation canals.

Description and Adaptation

Adaptation , Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Potamogeton pectinatus L..

Adaptation

General: Pondweed Family (Potamogetonaceae). Sago pondweed is an aquatic herbaceous plant up to 3 feet tall. Sago pondweed is generally completely submersed except the reproductive stalk that peaks above the water that flowers June – September. It is nearly un-branched at the base, becoming freely branched towards the top. The leaves are ¾ -4.5 inches long and up to ½ inch wide. The flower stalk can be up to 2 inches long. Fruits are yellowish to brown. Sago pondweed occurs nearly worldwide and is found submerged in semi-permanent to permanently flooded areas where the water is less than 8 feet deep. It can be found from sea level to almost 16,000 feet above sea level. Sago pondweed can grow in nearly all bottom

Establishment

Sago pondweed can be cultured in liquid media for experimental purposes from drupelets, turions, rhizomes, leafy tops, or cuttings. Drupelets can be stored in wet or dry conditions. Turions can be harvested and stored for a period of up to four years, if dipped in paraffin. Turions can also be stored in water at low temperatures or packed in layers of straw or moss.

Management

Managers have tried to manipulate populations of sago pondweed for use by waterfowl and wildlife by adjusting the water levels. However, results from these trials are variable and depend on water chemistry, water levels, geography, and other plant competitors.

Pests and Potential Problems

Although not conclusive, there are bacteria and fungi that may cause diseases in sago pondweed and could be responsible for a decline in sago populations or deformities of the plants.

Environmental Concerns

Sago pondweed has been considered a noxious weed in waters used for recreational purposes and irrigation. Dense formations of sago beds may also limit movement of predator fish and inhibit fishing.

Control

Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Many chemical, biological, and physical methods have been used to attempt to control growth or numbers of sago pondweed. Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Theses plant materials are somewhat readily available from commercial sources. There are no known cultivars, improved, or selected materials at this time.

Prepared By

P. Allen Casey, USDA NRCS Plant Materials Center, Manhattan, Kansas

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Moisture Use | High |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | High |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | High |

| Cold Stratification Required | No |

| Drought Tolerance | None |

| Fertility Requirement | Medium |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 125 |

| Hedge Tolerance | None |

| pH, Maximum | 8.5 |

| pH, Minimum | 6.0 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Maxim | 4800 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Minim | 3450 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 60 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 12 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 0 |

| Salinity Tolerance | Medium |

| Shade Tolerance | Intolerant |

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | -38 |

Morphology/Physiology

| Bloat | None |

|---|---|

| Shape and Orientation | Decumbent |

| Toxicity | None |

| Active Growth Period | Summer |

| Coppice Potential | No |

| Fall Conspicuous | No |

| Fire Resistant | No |

| Flower Color | Green |

| Flower Conspicuous | No |

| Foliage Color | Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Porous |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Porous |

| Foliage Texture | Fine |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | No |

| Growth Form | Single Crown |

| Growth Rate | Slow |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Leaf Retention | No |

| Lifespan | Moderate |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Resprout Ability | No |

| Fruit/Seed Color | Blue |

Reproduction

| Propagated by Cuttings | No |

|---|---|

| Propagated by Seed | Yes |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | Yes |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Seed Spread Rate | Rapid |

| Fruit/Seed Period Begin | Spring |

| Seedling Vigor | Medium |

| Small Grain | No |

| Vegetative Spread Rate | None |

| Propagated by Container | No |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | Yes |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | No |

| Fruit/Seed Period End | Fall |

| Fruit/Seed Abundance | Medium |

| Commercial Availability | Routinely Available |

| Bloom Period | Mid Spring |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | No |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | No |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | No |

| Nursery Stock Product | No |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | No |

| Fodder Product | No |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | No |