Darwinia exaltata Raf.

Scientific Name: Darwinia exaltata Raf.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | DAEX4 |

| Group | Dicot |

| Life Cycle | AnnualPerennial, |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herbSubshrub, |

| Native Locations | DAEX4 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Common Names: hemp sesbania, coffee-bean, danglepod, coffeeweed, Colorado River-hemp, peatree, sesbania Scientific Names: Sesbania exaltata (Raf.) Rydb. ex A.W. Hill, Sesbania herbacea auct. N.Amer. Darwinia exaltata Raf. (basionym), Sesban exaltatus (Raf.) Rydb., Sesbania macrocarpa Muhl., nom. nud.

Uses

Forage: There is some debate regarding the toxicity of the saponins in Sesbania spp. (Powell, et al. 1990). Allen and Allen (1981) reported that ingestion of the plant poisoned cattle in Florida and Texas, and Everest et al. (2005) observed that ingestion of the saponins in the plant can result in death. However, Evans and Rotar (1987) reported that leaflets and seeds of bigpod sesbania were not toxic. They also observe that saponins are not harmful to ruminants when ingested. Nevertheless, all authors agree Sesbania spp. are potentially toxic, whether caused by saponins or a high Ca: P ratio during the reproductive growth stage of the plant (Evans and Rotar, 1987). Despite this plant’s potential toxicity, it is very palatable to cattle, and has good forage quality and nutritional value. The seed is especially attractive to livestock when there are few other food sources. Its vegetation contains 31% crude protein (Evans and Rotar, 1987) at its vegetative stage, falling to 11.2% at its seed production stage (Bosworth, et al., 1980). Cover crop/green manure: Bigpod sesbania is grown mainly for use as a soil-improving crop (Duke,1983). It can produce 2 to 3 ton/acre in 75 days and 90–130 lbs/acre N in above ground biomass (Wang and Nolte, 2010). It was once used extensively as a cover crop in citrus groves (Allen and Allen, 1981) and by cotton and truck crop growers in California (Evans and Rotar, 1987). In Sinaloa Mexico, bigpod sesbania was found to have higher yield, require less weed cultivation, and was less susceptible to pests than cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) (Evans and Rotar, 1987). Bigpod sesbania tends to sprawl and can be supported with sorghum sudangrass when grown in a warm-season mixture. Growing bigpod sesbania onto a support such as sorghum sudangrass will help the plant increase height, thereby optimizing plant leaf position and improving photosynthesis (Baligar et al., 2009). Wildlife: Bigpod sesbania attracts beneficial insects such as lady beetles and parasitic wasps. The wasps are attracted to glands that secrete sugars on the leaf margins (ASI, 2013). The seeds persist throughout winter and early spring and are an important food source for quail, turkeys, mallards, limpkins, American pintails, quail, and eastern mourning doves (Graham, 1941). It is sometimes sown with browntop millet (Urochloa ramosa) in wildlife plantings (ASI, 2013).

Ethnobotany

Many species within the genus are used for fiber production as a substitute for hemp. Its fiber was used by the Yuma Indians for production of nets and fishing line (Evans and Rotar, 1987) and the stems can be used for paper production (Allen and Allen, 1981).

Status

Bigpod sesbania is a native species in the United States, but is considered a noxious weed in some states. Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Description

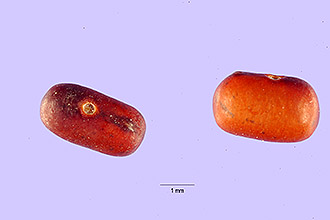

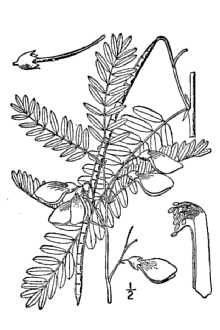

General: Bigpod sesbania is a semi-woody, native, perennial where it can be grown yearlong in frost-free zones or as an annual warm-season legume where it is frost-killed. It has smooth, green, tapering stems that become woody with age. Although it only has a few wide-spreading branches, it can grow 3–10 ft tall. The Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Guide former species name exaltata means extremely tall, and refers to the plant’s height. The alternately arranged 30 cm leaves are even-pinnately compound, with approximately 20–70 oppositely arranged leaflets. Leaflets are 0.75–2.5 cm long, with smooth margins and a pointed tip. They are somewhat hairy or waxy underneath. There are 2 to 6 stalked, bell-shaped flowers occurring on a 2–8 cm elongated inflorescence growing from the leaf axil (where the leaf stalk joins the stem). The flower has yellow or yellow-orange petals that are streaked or spotted with purple. The flower tube is 3–4 mm long and 4–5 mm wide. The pea-type flower’s upper petal is 1.5 cm long, and the wing and keel petals are shorter. Its linear seedpod is 10–20 cm long and 3–4 mm wide, smooth, jointed, curved, 4-sided, and tipped with a small beak. The seedpod can contain 30 to 40 seeds. The seeds are mottled with orange, green, and brown. It can be sometimes confused with partridge pea (Cassia fasciculata) however; partridge pea has fewer (16–30) leaflets per leaf. It may live up to 20 years (FAO, 2007) in regions where it can survive as a perennial. Distribution: In the United States, bigpod sesbania grows from New York to the Southeast, and southwest to Texas and California. It is also found in Mexico and Central America. Historically, it was once popular as a green manure crop in Arizona and Southern California (Evans and Rotar, 1987). For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Bigpod sesbania grows in ditches, disturbed sites, and along railroads, river banks, and roadsides. It is commonly found in cropland, often growing in wet soils, sandy sites, alluvial soils along sloughs, on the sand bars of streams, and in the coastal plain. It grows best in areas with hot summers and low humidity (Evans and Rotar, 1987).

Adaptation

Generally, bigpod sesbania is adapted to tropical and subtropical areas (ASI, 2013), growing where an annual mean temperature is 55–82°F (12.5–27.8°C). It was found unable to adapt to cool night temperatures in the Northwestern US (Evans and Rotar, 1987) and it is killed by frost (ASI, 2013). It can tolerate drought and grows at higher elevations than crotalaria (ASI, 2013). It grows in soils with a pH from 4.5–7.2 (ASI, 2013). It grows extremely well in the alluvial clay soils of the lower Mississippi River Valley (Bryson, 1990).

Establishment

The seed should be scarified before seeding and inoculated with “Special Culture 1 for Sesbania” (ASI, 2013). Plant in full sun in late spring at 10–25 lbs/acre, and sow ¾ in deep (ASI, 2013). The plant grows rapidly from July to August. McWhorter and Anderson (1979) observe that 50% of the plant’s growth occurs between 8 to 13 weeks after date of planting. Bigpod sesbania can tolerate some flooding once it reaches seedling stage but it should not be sown in standing water (Evans and Rotar, 1987) as it will not grow in flooded conditions. It is shallow-rooted and requires more water than sunn hemp or cowpea so may require irrigation until established (ASI, 2013). It will remain green until first frost.

Management

Traditionally bigpod sesbania has been used in rotations with vegetable or grain crops. Over a 5-year period the yield of a barley crop was increased by preceding it with bigpod sesbania (Evans and Rotar, 1987). When used in rotations it is recommended to terminate bigpod sesbania early, after 6–9 weeks of growth and before seed-set to avoid weediness (NOFA, 2013). It can tolerate high mowing, and should be mowed before incorporation into the soil (ASI, 2013). Weeds should be cultivated, as bigpod sesbania does not compete well with weeds (ASI, 2013). Fields of bigpod sesbania may be flooded to control weed and insect populations (Evans and Rotar, 1987). The stand can be maintained as a perennial if the seed is disked into the soil in the fall (Graham, 1941). Once bigpod sesbania grows 12 cm tall, post emergent herbicides are ineffective for control (McWhorter and Anderson, 1979). Infestations of bigpod sesbania in soybean fields are particularly difficult to control because both plants are broadleaved legumes and are sensitive to the same herbicides (Evans and Rotar, 1987).

Pests and Potential Problems

Bigpod sesbania is infested by the cowpea aphid, banded-winged whitefly, and the alfalfa caterpillar, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Darwinia exaltata Raf.., The larvae of sesbania clown weevils attack roots and nodules, and adults defoliate the plant, Selenis monotropa moths attack both this plant and soybean (Evans and Rotar, 1987), When grown in infertile soil, it can be affected by root-knot nematodes (Graham, 1941),

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

Bigpod sesbania may easily become an invasive weed. It is a serious weed in soybean, cotton, sweet potatoes, and rice (Evan and Rotar, 1987). No pre or post-emergent herbicide has provided season-long control (Bryson, 1990). Its use in the Southwest has been discontinued because of its weed-like tendencies (Evan and Rotar, 1987). Bigpod sesbania can grow over the tops of cash crops like soybean. Populations greater than 5,500 plants/ha began to reduce soybean yields (McWhorter and Anderson, 1979). Because it tends to colonize the banks of waterways and distribute seed by water, it may be easily spread over a large area via watercourses. It can be an opportunistic plant in disturbed, less flooded, higher elevation sites (Meert and Hester, 2009). Using bigpod sesbania as a cover before cool-season vegetable crops can increase sting nematode populations and reduce yields in subsequent crops (ASI, 2013). The plant does not contain toxic sesbanimides (Powell et al., 1990), however it does contain potentially harmful levels of saponins.

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Bigpod sesbania flowers from March to October in Arizona (Evans and Rotar, 1987) or approximately 45–50 days after seeding (ASI, 2013). It is rapid growing, quick to set seed, and will continue to produce seed over a long period. Plants are self-compatible, and seed size and number of fruit are the same for self and out-crossed reproduction (Marshall et al., 2005). The seedpods will remain on the plant throughout winter but they shatter easily after maturity, making machine harvesting difficult (Evans and Rotar, 1987). The seed coat is impermeable. Approximately one-third of the seeds produced are hard seeds (McWhorter and Anderson, 1979) and may not germinate consistently at time of planting. These seeds may grow later with subsequent crops, becoming difficult to manage. Evans and Rotar (1987) found that 29% of seeds survived after being buried in the soil for 2.5 years. Seeds have been found to be non-toxic (Evans and Rotar, 1987). There are approximately 48,000 seeds/lb (Turner, n.d.). Small amounts of seed are available through commercial sources.

References

Agricultural Sustainability Institute (ASI) 2013. Sesbania. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program (SAREP). UCDavis College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. http://www.sarep.ucdavis.edu/database/covercrops (accessed 18 Jan. 2013). Allen, O.N. and E.K. Allen. 1981. The leguminosae: a source book of characteristics, uses, and nodulation. The Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison. Baligar, V.C., N.K. Fageria, A.Q. Paiva, A. Silveira, A.W.V. Pomella, R.C.R. Machado. 2006. Light intensity effects on growth and micronutrient uptake by tropical legume cover crops. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 29:1959–1974. doi: 10.1080/01904160600927633 Bosworth, S.C., C.S. Hoveland, G.A. Buchanan, and W.B. Anthony. 1980. Forage quality of selected warm-season weed species. Agronomy Journal. 72:1050–1054. https://www.agronomy.org/publications/aj/abstracts/72/6/AJ0720061050 (accessed 25 Jan. 2013) Bryson, C.T. 1990. Interference and critical time of removal of hemp sesbania (Sesbania exaltata) in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Technology. 4:833–837. Duke, J.A. 1983. Sesbania. Handbook of energy crops NewCROP (New Crops Resource Online Program), Purdue Univ. Center for New Crops and Plant Products. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/Crops/Sesbania.html (accessed 18 Jan. 2013). Evans, D.O., and P.P. Rotar. 1987. Sesbania in agriculture. Westview Press, Boulder, CO. Everest, J.W., T.A. Powe Jr., and J.D. Freeman. 2005. Poisonous plants of the Southeastern United States. Alabama Cooperative Extension. ANR-975. http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs/A/ANR-0975/ANR-0975.pdf (accessed 25 Jan. 2013). Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2007. Sesbania exaltata data sheet. Ecocrop. http://ecocrop.fao.org/ecocrop/srv/en/home (accessed 16 Jan. 2013) Graham, E.H. 1941. Legumes for erosion control and wildlife. USDA Misc. Publ. No. 412. Wash. D.C. https://play.google.com/books Marshall, D.L., N.J. Abrahamson, J. J. Avritt, P.M. Hall, J. S. Medeiros, J. Reynolds, M.G.M. Shaner, H.L. Simpson, A.N. Trafton, A. P. Tyler, and S. Walsh. 2005. Differences in plastic responses to defoliation due to variation in the timing of treatments for two species of Sesbania (Fabaceae). Annals of Botany 95:1049–1058. McWhorter, C.G., and J.M. Anderson. 1979. Hemp sesbania (Sesbania exaltata) competition in soybeans (Glycine max). Weed Science 27(1):58–64. Meert, D.R., and M.W. Hester. 2009. Response of a Louisiana Oligohaline marsh plant community to nutrient availability and disturbance. Journal of Coastal Research. 10054:174–185. doi: 10.2112/SI54-014.1 Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA). 2013. Sesbania. http://www.nofanj.org/cover-crop-listings/sesbania (accessed 25 Jan. 2013) Powell, R.G., R.D. Plattner, and M. Suffness. 1990. Occurrence of sesbanimide in seeds of toxic Sesbania species. Weed Science. 38:148–152. http://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/24279/PDF (accessed 22 Jan. 2013) Wang, G. and K. Nolte. 2010. Summer cover crop use in Arizona vegetable production systems. Arizona Cooperative Extension. The University of Arizona College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Publication #AZ1519. http://cals.arizona.edu/pubs/crops/az1519.pdf (accessed 18 Jan. 2013) Prepared By: Christopher M. Sheahan; USDA-NRCS, Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May, New Jersey. Citation Sheahan, C.M. 2013. Plant guide for bigpod sesbania (Sesbania exaltata). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center. Cape May, NJ. 08210. Published 02/2013 Edited: 5/15/2014jad For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or

Conservation

District at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/ and visit the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov/ or the Plant Materials Program Web site http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov. PLANTS is not responsible for the content or availability of other Web sites.