Helonias tenax Pursh

Scientific Name: Helonias tenax Pursh

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | HETE11 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herb |

| Native Locations | HETE11 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Name

Basket-grass, bear lily, elk-grass, fire lily, pine lily, western turkey-beard, white grass

Uses

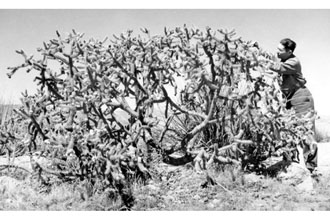

Cultural: Common beargrass leaves were one of the most widely used and highly desirable materials for weaving baskets in northern California, the Pacific Northwest, and the Columbia Plateau and are still gathered today (Bowechop et al. 2012; Hummel et al. 2012; Anderson 2009). Tribes in northern California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana, and First Nations in British Columbia use the leaves for white overlay or decoration on basketry because the leaves are bleached nearly white when dried (Mason 1984:213). Storage baskets, trinket baskets, flour trays, cooking baskets, soup bowls, hats, infant carriers, hoppers, sifters, and dippers all carry its leaves (Figure 2) (Ackerman 1996; Lobb 1984; O’Neale 1995). Beargrass was the decorative material originally selected in making Columbia Plateau style “sally” bags and was later substituted with cornhusk (Figure 3) (Shawley 1975; Schlick 1994). Figure 2. Making a baby rattle with beargrass leaves (white overlay design), woodwardia fern dyed with alder bark (reddish overlay design), and with sandbar willow shoots (weft) and roots (warp). Photograph by Frank K. Lake, 2012. Common beargrass has been gathered in many habitats: Skokomish weavers gathered the leaves in the semi-shade of Douglas-fir savannas after fires in the southeastern Olympic Peninsula in Washington (Peter and Shebitz 2006); Quinault weavers harvested the new, fresh growth in the fire-maintained lowland wetlands of the Olympic Peninsula (Figure 4); the Wasco, Wishxam, and Yakama weavers harvested beargrass in the northeastern Cascades; Maidu women used new leaves from burned over open ponderosa pine forests of the western Sierra Nevada; in the Klamath Mountains, the Takelma, Tolowa, Shasta, Karuk, Hupa, Yurok and Whilkut harvested beargrass from burned sites at mid-to-higher elevation Douglas-fir mixed conifer forests. Figure 3. Mary, Xaawapaanakuy, shown weaving a cornhusk bag at the Astoria, Oregon, Centennial, 1911. Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society (ORHI 57468). Photographer is Wesley Andrews. Common beargrass is thought to be the original decorative material used in making bags and later cornhusk was substituted. Figure 4. Justine James, Quinault, standing in Moses Prairie, a wetland in traditional Quinault territory of the Olympic Peninsula, Washington that was formerly an important traditional gathering site for beargrass. Former Indian burning, kept wetlands like this one productive and biologically diverse. Without this vital disturbance, these wetlands are disappearing all over the Olympic Peninsula. Photograph by Kat Anderson, 2007. Leaves are pulled from the plant, selecting the longest blades (Nordquist and Nordquist 1983). In areas where little or none grew, such as in Makah territory, it was either gathered beyond territorial boundaries or traded for. The Quileute delivered bundles of beargrass to the Makah by canoe (Archibald 1999). Leaves required elaborate processing prior to weaving. The leaves were checked for blemishes, mold, or other defects and the non-useable leaves were discarded. The choice leaves were dried in the shade or sun, sorted into different sizes and some tribes then braided bundles for storage (Figure 5) (Nordquist and Nordquist 1983). Certain tribes, particularly those in the interior Pacific Northwest and the Columbia Plateau dyed beargrass leaves for additional desired colors (Schlick 1994). Prior to use, the central rib was removed from each leaf with a sharp mussel shell knife or other tool, but today a knife is preferred. Other tribes flattened or scraped lightly the central ribs. The fibers were then sized into uniform widths of similar length, and blade taper. Other tribal practitioners sorted clean white from reddish brown-tinged leaves for different purposes. Figure 5. Sundried and naturally bleached out bundles of beargrass to be stored for future Karuk weaving. Photograph by Frank K. Lake, 2012. Courtesy of Kathy McCovey (Karuk). Lela Mae Morganroth, Quileute, from western Washington, (pers. comm. 2005) describes how the leaves were dried and processed: “My grandmother would take an armload. She would separate the long ones from the short ones and then take a handful and braid them around the bundle and then hang it up in the sun or a warm place so that the water comes out and [the leaves] become bleached white. It takes about ten months to a year to get that color. After it’s dried and bleached, you have to scrape the back until it’s like silk. There’s no sharpness on there.” The tawny-colored beargrass contrasts with western redcedar bark, black maidenhair fern stems and red alder-dyed backgrounds and it adds texture to the basket’s surface. A clean white color was obtained by using the bleached leaves of beargrass but the leaves could also be readily dyed other colors (Curtis 1913:62). The Klallam, Klikitat, Snohomish and many other tribes used barberry (also known as oregongrape) (Mahonia nervosa and Mahonia aquilifolium) bark or the root of sand dock (Rumex venosa) to dye beargrass leaves yellow (Colville 1984). A favorite yellow dye for beargrass in northern California is derived from a tree lichen (Evernia vulpina). The black color in Quileute baskets came from burying material in a bed of blue clay or mud for a few weeks (Lela Mae Morganroth, Quileute, pers. comm. 2005). Figure 6. Makah basketmaker at Neah Bay, Makah Reservation, using beargrass and western redcedar bark weaving materials circa 1936. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, Sandpoint, Seattle, WA. Some of the tribes that used beargrass in their basketry include the Achomawi, Atsugewi, Chimariko, Hupa, Karuk, Lassik, Maidu, Nongatl, Shasta, Sinkyone, Tolowa, Wailaki, Whilkut, Wintu, Wiyot, Yana, Yokuts, Yuki, and Yurok of northern California (Merrill 1923); the Chinook, Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, Coquille, and Warmsprings Tribes of Oregon; the Chehalis, Cowlitz, Quileute, Hoh, Klallam, Klikitat, Makah, Quinault, Skokomish, Snohomish, Spokane, and Yakama of Washington (Figure 6) (Gunther 1973; Jones 2012; Ross 1998; Schuster 1998; Wray 2012); the Wasco and Wishram of the Oregon-Washington border (French and French 1998); and the Hesquiat, Lilllooet, Nitinaht, and Okanagan-Colville of Washington and British Columbia (Kennedy and Bouchard 1998; Turner and Efrat 1982; Turner et al 1980; 1983). The Nez Perce along the Snake River in Idaho, the Coeur d’Alene of northern Idaho, and the tribes of Montana such as the Blackfeet, Cree, Crow, Kootenai and Northern Cheyenne also used common beargrass leaves in basketry (Blankenship 1905; Johnston 1987). Ceremonial regalia of many tribes also incorporated beargrass for different decorative or structural elements. Northwestern California and southwestern Oregon Tribes stuffed men’s ceremonial head rolls with beargrass leaves and hair ornaments, necklaces and dance aprons worn during ceremonial dances are adorned with braids or wraps of beargrass (Lake personal observation/use; Moser 1989). Quinault spruce root rain hats had decorative elements of beargrass. Quivers incorporated beargrass as well as the fur of river otter, mink, fisher and pine martens. The Makah kept harpoon points, used in killing whales, in a case made of cedar bark and decorated at one end with beargrass (Olson 1936; Densmore 1939:50). The Shasta and Takelma of southern Oregon made snares from beargrass leaves. These snares were placed in small openings fences and used in conjunction with burning to directionally force and ensnare deer. Figure 7. Demonstrating the typical northwestern California tribal way to harvest beargrass—pulling out individual leaves or the smallest central whorl, taking a few leaves per plant. If cut down to the roots, the wrong manner of harvest, the plant often will not grow back. August 2007, Klamath Mountains,USFS-Orleans Ranger District. Photograph by Frank K. Lake. Powell and Morganroth (1998:22) describe the importance of common beargrass to the Quileutes in western Washington: “The Quileutes considered it to be the most valuable weaving material. Each family had one or more patches that they would exploit and locations would often be kept secret. The grass was picked after June, and then dried by hanging in bundles about three feet four inches wide with the top quarter tied in an overhand knot.” Most tribes with a history of beargrass use continue to use it today. Common beargrass is still harvested by weavers in June, July, or August (Figure 7) (Anderson 2009; Nordquist and Nordquist 1983). They use it in baskets and regalia, as well as in necklaces, earrings, and other pieces of jewelry because it provides a glossy, golden-brown patina. However, development, habitat destruction, and commercial harvesting have severely depleted the resource. Additionally, fire suppression, and tree densification, plantations, have reduced access to harvesting sites. Florists and nurserymen also admire the sleek, delicate lines of common beargrass and thus the leaves have become a popular part of prepackaged bouquets and customized floral arrangements. Commercial harvesters compete with native gatherers, cutting thousands of pounds of the plant to sell for floral arrangements in the United States, Europe, and Asia (Hummel et al. 2012). Wildlife: Deer, elk, bighorn sheep, and Rocky Mountain goats feed on common beargrass flower stalks and/or leaves and dense mats of beargrass provide feeding habitat for pocket gophers and other small mammals (Young and Robinette 1939; Wick et al. 2008; Hemstrom et al. 1982; Crane 1990). Black bears eat the softer leaf-bases in early spring and grizzly bears use beargrass leaves as a nesting material in their winter dens (Clark 1998; Almack 1986). Beargrass flowers are pollinated by various species of flies, beetles, and bees (Vance et al. 2004). In one study, 138 insect foragers from these three insect orders were observed upon beargrass flowers (Hummel et al. 2012).

Status

Development, habitat destruction, commercial harvesting and absence of traditional land management have depleted some common beargrass colonies. Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Description

General: A member of the Melanthiaceae, but sometimes classified in the Liliaceae, common beargrass is an herbaceous perennial with flowering stalks up to 1.8 m tall. It has hundreds of small, fragrant, creamy white flowers on terminal racemes and has a thick woody rootstock with short rhizomes. The flowers bloom from spring to early summer. The numerous, linear leaves are grass-like, evergreen, tough, and up to 90 cm long. The finely toothed edges of the leaves can cut unprotected hands (Piper and Beattie 1915:102; Hitchcock and Cronquist 1973:696; Pojar and MacKinnon 1994:112). Distribution: The plant is found as far north as British Columbia and south to California and east into Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. It occurs from sea level on the Olympic Peninsula to 2300 m elevation in the Rocky Mountains (Utech 2002). Figure 8. Karuk basketweaver LaVerne Glaze gathering beargrass, USFS Orleans Ranger District in July 2005, with the Passport in Time-Follow the Smoke project. Photograph by Frank K. Lake. Habitat: It is moderately shade tolerant and it appears in clumps in clearings, prairies, bogs, ridge tops, rocky slopes and open woods from sea level to 2300 m (Utech 2002). It grows in association with many kinds of conifers including Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), grand fir (Abies grandis), Pacific silver fir (Abies amabilis), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), western white pine (Pinus monticola) and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta). It can be found in all soil types, but prefers xeric to subxeric and submesic sites (Wick et al. 2008).

Adaptation

Studies show saw palmetto not only thrives in a fire-prone environment, but is also activated reproductively by fire. Saw palmetto has waxy, evergreen leaves that are quite flammable. After fire, the plant resprouts from root crowns and rhizomes and grows rapidly (Abrahamson 1984; 1999; Van Deelen 1991; Schmalzer and Hinkle 1992). Winter-burned stands recover faster than summer-burned stands (Abrahamson 1984). However, seedlings grow slowly, especially on nutrient-poor soils, and they have a limited ability to recolonize former habitats (Abrahamson 1995). Figure 9. USDA Forest Service, Six Rivers National Forest, Orleans Ranger District, prescribed cultural burn in the mixed conifer forest of the western Klamath Mountains to enhance beargrass for tribal basketweavers. October 2005. Photograph by Frank K. Lake.

Establishment

Beargrass can be propagated by seeds, Collect the light tan seeds in late August to early September when the capsules turn tan and open, Beargrass seeds need 14 weeks of cold stratification prior to planting and sixteen weeks if gathered at high elevations (Shebitz et al, 2009a; Smart and Minore 1977), Seeds germinate best in vermiculite (Crane 1990), In a greenhouse experiment, Shebitz et al, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Helonias tenax Pursh., (2009a) found that beargrass seed germination rates significantly increased when the seeds were exposed to smoke-water prior to undergoing cold stratification, If sowing the seeds outdoors, clear all debris and expose the bare mineral soil before planting (Shebitz et al, 2009a), Offshoots of beargrass collected from the wild do not readily establish in containers, For more detailed methods of propagation, see Wick et al, (2008),

Management

Common beargrass is tended by the use of harvest methods that ensured the survival of individual plants. Rosie Black (Quileute) told Muriel Huggins that “You're supposed to pull the beargrass leaves, never cut them. And do not pull up the ones with the blossoms. By pulling one at a time you’re going to have more in the next years. You’ve got to preserve it.” By harvesting the leaves in this way, Indians stimulated new growth and maintained plant vitality (Figure 8). Bea Charles (Klallam, pers. comm. 2006) noted: “You never over-take anything from any of the plants and trees. We want them to live and have a long life. You’ve got a certain beargrass that you leave in the ground because that replenishes. That keeps replenishing that bush. And there are [only] certain straws that you pull out…it makes room [for the plant] to make more [leaves].” Untended clumps can become very messy and clogged with dead leaves. Regular harvest prevents or reduces this accumulation of dead material. Many active basketweavers claim that it is good for the plants to remove the young shoots almost every year so that they can’t cause congestion. Ethnobotanists Nancy Turner and Sandra Peacock made the following observation about the Nuu-chah-nulth on Vancouver Island: “Plants like basket sedge [Carex obnupta], bear-grass (Xerophyllum tenax), cattail, [Typha latifolia] tule (Schoenoplectus acutus), and stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), sought for their leaves or stems as weaving and cordage materials, were cut in the late summer when the plants were at full maturity. Since these plants are perennials and their root systems were not impacted in harvesting, they would continue to grow the following year, and some people say they are even more prolific with cutting or pruning” (Turner and Peacock 2005:122). Some harvesters for the floral trade cut whole plants to the roots and as a result, the beargrass doesn’t grow back (Anderson 2005; 2009). The demand for common beargass, however, has motivated at least one tribe to grow it for traditional uses and the commercial market. According to Powell and Morganroth (1998:22): “Since 1996, the Skokomish tribe has cultivated long gardens of beargrass under electric transmission wires that cross their traditional lands and have successfully assured tribal weavers of a supply of grass and an income from selling the flowers and grass.” Burning: Beargrass cannot thrive in full shade. While it thrives in full sunlight, the best quality beargrass leaves grow in light shade under an open canopy (Vance et al. 2001; Shebitz 2006).There is evidence that common beargrass was burned in the forests of northern California and western Washington, to enhance the material for basketry, as well as to improve the habitat (Anderson 2005; 2009; Peter and Shebitz 2006; Shebitz 2006; Shebitz et al. 2009b). The Yurok, Karuk, Hupa, Chilula, and other tribes in northern California burned beargrass clumps in the mixed evergreen forests in the outer Coast Ranges and western Klamath-Siskiyou mountains of northern California periodically from July to early fall, before the rains began and the new green leaves that sprout after a burn are more easily picked and worked, as they are stronger, thinner, and more pliable (Goddard 1903-4; Gibbs 1853; Harrington 1932; Kroeber 1939; O’Neale 1995; Rentz 2003). In the late 1920s Lila O’Neale (1995) spent time among Karuk and Yurok basketweavers in northern California and recorded that “older weavers of the idyllic days knew just where to set their annual fires and a fine growth of long-strand grass would result.” A recent publication of the Coquille in Oregon, Ethnobotany of the Coquille Indians (Fluharty et al. 2010:19) instructs the reader that beargrass “patches need to be burned every three years in early fall when vegetation is dry for harvesting the following spring.” Figure 10. U.S. Forest Service Fire Crew conducting a cultural burn on September 30, 2003 in Olympic National Forest with the goal of restoring historic beargrass savannas important to the Skokomish. Photograph by Daniela Shebitz. Ecotones at the margins of prairies and wetlands in western Washington were often ideal locations, generating excellent basketry material for weavers, but the ecotones had to be periodically burned to maintain their semi-open, partly shaded character. Chet Pulsipher, a Skokomish elder, informed Justine James, Quinault, and (pers. comm. 2005) that “there was burning in the Moses Prairie for beargrass.” Beatrice Black, a Quileute basketweaver, also confirmed burning on Moses Prairie in interviews with James. According to James (pers. comm. 2005), Black gathered beargrass leaves on Moses Prairie in July and her family burned it right before they left, in late July or August. Daniela Shebitz learned from Bruce Miller, a Skokomish elder and master basketmaker, that the Skokomish formerly burned the prairies with care of the beargrass resource in mind. “The Skokomish maintained a network of prairies and rotated the burning so that each burned every two to three years,” relates Shebitz. “Burning was conducted in autumn and varied in size from a few meters to hectares. He [Miller] described that beargrass occurred in the savanna-like border between prairie and forests” (Shebitz 2005:62). Through Skokomish oral tradition, historical documents, tree-ring analysis and other evidence, ecologists David Peter and Daniela Shebitz (2006) have uncovered a former indigenous fire-maintained landscape in the Southeastern Olympic Peninsula of widely spaced Douglas-fir trees with an understory of common beargrass. With the ceasing of indigenous burning in the 1800s, forests have grown up in the openings, requiring prescribed burning to restore this anthropogenic ecosystem (Peter and Shebitz 2006). Figure 11. Beargrass cultural burn, conducted by USFS Fire Crew on the Happy Camp Ranger District, Klamath National Forest, 2010. Photo by Todd Drake. By burning to foster the plants and habitat and gathering the leaves judiciously, Native Americans were practicing conservation. Scientists have documented that beargrass flowering is enhanced in forest openings created by disturbances such as fire, and flowering becomes less frequent or non-existent as the forest canopy recloses. By maintaining these open habitats, Indians were therefore, benefiting the over 100 species of native flies, bees, and beetles that pollinate beargrass flowers. Hummel et al. (2012) concluded that: “Given the length of time Native Americans have been burning in some beargrass regions and habitats, the extent and frequency of burns, and the genetic response of plants to such disturbance, this species may belong to an anthropogenic fire-dependent ecosystem inherently unstable now that management practices have changed.” Beargrass savannas on the Southeastern Olympic Peninsula may qualify as such human-made ecosystems, because in the absence of Indian-set fires they lose their character, shifting to more densely forested vegetation (Peter and Shebitz 2006). Figure 12. Quinault Indian Nation Fire Crew burning an ecotone to restore beargrass plants and habitat, September 2004. Photograph by Daniela Shebitz. a number of national forests, including Klamath, Six Rivers and Plumas National Forests in California, Willamette National Forest in Oregon, and Olympic National Forest in Washington, partner with tribes to conduct cultural burnings to restore and enhance common beargrass populations and maintain open habitat (Figures 9, 10 and 11) (Hunter 1988; Lee 2000; Parker 2007; Shebitz 2005). Furthermore, tribes are directly bringing back the traditional ways of their ancestors, by conducting burns for culturally significant plants on their reservations (Figure 12). Given that indigenous people have maintained a variety of ecosystems where beargrass thrives with fire, it behooves restoration practitioners to consider both natural and anthropogenic disturbance in their conservation strategies (Charnley and Hummel 2011). The staffs of various national forests are now recognizing that traditional and local ecological knowledge can make significant contributions to the conservation of ecosystem diversity (Charnley and Hummel 2011; Hummel et al. 2012). Cultivars, I Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Seeds of common beargrass are widely available from native plant nurseries.

References

Ackerman, L.A. (ed.). 1996. A Song to the Creator: Traditional Arts of Native American Women of the Plateau. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Almack, J. 1986. Grizzly bear habitat use, food habits, and movements in the Selkirk Mountains, northern Idaho. Pages 150-157 in: Grizzly Bear Habitat Symposium April 30, 1985 Proceedings. G.P. Contreras and K.E. Evans, compilers. Missoula, MT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-207. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. Anderson, M.K. 2005. Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California's Natural Resources. University of California, Berkeley. ______________. 2009. The Ozette Prairies of Olympic National Park: Their Former Indigenous Uses and Management. Final Report to Olympic National Park, Port Angeles, WA. Archibald, L. 1999. There was a Day: Stories of the Pioneers. Printed by Olympic Graphic Arts, Inc., Forks, WA. Blankenship, J.W. 1905. Native Economic Plants of Montana. Montana Agricultural College Experimental Station Bulletin 56, Bozeman. Bowechop, J., V. Charles-Trudeau, D. Croes, C. Kalama, C. Morganroth III, T. Parker, V. Riebe, L. Shale, and J. Wray. 2012. Pages 170-177 in: From the Hands of a Weaver: Olympic Peninsula Basketry Through Time. J. Wray (ed.). University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Bradley, A.F. 1984. Rhizome morphology, soil distribution, and the potential fire survival of eight woody understory species in western Montana. Thesis. University of Montana, Missoula. Charnley, S. and S. Hummel. 2011. People, Plants, and Pollinators: The Conservation of Beargrass Ecosystem Diversity in the Western United States. Clark, L. 1998. Wild Flowers of the Pacific Northwest. J.G. Trelawny (ed.). Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park, BC Canada. Cooke, S.S. 1997. A Field Guide to the Common Wetland Plants of Western Washington and Northwestern Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle. Colville 1984. Plants used in basketry. Pages 199-214 In: Aboriginal American Indian Basketry: Studies in a Textile Art without Machinery. Otis Tufton Mason, author. Reprint of the Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, June 30, 1902. Report of the U.S. National Museum. The Rio Grande Press, Inc. Glorieta, New Mexico. Crane, M.F. 1990. Xerophyllum tenax. In:

Fire Effects

Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2011, February 18]. Curtis, E.S. 1913. The North American Indian: The Indians of the United States, the Dominion of Canada, and Alaska. Volume 9. Reprinted by Johnson Reprint Corporation, New York, N.Y. Densmore, F. 1939. Nootka and Quileute music. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 124. United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. Fluharty, S., D. Hockema, and N. Norris. 2010. Ethnobotany of the Coquille Indians: 100 Common Cultural Plants. Coquille Indian Tribe, Cultural Resources Program. French, D.H. and K.S. French. 1998. Wasco, Wshram, and Cascades. Pages 360-377 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 12: Plateau. D.E. Walker, Jr. Volume Editor. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gibbs, G., 1853. Journal of the expedition of Colonel Redick McKee, United States Indian agent, through North-Western California. Pages 99-177 in: Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Conditions and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Vol. 3: Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. H.R. Schoolcraft (ed.). Lippincott, Grambo, Philadelphia. Goddard, P.E. 1903-4. Life and culture of the Hupa. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 1(1):1-88. Gunther, E. 1973. Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native Americans. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Harrington, J.P. 1932. Tobacco among the Karuk Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 94. Washingtion, D.C. Hemstrom, M.A., W.H. Emmingham, N.M. Halverson, and others. 1982. Plant association and management guide for the Pacific silver fir zone, Mt. Hood and Williamette National Forests. R6-Ecol 100-1982a. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region. Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 1973. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Hummel, S., S. Foltz Jordan, and S. Polasky. 2012. Natural and Cultural History of Beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax). USDA Forest Service, PNW Research Station

General

Technical Report (PNW-GTR-864), Portland, OR. Hunter, J.E. 1988. Prescribed Burning for Cultural Resources. Fire Management Notes 49(2)8-9. Johnston, A. 1987. Plants and the Blackfoot. Lethbridge Historical Society, Lethbridge, Alberta. Jones, J.M. 2012. Quinault basketry. Pages 78-91 in: From the Hands of a Weaver: Olympic Peninsula Basketry Through Time. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Kennedy, D. and R.T. Bouchard. 1998. Lillooet. Pages 174-190 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 12: Plateau. D.E. Walker, Jr. Volume Editor. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Kroeber, A.L. 1939. Unpublished field notes of the Yurok. University Archives, Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley. Kruckeberg, A. 2003. Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press, Seattle. Lee, J.T. 2000. Emphasis on the regeneration of the bear grass (Xerophyllum tenax) within the Wolf Timber sale. Technical Fire Management Proposal TFM-14. USDA Forest Service Region 5 Plumas National Forest Mount Hough Ranger District. Lobb, A. 1984. Indian Baskets of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. Graphic Arts Center Publishing Co. Portland, OR. Mason, O.T. 1984. Aboriginal American Indian Basketry. The Rio Grande Press, Inc. Glorieta, New Mexico. Previously published in 1902 under the title Aboriginal Indian Basketry as part of the Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, Report of the U.S. National Museum. Merrill, R.E. 1923. Plants used in basketry by the California Indians. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 20(13):215-42. Moser, C.L. 1989. American Indian Basketry of Northern California. Riverside Museum Press, Riverside, CA. Nordquist, D.L. and G.E. Nordquist. 1983. Twana Twined Basketry. Acoma Books, Ramona, CA. Olson, R.L. 1936. The Quinault Indians. University of Washington Press, Seattle. O’Neale, L.M. 1995. Yurok-Karok Basket Weavers. Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley. Parker, V. 2007. Bear grass burn planned for Plumas National Forest. Resource Policy Report. Roots and Shoots. Newsletter 49:6 of the California Indian Basketweavers Association. Peter, D. and D.J. Shebitz. 2006. Historic anthropogenically-maintained beargrass savannas of the southeastern Olympic Peninsula. Restoration Ecology 14(4):605-615. Piper, C.V. and R.K. Beattie. 1915. Flora of the Northwest Coast. Press of the New Era Printing Co. Lancaster, PA. Pojar, J. and A. MacKinnon, (eds.). 1994. Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska. Vancouver, B.C.: Ministry of Forests and Lone Pine Publishing. Powell, J. and C. Morganroth III. 1998. Quileute Use of Trees & Plants: A Quileute Ethnobotany. Prepared for Quileute Natural Resources, LaPush, Washington. Rentz, E. 2003. Effects of Fire on Plant Anatomical Structure in Native Californian Basketry Materials. MS Thesis, San Francisco State University. Ross, J.A. 1998. Spokane. Pages 271-282 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 12: Plateau. D.E. Walker, Jr. Volume Editor. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Schlick, M.D. 1994. Columbia River Basketry, Gift of the Ancestors, Gift of the Earth. University of Washington Press, Seattle. Schuster, H.H. 1998. Yakima and neighboring groups. Pages 327-351 in: Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 12: Plateau. D.E. Walker, Jr. Volume Editor. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Shawley, S.D. 1975. Hemp and cornhusk bags of the Plateau Indians. Indian America 9(1):25-29, 48-49. Shebitz, D.J. 2005. Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into the restoration of basketry plants. Journal of Ecological Anthropology 9:51-68. ___________. 2006. The Historical Role and Current Restoration Applications of Fire in Maintaining Beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax (Pursh) Nutt.) Habitat on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington State. Ph.D. Dissertation College of Forest Resources. Shebitz, D.J., K. Ewing, and J. Gutierrez. 2009a. Preliminary observations of using smoke-water to increase low elevation beargrass Xerophyllum tenax germination. Native Plants Journal 10(1):13-20. Shebitz, D.J, S.H. Reichard, and P.W. Dunwiddie. 2009b. Ecological and cultural significance of burning beargrass habitat on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington. Ecological Restoration 27(3):306-319. Smart, A.W., and D. Minore. 1977. Germination of beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax [Pursh] Nutt.). The Plant Propagator 23(3):13-15. Turner, N.J. and B.S. Efrat 1982. Ethnobotany of the Hesquiat Indians of Vancouver Island. British Columbia Provincial Museum, Victoria. Turner, N.J. and S. Peacock. 2005. Solving the perennial paradox: ethnobotanical evidence for plant resource management on the Northwest Coast. Pages 101-150 in: Keeping It Living: Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. D. Deur and N.J. Turner (eds.). University of Washington Press, Seattle. Turner, N.J., R. Bouchard, and D.I.D. Kennedy. 1980. Ethnobotany of the Okanagan-Colville Indians of British Columbia and Washington. British Columbia Provincial Museum, Victoria. Turner, N.J., J. Thomas, B.F. Carlson, and R.T. Ogilvie. 1983. Ethnobotany of the Nitinaht Indians of Vancouver Island. British Columbia Provincial Museum, Victoria. Utech, F.H. 2002. Xerophyllum. Pages 71-72 in: Flora of North America North of Mexico Vol. 26. Magnoliophyta: Liliidae: Liliales and Orchidales. Flora of North America Editorial Committee (eds.). Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y. Vance, N.C., M. Borsting, D. Pilz, and J. Freed. 2001. Special Forest Products: Species Information Guide for the Pacific Northwest. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. Portland, OR. Vance, N.C., P. Bernhardt, and R.M. Edens. 2004. Pollination and seed production in Xerophyllum tenax (Melanthiaceae) in the Cascade Range of Central Oregon. American Journal of Botany 91(12):2060-2068. Wick, D., J. Evans, and T. Luna. 2008.

Propagation

protocol for production of container Xerophyllum tenax (Pursh) Nutt. Plants (160 ml containers); USDI NPS—Glacier National Park, West Glacier, Montana. In: Native Plant Network. URL: http://www.nativeplantnetwork.org. Moscow (ID): University of Idaho, College of Natural Resources, Forest Research Nursery. Wray, J. (ed.). 2012. From the Hands of a Weaver: Olympic Peninsula Basketry Through Time. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Young, V.A. and W.L. Robinette. 1939. A Study of the Range Habits of Elk on the Selway Game Preserve. Bull. No. 9. University of Idaho, School of Forestry. Moscow, ID. Prepared By: M. Kat Anderson, USDA NRCS National Plants Team, Frank K. Lake, fire ecologist with Pacific Southwest Research Station, and Tim Oakes, USDA NRCS Liaison-Conservation Program Analyst to the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Citation Anderson, M.K., F.K. Lake, and T. Oakes 2015. Plant Guide for common beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Plants Team. Davis, CA 95616. For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | 7 |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | No |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | None |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | Low |

| Cold Stratification Required | Yes |

| Drought Tolerance | Medium |

| Fertility Requirement | Low |

| Fire Tolerance | High |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 120 |

| Hedge Tolerance | High |

| Moisture Use | Low |

| pH, Maximum | 7.2 |

| pH, Minimum | 5.5 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 69 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 19 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 6 |

| Salinity Tolerance | None |

| Shade Tolerance | Intermediate |

Morphology/Physiology

| After Harvest Regrowth Rate | Rapid |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | None |

| Shape and Orientation | Erect |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Resprout Ability | No |

| Active Growth Period | Spring and Summer |

| Bloat | None |

| C:N Ratio | High |

| Coppice Potential | No |

| Fall Conspicuous | No |

| Fire Resistant | No |

| Flower Color | White |

| Flower Conspicuous | Yes |

| Foliage Color | Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Porous |

| Foliage Texture | Fine |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Lifespan | Short |

| Leaf Retention | No |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Height, Mature (feet) | 5.0 |

| Growth Rate | Rapid |

| Growth Form | Rhizomatous |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | No |

| Fruit/Seed Color | Black |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Porous |

Reproduction

| Vegetative Spread Rate | Slow |

|---|---|

| Small Grain | No |

| Seedling Vigor | Low |

| Seed Spread Rate | Slow |

| Seed per Pound | 217333 |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | No |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | No |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Seed | Yes |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

| Propagated by Container | No |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | No |

| Fruit/Seed Period End | Fall |

| Fruit/Seed Period Begin | Summer |

| Fruit/Seed Abundance | Low |

| Commercial Availability | Field Collections Only |

| Bloom Period | Summer |

| Propagated by Cuttings | No |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | No |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | No |

| Protein Potential | Low |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | No |

| Palatable Graze Animal | Low |

| Palatable Browse Animal | Low |

| Nursery Stock Product | No |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | No |

| Fodder Product | No |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | No |