Glechoma hederacea L. var. parviflora (Benth.) House

Scientific Name: Glechoma hederacea L. var. parviflora (Benth.) House

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | GLHEP |

| Group | Dicot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herb |

| Native Locations | GLHEP |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Alternate Common Names: creeping Charlie creeping Jenny gill over the ground field balm haymaids cat’s foot alehoffs Alternate Scientific Names: Glecoma hederacea L. Glechoma hederacea L. var. micrantha Moric. Glechoma hederacea L. var. parviflora (Benth.) House Nepeta hederacea (L.) Trevis.

Uses

Ethnobotanical: Ground ivy was used as a flavoring and clearing agent in brewing beer before it was replaced by hops (Mitich, 1994). Germans began using hops in the 8th century, but hops were not introduced to England until the14th century (Hatfield, 1971). Many people believed hops were dangerous to their health until the 17th century (Hatfield, 1971). One of ground ivy’s common names, alehoffs, means “ale ivy”. It is derived from the old English brewing term, hofe (Durant, 1976). Another of ground ivy’s common names contains the word gill, which is from the French word guiller, meaning “to ferment ale” (Hatfield 1971). Ground ivy was also used for treating innumerable medical conditions. Graeco-Roman mythology claimed it cured melancholy (Hatfield, 1971). European herbalists used it to treat disorders of the bladder, kidneys, digestive tract and skin; gout, coughs, colds, and ringing in the ears (Gerard, 1964). They also used it to cure eye disorders in livestock (Gerard, 1964). Early English settlers brought ground ivy to the New World as part of their standard stock of household herbs (Hatfield, 1971). During the 19th century in the U.S., ground ivy was used for treating lung and kidney diseases, asthma, jaundice, hypochondria, “monomania” (a condition of “partial insanity”), and it was snuffed to treat persistent headache (Lestrange, 1971 as cited by Mitich, 1994). Ground ivy was also given to painters to treat “lead-colic” (Durant, 1976). The plant is still used in herbal medicine in modern times, for its astringent, diuretic and stimulant properties (Hatfield, 1971; Waggy, 2009). Old English recipes recommended adding ground ivy to jams, soups, oatmeal and vegetable dishes (LeStrange, 1977, as cited by Mitich, 1994). Wreathes were once made with the trailing stems of ground ivy and placed on the dead, and the Swiss believed when worn with rue, agrimony, maiden-hair and broom straw, it could improve vision and indicate the presence of witches (Blatchley, 1930). Ground ivy is high in iron and is a valuable addition to compost (Hatfield, 1971). Ornamental: Ground ivy is sold by garden nurseries for a ground cover and hanging baskets. The variegated cultivar ‘Variegata’ is tremendously popular. In Europe, the variegated cultivar has been found growing in natural habitats (Hutchings and Price, 1999). Wildlife: Many species of invertebrates and a few species of mammals utilize ground ivy for forage in Europe (Watts, 1968; Hutchings and Price, 1999). In the U.S., it is a potential food source for introduced boars in the Smokey Mountains (Bratton, 1974). Livestock: Ground ivy is toxic to horses if they consume a large amount of fresh material or hay (Kingsbury, 1964; Vanselow and Brendieck-Worm, 2012). Vanselow and Bredick-Worm (2012) concluded from a literature review horses may experience toxicosis if they consume alfalfa hay containing 30% or more ground ivy or if they feed exclusively on ground ivy. The toxicity may be caused by the volatile oils common in many Lamiaceae species (Kingsbury, 1964). Symptoms of toxicity include sweating, salivation, labored breathing, pupil dilation and occasionally signs of pulmonary edema (Kingsbury, 1964). No other forms of livestock are known to be affected. Livestock in general tend to avoid ground ivy because of its bitter taste.

Status

Glechoma hederacea is native to Europe and Asia, and was brought to the U.S. by early European colonists (Mack, 2003). It is listed as a noxious species in Connecticut (USDA NRCS, 2013). In most states, it is listed as a facultative upland species. It usually occurs in non-wetland habitats but has 1 to 33% probability of occurring in a wetland (USDA NRCS, 2013).

Weediness

Ground ivy may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats (USDA NRCS, 2013). Plants are clonal and form dense mats. They rapidly colonize a disturbed site by producing stolons and ramets (overwintering stolon fragments). The plants can morphologically adapt to changes in environmental conditions such as nutrient and light availability (Slade and Hutchings, 1987). They produce more vertical and horizontal growth in the presence of other plants to avoid competition (Hutchings and Price, 1999). Plants reproduce primarily by vegetative means, with rosettes and ramets (Waggy, 2009). They also reproduce by seed. Four seeds are produced per flower, and the seeds are dispersed by gravity and animal transport (Bouman and Meeuse, 1992). The viability of seed may vary from less than one year to multiple years, depending on environmental conditions (Waggy, 2009). There is little information regarding the impact of ground ivy on native plant communities, which may suggest it is less of a threat than other invasive species (Waggy, 2009). The turf grass industry, however, considers ground ivy a significant threat to lawns. It disrupts turf uniformity and is very difficult to eradicate (Hatterman-Valenti et al., 1996; Spangenberg, 2001; Kohler et al., 2004). Consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding this plant’s status and use. Consult the Related Web Sites on the Plant Profile for this species for further information. Glechoma hederacea flowers. Ben Legler, University of Washington Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture

Description

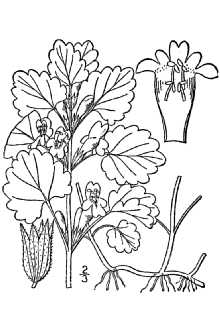

General: Mint family (Lamiaceae). Glechoma hederacea is perennial forb introduced from Europe. It is clonal and forms carpet-like mats, with long, slender, square stolons that produce fibrous roots at the nodes. Rosette buds also form at the stolon nodes, which develop into secondary stolons and ramets (overwintering stolon fragments). Plant growth is primarily horizontal, except during flowering, when stolon tips grow upwards. Upright stems can reach a height of 4 to 16 inches tall. After flowering, the stems arch down and resume horizontal growth. The vertical stems are thicker than the stolons, are smooth or covered with short, stiff hairs, and have long, soft, straight hairs at the nodes. Leaves are opposite, have petioles, and are 0.4 to 1.2 inches long. Leaves are smooth or have stiff hairs, are heart- or kidney-shaped and have rounded teeth. Flowers occur in verticils that originate in the leaf axils. They have short pedicels and calyxes with 15 nerves and long upper teeth. Flowers bloom early to mid or late season, depending on geographic region, and are blue-violet with purple spots. They have a tubular shape, 0.5 to 0.9 inch long, with unequal lobes. The central lobe is spreading and much larger than the lateral and upper lobes. Flowers have 4 stamens, with the upper pair longer, and the style is slender, divided into two parts. The ovaries are two-celled and superior. The fruit has four nutlets, each containing one seed. Plants reproduce sexually by seed, and vegetatively by rosettes and ramets. In warmer climates, the plants may be evergreen. (Hitchcock and Cronquist, 1973; Slade and Hutchings, 1987; Hutchings and Price, 1999; Waggy, 2009; Burke Museum of Natural History and Cutlure, 2013). The genus name Glechoma is from an old Greek name for mint or thyme, glechon; and the species name hederacea means “of or pertaining to ivy” in Latin (Charters, 2013). Distribution: The first report of ground ivy in North America was in 1672 in New England (Wells and Brown, 2000 as cited by Waggy, 2009). It is now found in all of the United States except New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and Hawaii, and all Canadian provinces (USDA NRCS, 2013). It has not spread to the Canadian territories Nunavut, Northwest Territories and the Yukon. For current distribution, consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Glechoma hederacea grows in riparian areas, deciduous forests, thickets, wetlands and prairies (Waggy, 2009; Voss and Reznicek, 2012). It is often found in disturbed areas such as roadsides, fallow fields, and pasture edges (Bryson and DeFelice, 2010; Voss and Reznicek, 2012). It also invades lawns and gardens. Glechoma hederacea leaf. Ben Legler, University of Washington Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture

Adaptation

This plant will grow in many soil types, including riparian, floodplain and wetland soils that are moist but not saturated, and in heavily compacted soils (Waggy, 2009). In Europe, it grows at elevations from sea level to 5,200 feet (Hutchings and Price, 1999). In the U.S., it has been documented at elevations of 1,900 to 6,000 feet (Waggy, 2009). The plant primarily grows in shaded environments but will also grow in full sunlight, particularly where the ground has been disturbed (Bryson and DeFelice, 2010).

Pests and Potential Problems

None known in North America.

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

Ground ivy may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats (USDA NRCS, 2013). It is toxic to horses when consumed in large quantities (Kingsbury, 1964).

Control

Ground ivy is difficult to control with mechanical methods because the plant produces rooting stolon fragments (Kohler et al., 2004). Physical control, by hand-pulling or raking the plants, is possible only if all stolon fragments are removed. Ground ivy is also difficult to control with chemical methods because plants will reestablish soon after post-emergence treatment (Spangenberg, 2001; Kohler et al., 2004). To control ground ivy in lawns, Spangenberg (2001) recommends a three-way broadleaf herbicide mixture of 2,4-D, mecoprop (MCPP) and dicamba. Mixtures with clopyralid, dichlorprop, triclopyr, and MCPA may also be effective. The herbicide mixture should be applied mid-spring to early summer and mid-to late fall, when the plant is in bloom or at the time of the first frost, and the plants should not be mown a few days before and after herbicide application (Spangenberg, 2001). Kohler et al. (2004) compared the effectiveness of triclopyr, clopyralid, MCPP, 2,4-D amine, 2,4-D ester, dicamba, quinclorac, and fluroxypyr alone or in mixtures, applied at different times and rates to control ground ivy. They found mixtures containing 2,4-D amine, 2,4-D ester, fluroxypyr, or triclopyr applied in the fall at the highest labeled rates were the most effective. They also tested various pre-emergent herbicides, and found isoxaben prevented the growth and development of ground ivy stolons. Other pre-emergent herbicides: prodiamine, pendimethalin and dithiopyr had no effect. A combination of cultural and chemical methods is needed to eradicate ground ivy from lawns (Spangenberg, 2001; Kohler et al., 2004). Cultural methods for prohibiting the spread of ground ivy include (Spangenberg 2001): • planting shade-tolerant grass, such as fine-leaf fescues (Festuca spp.), rough bluegrass (Poa trivalis), and supine bluegrass (Poa supina) • minimizing stress, since grasses grown in shade do not recover well • improving light conditions and air circulation by trimming trees and shrubs • improving soil conditions by aerating the soil to reduce compaction and improve drainage • mowing at 3” height to increase grass leaf surface area • watering infrequently, but deeply when you do water • fertilizing less (44 to 87 lb nitrogen per acre per year) Kohler et al. (2004) found a higher rate of nitrogen was needed to reduce ground ivy cover, but they conducted experiments on Kentucky bluegrass. They found 174 lb nitrogen per acre per year reduced ground ivy cover by 24%. Kolher et al. (2004) recommends a strategy of applying at least 174 lb nitrogen per acre per year, applying the pre-emergent herbicide isoxaben with or after a post-emergence herbicide, and a fall post-emergence herbicide application containing 2,4-D, fluroxypyr or triclopyr at the highest labeled rate to control ground ivy in lawns. Contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what herbicides work best in your area and how to use them safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) This plant is sold by garden nurseries for a ground cover or hanging baskets. The variegated cultivar, ‘Variegata’, is very popular.

References

Blatchley, W.S. 1930. The Indiana Weed Book, 3rd ed. The Nature Publishing Co., Indianapolis. Bouman, F. and A.D.J. Meeuse. 1992. Dispersal in Labiatae. In: Advances in Labiate Science (R.M. Harley and T. Reynolds, eds.) pp. 193-202. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK. Bratton, S.P. 1974. The effect of the European wild boar (Sus scrofa) in the high-elevation vernal flora in Great Smoky Mountain National Park. Bull. of the Torrey Botanical Club. 101(4):198-206. Bryson, C.T. and M.S. DeFelice. 2010. Weeds of the Midwestern United States and Central Canada. University of Georgia Press, Athens. Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. 2013. Available at http://biology.burke.washington.edu/herbarium/imagecollection.php (accessed 15 Mar 2013). University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Charters, M.L. 2013. California Plant Names: Latin and Greek Meanings and Derivations. Available at http://www.calflora.net/botanicalnames/ (accessed 27 Mar 2013) Michael L. Charters, Sierra Madre, CA. Durant, M. 1976. Who Named the Daisy? Who named the Rose? Dodd, Mead and Co., New York. Gerard, J. 1964. Gerard’s Herball: the essesence thereof distilled by Marcus Woodward (1927) from the edition of T.H. Johnson (1636). Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. Hatfield, A.W. 1971. How to Enjoy your Weeds. Sterling Publishing Co., New York. Hatterman-Valenti, H., M.D.K. Owen, and N.E. Christians. 1996. Ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea L.) control in a Kentucky bluegrass turfgrass with borax. J. Environ. Hort. 14(2):101-104. Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 1973. Flora of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press, Seattle and London. Hutchings, M.J. and E.A.C. Price. 1999. Biological Flora of the British Isles. Glechoma hederacea L. (Nepeta glechoma Benth., N. hederacea (L.) Trev.). J. of Ecol. 87:347-364. Kingsbury, J.M. 1964. Poisonous Plants of the United States and Canada. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Kohler, E.A., C.S. Throssell, and Z.J. Reicher. 2004. Cultural and chemical control of ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea). HortSci. 39(5):1148-1152. Mack, R.N. 2003. Plant naturalizations and invasions in the eastern United States: 1634-1860. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 90:77-90. Mitich, L.W. 1994. The intriguing world of weeds. Ground ivy. Weed Technology. 8(2):413-415. Slade, A.J., and M.J. Hutchings. 1987. The effects of nutrient availability on foraging in the clonal herb Glechoma hederacea. J. of Ecol. 75:95-112. Spangenberg, B. 2001. Lurking in the shadows. Grounds Maintenance. 36(1):36-39. USDA NRCS. 2012. The PLANTS Database, Available at http://plants.usda.gov (Accessed 15 March 2013). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC. Vanselow, R. and C. Brendieck-Worm. 2012. Ground ivy (Glecoma hederacea) and the cause of toxicosis in horses: In search of evidence. Zeitschrift für ganzheitliche Tiermedizin. 26:88-93 Voss, E.G.and A. Reznicek. 2012. Field Manual of Michigan Flora. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. Waggy, M.A. 2009. Glechoma hederacea. In:

Fire Effects

Information System, Available at http://www,fs,fed,us/database/feis/plants/forb/glehed/all,html (Accessed 15 March 2013), U,S, Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT, Watts, C,H, 1968, The foods eaten by wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) and bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) in Wythan Woods, Berkshire, J, of Animal Ecol, 37(1):25-41, Prepared By: Pamela L,S, Pavek, USDA NRCS Plant Materials Center, Pullman, Washington Citation Pavek, P,L, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Glechoma hederacea L. var. parviflora (Benth.) House.,S, 2013, Plant guide for ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea L,) USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Pullman, WA, Published May 2013 Edited: 22April2013 rf; 2May2013 plsp; 2May2013 jab For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or