Elymus australis Scribn. & C.R. Ball

Scientific Name: Elymus australis Scribn. & C.R. Ball

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | ELAU2 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Graminoid |

| Native Locations | ELAU2 |

Plant Guide

Uses

Southeastern wildrye is a native, robust, upright, cool-season grass that tolerates a variety of soils and cultural conditions. It is relatively short-lived and does not tolerate frequent mowing. It is compatible with native warm-season grasses and wildflowers in seed mixes. Beneficial characteristics include rapid and high germination rates; long-term seed viability; suitability for slope, riparian and critical area stabilization; and tolerance of well-drained sandy to waterlogged soils. Southeastern wildrye is a tool for private and public land managers developing plans that combine the benefits of wildlife habitat with production agriculture. Restoration and Soil Stabilization: The use of native grasses for revegetation has increased with the increased availability of plant material and the recognition that native species are important in the restoration of biological diversity (Knapp and Rice, 1996). Southeastern wildrye seed germinates quickly and in high percentages (70%) making it useful for roadsides, stabilization of slopes and other highly erodible areas. Public awareness of the health of the Chesapeake Bay and Mississippi River Basin watersheds has increased the desire to reduce the environmental impacts from synthetic inputs. One of southeastern wildrye’s strongest attributes is that it requires little or no fertilization for establishment and maintenance; making it ideal for restoration plans seeking to protect water quality. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park primarily uses grasses to stabilize steep roadsides. Effective slope stabilization is achieved by hydro-seeding southeastern wildrye, hard fescue (Festuca brevipila), Chewing’s fescue [Festuca rubra L. ssp. fallax (Thuill.) Nyman], red fescue (Festuca rubra), and annual ryegrass (1TLolium multiflorum) with1T other native warm season grasses and wildflowers at the rate of 260 lbs of seed of per acre in the early autumn or spring. Southeastern wildrye provides winter soil coverage when many other plants are dormant. Seed stored under optimal conditions (less than 50º F and 30% relative humidity) remains highly viable for up to 10 years (Observations at the National Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, MD). A 1:1:1 seed mix of the wildryes Canada, Virginia and riverbank seeded (20 lbs. /acre) with fringed bromegrass (Bromus ciliatus) (9 lbs. /acre) and fowl bentgrass (Poa palustris) (0.5 lbs. /acre) provides quick dense cover for erosion control on up to a 2% grade (Salon 2006). Southeastern wildrye has the potential to function similarly to the other wildryes. Wildlife: Various beetles and butterfly larvae feed upon members of the genus and spiders commonly build webs among the spikelets. Phorbia flies eat patches of fungi spreading the beneficial fungal spores from one grass to the next. Ground-dwelling sparrows consume wildrye seed. As the plant matures and lodges (fall over), excellent habitat is created for ground-nesting birds such as bobwhite quail. Deer do not graze on wildrye, as grasses are not a primary food. They will eat grass when it is young and tender, but tend to avoid it after it is older unless it is their only choice for food. Forage: Southeastern wildrye is a good cool-season forage, with high crude protein (13-19%), low neutral detergent fiber (45-55%), and low acid detergent fiber (25-35%) on unfertilized stands (Rushing 2012). Dry matter yields of more than 3 tons/acre can be achieved. Rotational grazing is recommended in order to maintain forage quality (harvest or graze every 20-30 days) and quantity. High innate nutritional content makes southeastern wildrye a great cool-season option for those interested in a year-round grazing system using only native species.

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Description

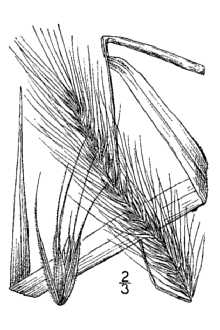

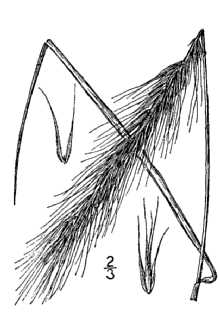

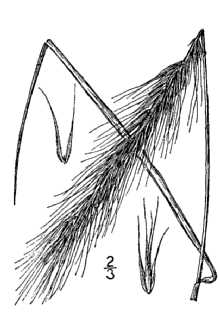

General: Originally described as a variety of Canada wildrye, southeastern wildrye at times has been classified as a variety of Virginia wildrye (e.g. Hitchcock 1951), but more recently is recognized as a distinct species (Barkworth et al. 2007). Southeastern wildrye is a 4 foot tall, cool season, clump-forming, perennial grass. As with its domestic relatives, wheat and rye, seeds are borne in terminal spikes (ears). Figure 1: Comparison of Virginia and southeastern wildrye spikes. Photo by Sara Tangren. Figure 1 shows the Virginia wildrye spikes (left), narrow (up to 1 inch) with the spikelets appressed tightly along the central axis. The spikes are often enclosed in the uppermost leaf. Southeastern wildrye spikes (right) are wide (up to 2 inches) with the spikelets held at a more open angle from the central axis of the spike. The long awns also contribute to the width and overall appearance of the spike. Southeastern wildrye spikes are usually exserted well beyond the uppermost leaf. Mature, upright, spikes are fully emerged above the foliage, 1 to 2 inches wide, and up to 8 inches long. Southeastern wildrye flowers from May through July and is largely self- pollinated and occasionally pollinated by wind. Flowering usually occurs two to four weeks after Virginia wildrye (Barkworth 2007). The evenly distributed, dull green leaves are about one-third to two-thirds of an inch wide. . Southeastern wildrye increases in width by tillers, it does not spread from rhizomes, and the root system is fibrous. Fibrous roots attach firmly to soil particles, making them especially effective in preventing soil erosion. Figure 2: Comparison of Virginia and southeastern wildrye spikelets. Photo by Sara Tangren. Figure 2 shows the Virginia wildrye spikelets (left), shorter (0.4 to 1.0 inches) than southeastern wildrye spikelets (right, 0.9 to 1.7 inches). Southeastern wildrye is most closely related to early and Virginia wildryes (Elymus macgregorii and Elymus virginicus) and occasionally hybridizes with them (Barkworth, 2007) Distribution: Southeastern wildrye distribution from USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database Southeastern wildrye has a very broad distribution range and wide adaptability. For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Southeastern wildrye can be found in woodland edges, open woods, temporary and permanent meadows, thickets and open grasslands, sometimes spreading into old fields and roadsides (Barkworth 2007).

Adaptation

Southeastern wildrye is tolerant of a wide range of conditions from moist to dry soil, full sun to part shade, (plants grown in full sunlight tend to be more robust than those grown in shade) coarse to fine substrate, early successional to mature meadow communities, and acid to neutral soil pH’s, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Elymus australis Scribn. & C.R. Ball.,

Establishment

Seed Bed Preparation: To ensure successful establishment, make sure moderate to high levels of potassium and phosphorous are present in the soil (root and crown development). Establishment year nitrogen can promote weed competition; therefore, nitrogen applications should not be made until the following year, once plants have matured. Refer to the test recommendations prior to establishment to address any required amendments. In order to limit weed pressure, allow weeds to germinate and grow to the 2 – 4 leaf stage before treatment with a non-selective herbicide such as glyphosate. If the field has been fallow and heavy weed pressure is anticipated it may be necessary to repeat this step multiple times. Prepare a clean firm, weed free seedbed by disking, harrowing, and firming the seedbed with a cultipacker or roller prior to establishment. Seed Pre-treatment (stratification): Seed viability and longevity are maximized by cold storage (<50P oPF and 30% relative humidity). Seed stored this way will germinate within 7 to 10 days of exposure to moisture. More rapid uniform germination can be promoted with 7 days of cold, moist stratification. Extended cold, moist stratification will lead to premature germination (Observations at the National Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, MD). Sowing: Wildrye seeds can be sown at any time of the year but germination and growth will only occur during cool, moist weather. Early fall establishment is recommended, however spring sowing can be successful if early enough in the season to avoid heat stress. Fall establishment will allow for root development prior to the winter, and vernalization for spring seed germination. Optimum soil temperatures for sowing are between 60-68P oPF. Southeastern wildrye should be planted at a rate of 20 lbs of pure live seed (PLS) per acre drilled. Broadcasting rates are higher (30 lbs/A) and should be cultipacked following sowing to ensure contact between seed and soil. Seed should be sown ¼ to ½ inch deep, rain or irrigation may be used to firm the seedbed and is essential for germination. When spring sown, plants are capable of reaching 5 inches tall within 30 days of germination. Plants reach full height and reproductive maturity in their first year. Seed Harvest: Seed can be collected from mature plants when the inflorescence is no longer green (~15% moisture). In Maryland this occurs early to mid September. Prior to any mechanical seed cleaning, dry in a cool area (at temperatures less than 70º F) for 2-4 weeks. Paper bags are ideal for small lots; large lots should be spread on a tarp. A fan will greatly accelerate this process. Seed Cleaning: The type of equipment to be used to broadcast the seed determines the type of cleaning. The long awns of southeastern wildrye (figure 2) may clog (bridge) the tubes of most no-till drills and planters. The time that it takes for awn removal is variable and should be checked closely until the desired amount of awn removal is reached. Planting rates should be adjusted (based on pure live seed – PLS) to accommodate reduced germination when establishing debearded southeastern wildrye. The long awns will not interfere with broadcast by hand or with hydro seeding, so de bearding is not necessary. Use a three screen seed cleaner to separate debearded seed from chaff and weed seed.

Management

Fall-season seedling growth and vigor can be fairly slow to moderate. Following a fall planting, above-ground biomass will not significantly accumulate until the following spring. However, upon successful establishment and proper management, plants will begin to tiller and develop crowns for regeneration and carbohydrate storage. Southeastern wildrye can withstand light grazing. Rotational grazing is recommended for preservation of mature stands. Plants should not be defoliated (clipped or grazed) lower than 5 to 6 inches, in order to prevent weed competition and promote vegetative growth (more nutritious and greater palatability). Defoliation should occur every 20 to 30 days in order to maintain high forage quality and quantity. If haying, harvest prior to jointing (seed head development) to capture highest forage quality. One harvest can be expected, as summer heat forces the plants into dormancy. Plants are nitrogen responsive, therefore traditional approaches for hay management in regards to nutrient removal can be applied to southeastern wildrye. Herbicide may be necessary for seed production or roadside situations. Oryzalin is an effective broad spectrum pre-emergent herbicide for established stands. Broadleaf weeds can be controlled with 2, 4,-D amine, MCPP-p, dicamba, or clopyralid. Yellow nut sedge can be a stubborn weed in moist soils, halosulfuron provides good control.

Pests and Potential Problems

Diseases: Plants established after a glyphosate treatment may develop fusarium head blight (Figure 3), a condition which affects seed quality but not foliage (Fernandez 2005). Figure 3: Fusarium Head Blight symptoms on seed. Photo by Sara Tangren. Rust (Puccinia spp.) has been observed on leaves late in the season, after seed heads have emerged and matured.

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

The entire tribe of grasses, of which southeastern wildrye is a part, is prone to hybridize and form new species, some of which are fertile and some are not. The ecological consequences of moving Elymus species outside their natural range are difficult to forecast.

Control

The authors have not observed any incidence of southeastern wildrye becoming invasive. Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective.

References

Barkworth, M.E., J.J.N. Campbell & B. Salomon (2006). Elymus L. In: Flora North America Editorial Committee (Eds.). Flora of North America North of Mexico Vol. 24: 288-343. Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part) Poaceae, part 1. Oxford University Press, New York. Manuscript. www.3Therbarium.usu.edu/webmanual3T (accessed on 5/01/09). Bultman, T., J. White, T. Bowdish, A. Welch and J. Johnston, 1995. Mutualistic Transfer of Epichloë Spermatia by Phorbia Flies. Mycologia, 87:2 182-189. Fernandez, M.R., F. Selles, F. Gehld, M. DePauw and R.P. Zentner. 2005. Crop Production Factors Associated with Fusarium Head Blight in Spring Wheat in Saskatchewan. Crop Sci. 45: 1908–1916 Knapp, E.E. and K.J. Rice. 1996. Genetic Structure and Gene Flow in Elymus glaucus (blue wildrye): Implications for Native Grassland Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 4(1): 1-10. Rushing, J.B. 2012. Evaluation of wildrye (Elymus spp.) as a potential forage and conservation planting for the southeastern United States. Mississippi State University Library, Mississippi State, MS 39762. Sanderson, M.A., R.H. Skinner, J. Kujawski, M/ van der Grinten. 2004. Virginia Wildrye Evaluated as a Potential Native Cool-Season Forage in the Northeast USA. Crop Science 44: 1379-1384. Salon, P.R and M. van der Grinten. 2007. Compatibility of a mixture of Canada, Virginia and riverbank wildrye seeded with seven individual species of native and introduced cool season grasses. . The Fifth Eastern Native Grass Conference, Harrisburg, PA. October 10-13 2006. 1p. Prepared By: Shawn Belt, USDA, NRCS Norman A. Berg National Plant Materials Center, Brett Rushing Mississippi State University, and Sara Tangren. Citation Belt, S., B. Rushing, S. Tangren. 2013. Plant Guide for Southeastern wildrye (Elymus glabriflorus). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Norman A. Berg National Plant Materials Center. Beltsville, MD 20705. Published March 2013. Edited: [29jan2013sb, 28jan2013br, 2feb2013st] For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or