Jacobaea vulgaris Gaertn.

Scientific Name: Jacobaea vulgaris Gaertn.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | JAVU |

| Group | Dicot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herb |

| Native Locations | JAVU |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

staggerwort, stinking willie.

Uses

Tansy ragwort exceeds the 1975 U.S. National Research Council protein and digestibility requirements for sheep for which it has been suggested as good summer feed. It is a good bio-monitor of iron, manganese and zinc in atmospheric pollutants.

Status

Tansy ragwort is a non-native, invasive terrestrial forb listed as noxious, prohibited, or banned in nine states.

Weediness

This plant may be weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not properly managed. Consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding its status and use. Additional weed information is available from the PLANTS Web site at plants.usda.gov. Consult other related web sites on the Plant Profile for this species for further information.

Description

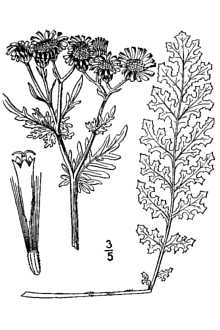

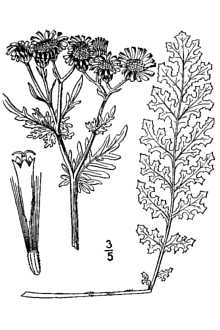

Tansy ragwort is a winter annual, biennial, or short-lived perennial commonly growing between 8-36 inches (20-80 centimeters) tall, but sometimes to heights greater than 6 feet (175-200 centimeters) under optimal conditions. Rigid stems grow singly or in groups from an upright caudex with only the upper half of the stems branching at the inflorescence. Tansy ragwort additionally perennates via fragments of the numerous (50-100/crown) soft, fleshy roots that grow primarily horizontally and penetrate the soil to a maximum depth of 12 inches (30 centimeters). Rosettes, either seedling or root bud in origin, are formed from distinctive stalked basal leaves 2.7-7.9 inches (7-20 centimeters) long, deeply and pinnately lobed with ovate, obovate, or narrow coarsely-toothed segments. Leaves are either glabrous or with loose wooly down on the underside, especially during early development. Rosette leaves generally die back at or before flowering. Stem leaves are deeply bi- or tri-pinnatifid, arranged alternately on the stem and are reduced in size higher on the stem. Middle and upper stem leaves lack a petiole and slightly clasp the stem. Bright yellow, showy flowers arise only on the pedicel ends; outer pedicels are progressively longer than inner pedicels and form flat- or round-topped, dense and compact corymbs. Capitula 12-25 millimeters in diameter and numbering 20-60 per corymb have 13 dark-tipped bracts 3-4 millimeters long, and are composed of both ray and disc florets. There are 13 achene producing ray florets with rays 8-2 millimeters long. Disc florets are numerous and produce both pollen and achenes. The number of capitula and achenes produced per plant is highly variable. Single seeds are contained within each achene; achenes produced from ray florets shed their pappus, are glabrous, and have a thick pericarp, whereas achenes produced from disc florets retain their pappus, are pubescent with short hairs (trichomes) along prominent ribs and are lighter in weight than ray achenes. The pappus, composed of numerous white 'hairs' 6 millimeters in length, is attached to the top of the achene; its resemblance to a white beard explains the origin of the genus name, Senecio, derived from the Latin senex for "old" or "old man". Tansy ragwort can be distinguished from native Senecio species by its comparatively larger size and exaggerated pattern of leaf dissection. Although tansy ragwort superficially resembles common tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), it differs significantly in flower composition, producing capitula with both ray and disc florets whereas common tansy flowers are composed solely of disc florets.

Distribution

For current distribution, consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site.

Habitat

Tansy ragwort tolerates a wide range of habitats and environmental conditions but is generally found on mesic sites with commonly cool, wet, cloudy weather. It grows on many soil types but usually on lighter, well-drained loamy to sandy soils. It normally does not grow where there is a high water table or on highly acidic soils. In Europe it naturally occurs in sand dune, woodland, and grassland communities. In North America it is found in pastures, forest clearings, and waste places and is often associated with Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), common St. Johnswort (Hypericum perforatum) and yellow toadflax (Linaria vulgaris).

Life History

Tansy ragwort is typically a biennial plant: it reproduces for the most part by seed; it overwinters in the seed or rosette stage; and it passes through the first growing season in the vegetative rosette stage before becoming reproductively mature. However, because both the root and the caudex of this species have the capacity to form perennating buds under environmental or mechanical stress, tansy ragwort has the vegetative regenerative capacity of a perennial. A study of 179 plants in Australia found 2% were annuals, 45% biennials, and 39% were perennials. A separate study in England found 8% of the plants were annuals, 39% were biennials, and 53% were perennials. Tansy ragwort has been observed as a true perennial by continuing to grow after flowering, particularly after disturbance. An Oregon study reported 20% of the tansy ragwort plants in a population were true perennials. Tansy ragwort has four distinct life history stages: seeds, seedlings, rosettes, and flowering plants. The viability of a tansy ragwort seed crop is about 80%. The seeds have no mechanisms of innate dormancy other than the relatively thick pericarp on ray floret achenes which is believed to delay germination by a few days. The maximum potential for germination is reached when achenes leave the flowerhead: however, experimentation showed this potential did not significantly decrease after three years of storage under field conditions. Most seed germinates in the late summer or early autumn, but seeds lying dormant throughout the winter will germinate at the beginning of the growing season in the spring. Ideal temperatures for germination range between 41-86o F (5-30o C). Soil moisture influences germination: at any given temperature an increase in soil moisture increases germination and the optimum temperature for germination changes as soil moisture changes. Vegetative cover may inhibit germination and frost, drought, or burial may induce dormancy. Seed buried in soil deeper than 0.75 inch (2 centimeters) remain dormant. Light is required for germination. Studies showed 24% of seeds buried for six years maintained their viability. Also, seeds buried up to 2 centimeters deep had a higher germination rate than seeds left on the soil surface, most likely because moisture is consistently greater below the soil surface than on the surface. Seeds subjected to drought or cold temperature shock had delayed germination; the longer the shock, the longer the delay. Seedling establishment and survival are variable, the largest determinant of survival being the amount of vegetative cover. In experimental garden plots two months after seeding tansy ragwort, no seedlings survived in plots with long grass or in plots with short but continuous turf, whereas seedling survival was greater in cleared or forest land areas than grassy areas. Grazed pastures on Prince Edward Island, Canada, had about eight times more tansy ragwort plants than non-grazed pastures. Once established, seedlings form flattened rosettes that are effective competitors. The large rosette leaves are able to cover neighboring plants thereby suppressing their growth. When the rosette leaves die, sites are opened for tansy ragwort seed germination. One study found seedling establishment was over four times higher on sites opened by dying rosettes than on sites in surrounding vegetation. Alkaloids produced by rosettes may have the allelopathic effect of suppressing other plants. Rosette leaves die when plants flower. Plants typically flower during the second year of growth. Flowering has been reported to begin as early as June and to last as late as mid-November. It is believed rosettes must achieve some minimum size before flowering can begin, and the probability of flowering increases as rosette size increases. Floral expansion is rapid and florets are receptive to pollination as soon as the floret is fully expanded. Hymenopteran (bee/wasp) and dipteran (fly) insect species are the primary pollinators of tansy ragwort. Seed disperses throughout the fall. Rosettes that do not flower continue to grow into the fall accumulating storage carbohydrate important for winter survival. Carbohydrate content of the plant is highest going into winter.

Establishment

Tansy ragwort establishes from seed and root fragments.

Management

See

Control

Pests and Potential Problems

See Environmental Concerns.

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

Tansy ragwort can reduce forage yields by as much as 50% in pastures, Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are present in all plant parts, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Jacobaea vulgaris Gaertn.., Cattle, deer, horses and goats consuming either growing plants or tansy ragwort in silage and hay store these alkaloids in their liver, Even if symptoms are not evident or are minor in nature, the cumulative storage of alkaloids can result in reduced weight gain, liver degradation, reduced butterfat content of milk, and sudden death in apparently healthy animals, Alkaloids in tansy ragwort pollen also taint honey, making it bitter, off-color and unmarketable,

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Not applicable. Control Contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best for control in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Tansy ragwort can be controlled using auxinic herbicides (mimics of auxin, a naturally-occurring plant growth regulator). The best timing of application is when tansy ragwort is actively growing in the rosette stage either in the spring or mid-fall. Herbicides are less effective after plants have bolted to produce flowers. In most cases reapplication of herbicide or integration with other control methods will be required for sustained population reductions. The amine, low-volatile ester, or emulsifiable acid formulations of 2,4-D are effective when applied at two pounds acid equivalent per acre. Always check the herbicide label to confirm formulation and proper use of the product before applying. When using four pounds acid equivalent per gallon formulation, apply the mixed product at a rate of two quarts per acre. Tansy ragwort is listed on the following herbicide labels at rates in parentheses: picloram (1-2 qt./ac.), aminopyralid (5-7 oz./ac.), metsulfuron (0.5-1 oz./ac. with nonionic surfactant at 0.5%), and chlorsulfuron (1-3 oz./ac. with nonionic surfactant at 0.5% volume to volume). Metsulfuron and chlorsulfuron should not be applied where soil pH is greater than 7.9 because under these conditions chemical breakdown is slow resulting in extended residual activity that increases the risk of off-site movement of the chemical and non-target plant injury. Consult individual herbicide labels for other possible soil pH restrictions. Herbicides are most effective where competitive desired plants are present to fill voids in the plant community following successful tansy ragwort control. However, herbicide injury to non-target desirable broadleaved plants and some grasses should be expected; consult product labels for further information on potential non-target injury. To avoid non-target injury, apply herbicides in the fall after desired plants are dormant for the winter. This tactic is most effective when using herbicides with low residual activity. Always follow label instructions to reduce toxicity or other unintended risks to humans and the environment, and to confirm potential grazing and replanting restrictions. Herbicide treatments typically increase the concentration of water-soluble carbohydrate in tansy ragwort, making it more palatable to livestock and thereby increasing the risk of alkaloid poisoning. Grazing should therefore be deferred for 3-4 weeks after herbicide application. Hand pulling and digging that extracts all of the caudex and fleshy rootstock is an effective method to temporally reduce tansy ragwort on small-scale infestations and scattered plants either as new invaders or those persisting after herbicide treatments. Pulling rosette and flowering plants will reduce seed set. Follow-up management will be needed to eliminate plants regenerating from root fragments or seed. Protective gloves are recommended to be worn as a precautionary measure by anyone handling tansy ragwort. Mowing is not an effective control for tansy ragwort. Rosettes are flat to the ground and may be missed by the mower blade, and when clipped, vegetative reproduction is stimulated. Mowing when plants bolt to flower may temporarily reduce seed production; however, plants will survive to flower again. A dispersal study found achenes dispersed as much as two and a half times farther on mowed sites than where the natural vegetation remained. However, in Switzerland, frequent mowing promoted fast-growing grass species and was associated with reduced occurrence of tansy ragwort. Mowing to maintain vigorous grassland communities may help prevent tansy ragwort invasion. The roots and caudex of tansy ragwort have the ability to regenerate after they are broken by tilling. Therefore, tillage has the potential to spread tansy ragwort and is not recommended by itself. The disturbance of tillage can create a favorable environment for tansy ragwort growth and reproduction by reducing competitive perennial plants. Tillage should be combined with herbicide management and followed by revegetation with desired, competitive plants. Tansy ragwort thrives under mesic conditions and therefore irrigation is not recommended as a control by itself. Where tansy ragwort invades irrigated pastures and hayland, carefully planned irrigation management will stimulate the competitiveness of the forage crop and when combined with nutrient, forage harvest, and grazing management practices and will help prevent the re-establishment of tansy ragwort after other control practices are applied. Tansy ragwort is found on pastures of low to moderate nutrient status in Switzerland, which is part of its native range. A Swiss study found the amount of plant-available nitrogen was one of the most important factors predicting the occurrence of tansy ragwort. The model developed from that study predicted a fivefold reduction in the risk of tansy ragwort occurrence by doubling the application of nitrogen from about 50 lb./ac. to 100 lb./ac. On cultivated pasture and hay meadows, nutrient management is important to maintaining the competitiveness of desired perennial grasses. Nutrient management combined with judicious use of herbicides and crop rotation is recommended where tansy ragwort invades non-native pastures and hay meadows. Fire is reportedly effective in killing reproductive tansy ragwort plants and achenes. Fire is also sometimes used to maintain the vigor and density of grassland communities by burning excess plant litter and possibly increasing soil fertility. Fire can therefore be used as a preventative measure or in combination with other control methods to reduce tansy ragwort populations. On forested sites and clearings, the disturbance caused by fire may create openings favorable to tansy ragwort invasion. The way grazing is managed is an important factor influencing localized presence and distribution of tansy ragwort in its native range. In a Swiss study continuously grazed pasture was 11 times more likely to be infested by tansy ragwort than pasture managed under rotational grazing because the former management regime resulted in more openings in the grass canopy where tansy ragwort could establish. Pasture with greater than 25% uncovered soil had a 40-fold greater risk of tansy ragwort occurrence than pasture with less than 25% bare ground. Prescribed grazing that maintains a continuous grassland community is recommended both for the prevention of tansy ragwort invasion and in pastures where it is already being controlled. Tansy ragwort leaves and flowers exceed the standard protein and digestibility requirements for sheep. In addition, sheep seem to be immune to the plant’s toxic alkaloids, and are willing grazers of young plants. In New Zealand, intensive sheep grazing is the predominant management approach for tansy ragwort; the weed generally does not occur where sheep are regularly stocked. In an Oregon grazing study, tansy ragwort seed production was prevented and plant mortality was attributed to sheep grazing in the summer following cattle grazing in the spring. A separate study found tansy ragwort plants subjected to 75% defoliation were able to compensate fully five months after treatment when grown without competition. When grown in competition with Richardson’s fescue (Festuca rubra), there was no re-growth after 75% defoliation. These studies suggest sheep grazing is effective in controlling tansy ragwort where it grows in a competitive grassland community. Biological control of tansy ragwort in the U.S. was initiated in 1959 with the California release of the cinnabar moth, Tyria jacobaeae L. (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae). This agent is now well-established in California, Oregon, Washington, northern Idaho and northwestern Montana. The cinnabar moth flourishes in lower elevation (below 3,000 feet/900 meters) open canopy areas with warm, sunny summers and large, high-density infestations of tansy ragwort. Adult moths are 0.60-0.88 inch (15-22 millimeters) long with a wingspan of 1.08-1.40 inches (27-35 millimeters) and have a distinctive appearance: the black forewing is marked by a few irregularly-shaped crimson spots and a crimson line along the outer edge of the wing while the hind wing is entirely crimson. Cinnabar moth. Image: Eric Coombs, Oregon Department of Agriculture. Available at Bugwood.org Cinnabar moths typically emerge by late spring, mate and finish depositing eggs by mid-summer. Moths can be roused into flight during daylight hours when host vegetation is disturbed. Eggs are laid on the underside of rosette leaves in small groups. The eggs hatch after several weeks’ development and emerging larvae begin feeding on foliage closest to the hatch site. The damaging larval stage of this agent is easily recognized by its alternating bands of bright orange and black. Pupation begins in late summer when the fully-grown fifth-instar larvae seek out suitable sites in debris or soil, or under bark; the cinnabar moth overwinters as a 0.80-1.00 inch (20-25 millimeters) long dark reddish-brown pupa. Roving groups (10-30 individuals) of the gregarious larval stage of this agent aggressively feed on the leaves, flowers and apical meristems of bolting tansy ragwort, leaving plants stripped of all foliage. Larval feeding can lead to significant reductions in seed production and stand density, although impact varies considerably. The larval stage of this agent is optimal for redistribution onto uncolonized populations of tansy ragwort. Caterpillars are easily collected by shaking plants over collecting pans (such as kitty litter trays); retain larvae under cool, dry and uncrowded conditions in ventilated (with pin holes) containers provisioned with fresh host plant material for as short a period as possible before releasing. Because endogenous toxic alkaloids sequestered from tansy ragwort are present in both the larval and adult stage of this agent, implications for livestock health and management should be considered when choosing sites for releasing the cinnabar moth. Larval stage of cinnabar moth. Image: Eric Coombs, Oregon Department of Agriculture. Available at Bugwood.org The efficacy of the cinnabar moth alone in controlling tansy ragwort is limited with successful control reported only when larval defoliation was accompanied by favorable environmental factors (frost). Although this agent is highly effective in combination with the ragwort flea beetle, its deployment has been surrounded by controversy. Non-target attack on the exotic weed common groundsel Senecio vulgaris, two native species Senecio triangularis and Packera pseudaurea (formerly Senecio pseudaureus) and the ornamental silver ragwort, Senecio bicolor, have been reported when moth population densities outstrip local tansy ragwort resources. The ragwort seed fly Botanophila seneciella Meade (Diptera: Anthomyiidae) was first introduced in California in 1966 and was the first tansy ragwort agent to become well-established east of the Cascades. Botanophila seneciella was released to additively improve tansy ragwort biocontrol by bolstering the low levels of control realized with the cinnabar moth. Adult flies, 0.20-0.28 inch (5-7 millimeters) in length, emerge in spring and deposit eggs on tansy ragwort flower buds through early summer. The 0.16-0.24 inch (4-6 millimeters) long creamy-white larva tunnels into the flowerhead and throughout the receptacle, eventually moving back up to the seed head. Evidence of infestation by this agent is obvious: larval feeding generally destroys all seed within mined seed heads, and flowers under attack are typically marked by frothy spittle. Ragwort seed fly - adult. Image: Eric Coombs, Oregon Department of Agriculture. Available at Bugwood.org Mature larvae exit host seed heads in late summer to pupate in the soil. The ragwort seed fly overwinters as a dark brown 0.2 inch (5 millimeters) long pupa. Because this agent shares the same habitat preferences as the cinnabar moth, their joint release is often marked by resource competition for favorably located host plants. The seed fly usually loses out because the moth’s phenology allows it to begin ovi-positing earlier so that caterpillars have generally stripped all flowerheads from plants in open canopy areas by the time the seed fly is ready to begin ovi-position. Reproductive success is significantly reduced when resource competition forces the fly to lay eggs on host plants located in moist, shaded areas. This agent has self-distributed comprehensively throughout the Pacific Northwest; redistribution is generally unnecessary but if desired is best accomplished by transplanting fly-infested plants in late spring. The light gold-colored ragwort flea beetle, Longitarsus jacobaeae Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), first introduced to the U.S. in 1969, is now established in Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and California. Intensive foliar feeding by adult flea beetles, termed "shot holing," is a clear indicator of whether or not a tansy ragwort stand has been colonized by this agent. Ragwort flea beetles introduced to the U.S. before 2002 were collected in Italy; the so-called Italian strain of this agent is credited with exceptional control and continued suppression of tansy ragwort infestations west of the Cascades. A Swiss strain of this agent with a completely different phenology than the Italian strain and believed to be better adapted to higher elevations, colder winters and shorter growing seasons typical of tansy ragwort infested areas east of the Cascades was released in Montana in 2002. Adult Italian-strain ragwort flea beetles emerge briefly in spring before returning to the soil to estivate (summer dormancy) until prompted by late summer/early fall rains to begin mating. Eggs laid from October through November produce slender white larvae 0.08-0.16 inch (2-4 millimeters) in length that feed throughout the winter on the host plant roots. Larvae leave the roots in the spring to pupate in the soil. Pupae are white and 0.08-0.16 inch (2-4 millimeters) long. Swiss-strain adult flea beetles emerge from their pupation sites in the soil in late spring to early summer and begin feeding, mating and laying eggs immediately. Development in the eggs of Swiss-strain beetles is delayed through the rest of that summer, fall and winter and does not begin until the following spring. Larvae feed on and in tansy ragwort roots until pupating in the fall. The Swiss strain of the ragwort flea beetle is unique in that it overwinters both in the egg and pupal stage. Adults of both strains are 0.08-0.16 inch (2-4 millimeters) in length with the males approximately 0.04 inch (1 millimeter) shorter than the females. Tansy ragwort rosettes appears to be the most susceptible stage of this weed as significant control is realized from both larval root mining and adult foliar feeding that specifically targets vegetative (non-reproductive) plants. The adult flea of the beetle is best suited to successful collection for redistribution, either by vacuum collection or sweeping, October-November for the Italian strain and mid-summer for the Swiss strain. Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin): Not applicable. References: Bain, J.F. 1991. The biology of Canadian weeds. 96. Senecio jacobaea L. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 71: 127-140. Coombs, E.M., J.K. Clark, G.L. Piper and A.F. Cofrancesco, Jr. (Eds). 2004. Biological Control of Invasive Plants in the United States. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press. 467 pp. Coombs, E.M., H. Radtde, D.L. Isaacson and S.P. Snyder. 1997. Economic and regional benefits from the biological control of tansy ragwort, Senecio jacobaea, in Oregon. Proceedings of the IX International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, pp. 489-494. V.C. Moran and J.H. Hoffmann University of Cape Town. Crawley, M.J. and R. Pattrasudhi. 1988. Interspecific competition between insect herbivores: asymmetric competition between cinnabar moth and the ragwort seed-head fly. Ecological Entomology 13: 243-249. Harper, J.L. and W.A. Wood. 1957. Senecio jacobaea L. Ecology 45: 617-637. McEvoy, P.B. and C. S. Cox. 1987. Wind dispersal distances in dimorphic achenes of ragwort, Senecio jacobaea. Ecology 68(6): 2006-2015. Mitich, L.W. 1995. Intriguing world of weeds - tansy ragwort. Weed Technology 9: 402-404. Sharrow, S.H. and W.D. Mosher. 1980. Sheep as a biological control agent for tansy ragwort. Journal of Range Management 34(4): 440-482. Suter, M., S. Siegrist-Maag, J. Connolly, and A. Lüscher. 2007. Can the occurrence of Senicio jacobaea be influenced by management practice? Weed Research 47: 262-269. del-Val, E. and M.J. Crawley. 2004. Interspecific competition and tolerance to defoliation in four grassland species. Canadian Journal of Botany 82: 871-877. Prepared By: James S. Jacobs, Plant Materials Specialist Montana/Wyoming, USDA NRCS, Bozeman, Montana Sharlene Sing, Research Entomologist – USDA FS Rocky Mountain Research Station, Bozeman, Montana Species Coordinator: James S. Jacobs, Plant Materials Specialist Montana/Wyoming, Bozeman, Montana Citation Jacobs, J. 2009. Plant Guide for tansy ragwort (Senecio jacobaea L). USDA-Natural Resources