Bromus tectorum L. var. hirsutus Regel

Scientific Name: Bromus tectorum L. var. hirsutus Regel

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | BRTEH |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Annual |

| Growth Habits | Graminoid |

| Native Locations | BRTEH |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Downy brome, downy bromegrass, downy chess, early chess, slender chess, drooping chess, junegrass, and bronco-grass

Uses

Erosion Control: due to being a winter annual species with a shallow root system, cheatgrass is considered a poor erosion control plant particularly during periods of extended drought. Invasive to Noxious Traits: Cheatgrass or downy brome is native to the Mediterranean region. In Europe, its original habitat was the decaying straw of thatched roofs. ‘Tectum’ is Latin for roof, hence the name Bromus tectorum, ‘brome of the roofs’. Introduced into the United States in packing materials, ship ballast and likely as a contaminant of crop seed, cheatgrass was first found in the United States near Denver, Colorado, in the late 1800s (Whitson et al. 1991). In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, it spread explosively in the ready-made seed-beds prepared by the trampling livestock hooves of overstocked rangelands. Disturbance associated with homesteading and cultivation of winter wheat also accelerated its spread and establishment. By the 1930’s, cheatgrass was becoming the dominant grass over vast areas of the Pacific Northwest and the Intermountain West regions and the “worst” western range weed. Hitchcock (1950) Cheatgrass has developed into a severe weed in several agricultural systems throughout North America, particularly western pastureland, rangeland, and winter wheat fields. It is now estimated to infest more than 41 million hectares (101 million acres) in western states (Mack 1981). Winter wheat growers in the western United States proclaim it as their worst weed problem. In the Palouse winter wheat country of the Pacific Northwest, at high density, it reduces wheat yields by an average of 27% (FICMNEW, 1997). It can reduce seed yield of winter rye as much as 33%. In winter wheat and alfalfa fields, it is especially troublesome, because of its ability to reproduce prior to crop and hay harvesting (Peepers 1984). It is an aggressive invader of sagebrush, pinyon-juniper, mountain brush and other shrub communities, where it often completely out-competes native grasses and forbs. Approximately five million hectares of overgrazed rangeland in Idaho and Utah are covered by almost pure stands of cheatgrass (FICMNEW 1997). Serious problems with downy brome have been reported in the New England nursery trade and in orchards (Morrow & Stahlman 1984). Stands of cheatgrass on western rangeland are highly flammable in late spring through early fall after maturation, which usually occurs long before native species mature and enter summer and autumn dormancy. Consequently, its presence, in altering the timing and occurrence of range and forest fires, negatively impacts other species. Livestock: Although cheatgrass provides good quality forage early in the season, the plants mature quickly; initially turning reddish before completely curing to a tan- buff color. Forage yields fluctuate widely with changes in annual precipitation. The best forage quality is in late winter to mid spring and it must be grazed early in the growing season. Moreover, under drought situations the presence of cheatgrass causes rapid depletion of early season soil moisture, thus serving to out-compete, retard or prevent the establishment of perennial grasses (Welsh 1981). Mature plants are unpalatable, the characteristic drooping seed heads becoming brittle as the plant dries, shattering upon disturbance and disseminating the sharp-tipped seeds with their barbed awns. These sharp-tipped seeds work their way into the eyes, nostrils, mouths, and intestines of grazing animals. Put succinctly by Aldo Leopold (1949), he writes “to appreciate the predicament of a cow trying to eat mature cheat, try walking through it in low shoes. All field workers in cheat country wear high boots.” Leopold was perhaps one of the first authors to bring to the general public an awareness of the impact of cheatgrass in the west. In his essay “Cheat Takes Over,” he addresses the ecological implications of its establishment with clarity and humor. His list of negative impacts and noxious characteristics are: • replacement of rich and useful native bunchgrasses and wheatgrasses with the inferior cheat; • prickly awns that, when mature, cause cheat-sores in the mouths of cows and sheep; • extreme flammability of cheat-covered lands that results in burn-back of winter forage such as sagebrush, bitterbrush, and perennial grasses, and destruction of winter cover for wildlife; • degradation of hay following invasion of alfalfa fields; and • blockading of newly-hatched ducklings from making the vital trek from upland nest to lowland water. Vectors: Overgrazing and misuse of western rangelands has resulted in trampling of native bunchgrasses and destruction of the soil surface and sometimes cryptogam layer, resulting in an increase in evaporation of soil moisture and reduction of bunchgrass population. Such disturbance favors the invasion of cheatgrass, whose seedlings become established during fall through late winter before the principal germination and growth period of native taxa. Homesteading and cultivation of winter wheat, beginning with the railroad boom of the 1880s, disturbed the land even further, and accelerated the introduction and establishment of cheatgrass. Cultivation of land for winter wheat prepares a seedbed. The lack of the use of selective herbicides for the control of cheatgrass has aided its increase and spread. The barbed awns of the florets penetrate or adhere readily to fur or clothing. When vehicles are driven across cheatgrass- infested land, seeds become lodged in clothing, tire treads, in cracks and crevices, and in mud of tires and bumpers, to be dislodged perhaps hundreds of miles distant. Since its introduction, cheatgrass has been spread far and wide by livestock, by trains and other vehicles, and by wildlife and livestock. Seeds, maturing before harvest of alfalfa and winter wheat, contaminate hay and grain. Wildlife: Deer and elk make some use of cheatgrass in late winter to early spring while it is green and prior to other grasses and forbs beginning growth. It seems to be very important food, cover and nesting habitat for Hungarian partridge and chukar. Canada geese graze cheatgrass heavily in fall, winter and early spring.

Status

Consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status.

Description

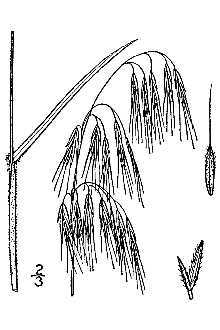

General: Grass Family (Poaceae). Cheatgrass is an annual or winter annual, softly downy to short-hairy throughout, and generally 10- 60cm (4- 24 in) tall. Stems are solitary or in a few-stemmed tuft. Ligules are short (usually 1- 2 mm long), membranous, and fringed at the top; auricles are lacking. Leaf blades are up to 20 cm (8 in) long, flat, relatively narrow, usually 2- 5 mm wide (1/8- 3/16 in), and generally long-ciliate near the base. The roots are fibrous and usually quite shallow; the plants do not root at the nodes. The inflorescence is a soft and drooping, much-branched, open panicle, usually becoming a dull red- purple color as it matures to a tan- buff color when fully cured. Spikelets are about 1.5- 2.0 cm (0.6- 0.8 in) long with 3- 6 florets. Florets are 12- 19 mm (1/2- 3/4 in) long, tapering to sharp points. The glumes are shorter than the florets, the first 1-veined and the second 3-veined. Lemmas are sharply tipped, glabrous to densely hairy, more-or-less rounded on the back, and with a nearly straight awn that is 7- 18 mm (3/8- 5/8 in) long. Flowering occurs from April to mid June depending on climate and location. Reproduction is by seed. Germination occurs in fall through winter to early spring, depending on the climate and rainfall (Hickman 1993; Gleason & Cronquist 1991; Cronquist et al. 1977; Muenscher 1955; Uva et al. 1997).

Adaptation

Cheatgrass grows in rainfall areas receiving 6- 22 inches or more. It does particularly well under conditions where rainfall occurs in fall, winter and early spring. During periods of multiple year drought, it may almost disappear from the plant community only to return in very lush stands as moisture conditions improve. Cheatgrass prefers well drained soils of any soil texture. It is not well adapted to saline or sodic soil conditions or soils that are too wet. Cheatgrass can be found at almost any elevation, but it does particularly well at elevations ranging from 500- 6,000 feet.

Distribution

Cheatgrass is one of the most widespread introduced annual grasses in the North America, occurring in all 50 states as well as in most of the Canadian provinces and also in parts of Mexico. It is most common where annual rainfall ranges from 15-55 cm (6- 22 in) and autumn rainfall ranges from 5-12 cm (2- 6 in) (Peepers 1984). It is a weed of roadsides, cropland, hayland, pastureland, rangeland and waste places, usually occurring on dry, sometimes weakly alkaline, clayey to loamy to sandy or gravelly soils. Cheatgrass is especially common in the western states including the Columbia Basin, Snake River Basin and the Great Basin (Morrow & Stahlman 1984). Uncommon or sporadic in the southeastern part of the United States, it is abundant over large areas of sagebrush plant communities, where whole landscapes are lush green, turning red- purplish by the developing inflorescences, then a tan- straw- buff color as the plants mature and cure. Hitchcock (1950) For current distribution, consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site.

Establishment

This species is not recommended for seeding, , Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Bromus tectorum L. var. hirsutus Regel.

Control

Contact your local extension specialist or county weed specialist for assistance on recommendations for cheatgrass control in your area. Tillage and chemicals are the most common control methods. When using chemicals, it is important to always read and follow label and safety instructions. Trade names and control measures that appear in this document are only to provide specific information. USDA, NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Environmental and Mechanical: Environmental practices, which minimize the further spread of cheatgrass, are suggested by knowledge of the circumstances, which have accompanied its spread. Vehicles, clothing, camp gear, and pets should be cleaned of adhering seed after driving, camping, and walking in cheatgrass-infested areas. Excessive roadside and rangeland disturbance should be avoided. In cultivated fields, mowing cheatgrass before seeds are formed and clean cultivation assist in control. Infested meadows and pastures can be harrowed while seedlings are small (Muenscher 1955). In cropland and hayland, the best control is often achieved by fallowing or planting continuous spring crops for two or more years (Kennedy et al. 1989). Biological: Soil bacteria which cause crown rot may be a potential biological control for cheatgrass in the arid environment of western North America (Grey et al. 1995). The crown rot causing soil bacteria has been found to produce a toxin that is specific for cheatgrass and related species. Studies have shown that these bacteria can be used to suppress the growth of cheatgrass, thus resulting in substantial increases in winter wheat yields (Kennedy et al. 1989). Applications of a strain (D7) of Rhizobacterium have been shown to selectively suppress cheatgrass in winter wheat test plots by means of a phytotoxin produced by the bacteria (Tranel et al. 1993), apparently by inhibition of root elongation. Chemical: Non-selective herbicides are presently the primary chemical available for control of cheatgrass. Since non-selective herbicides can kill all vegetation they contact, not just the problem weed, care must be taken that they do not contact desirable plants. The chemical fluazifop has been shown to prevent seed formation in cheatgrass, most successfully when applied early in the reproductive phase (Richardson et al. 1987. Metribuzin or Metribuzin plus terbutryn, fall-applied, have succeeded in reducing cheatgrass infestations and increasing wheat yields. The combination results in better control. Sulfonylurea herbicides have been shown to increase winter wheat yields when used for cheatgrass control. Other herbicides that have been recommended for cheatgrass management include glyphosate, bromacil, imidazolinone and tebuthiuron. Formulations containing glyphosate are marketed as JURY, RATTLER, ROUNDUP, and RODEO. Those containing bromacil are sold as HYVAR X and HYVAR X-L. Those containing imidazolinone are sold as Plateau. Tebuthiuron is sold as SPIKE 80W. Glyphosate controls cheatgrass by inhibition of biosynthesis of amino acids. It is applied to above ground parts, since the active ingredient is adsorbed and made inactive by soil particles. Following absorption, glyphosate is translocated to underground structures and should thus be applied during active growth. Growth is inhibited soon after application, and foliar chlorosis and necrosis are seen within 10-20 days. Contact with formulations of glyphosate should be avoided. Ingestion requires emergency medical attention. Bromacil inhibits photosynthesis. It is readily absorbed through the root system and is then translocated to foliage. It is applied as a spray just before or during the period of active growth, preferably when rain can be expected for soil activation. Application near desirable plants or grazing of cattle in treated areas should be avoided. After the herbicide has been carried into the root zone by rain, leaf chlorosis and defoliation occur within a week. Contact with bromacil may irritate eyes, nose, throat, and skin. In case of contact, flush eyes copiously with water and wash skin with soap and water. Get medical attention if irritation persists. Tebuthiuron is a pre- and post-emergence herbicide used for total control of vegetation. A small amount of the herbicide in contact with roots of desirable plants may kill them. It produces browning of vegetation within one week, which suggests that it acts through photosynthesis inhibition. It is absorbed principally through the roots, and is readily translocated. For best results it should be applied before spring growth begins. At least one inch of rainfall is needed to activate the herbicide and place it in the seed germination zone, so it should be applied before the predominant portion of annual rainfall occurs. It may not be fully effective on clay soils or those high in organic matter. Tebuthiuron should not contact skin, clothing, or eyes (causes eye irritation). If it gets on skin or in eyes, wash with plenty of water; if swallowed, or if breathing difficulty develops from inhalation, get emergency medical attention. Imidazolinone, sold as Plateau is a pre- and post-emergence herbicide used for partial to total control of vegetation. Plateau herbicide may be used for control of brome grass species and tall fescue. It can be used for the release of most other wheatgrasses, native grasses, wildflowers and certain legumes. It is readily absorbed through leaves, stems, and roots and is translocated rapidly throughout the plant, with accumulation in the meristematic regions. Treated plants stop growing soon after spray application. Adequate soil moisture is important for optimum herbicide activity. When adequate soil moisture is present, it will provide residual control of susceptible germinating weeds. Activity on established weeds will depend on the weed species and rooting depth. Post emergence application is the method of choice in most situations, particularly for perennial species. It may be applied in the dormant or growing season for weed control. Tolerance of desirable grass species to Plateau herbicide may be reduced when grasses are stressed due to insect damage, disease, environmental conditions, shade, poorly drained soils or other causes. It should not be applied to newly seeded or sprigged grass stands, unless stated in label.

References

Abrams, L. 1923. An illustrated flora of the Pacific States. Vol. 1. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. Albee, B.J., L.M. Shultz, & S. Goodrich 1988. Atlas of the vascular plants of Utah. Utah Museum of Natural History Occasional Publication No. 7. Blackshaw, R. E. 1991. Control of downy brome (Bromus tectorum) in conservation fallow systems. 1991 Weed Tech. 5:557-562. Cronquist, A., A. H. Holmgren, N. H. Holmgren, J. L. Reveal, & P. K. Holmgren 1977. Intermountain flora. Vol. 6. Columbia University Press, New York, New York. FICMNEW (Federal Interagency Committee for the Management of Noxious and Exotic Weeds) 1997. Invasive plants – changing the landscape of America. Washington, D.C. Gleason, H. A., & A. Cronquist 1991. Manual of vascular plants of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York. Gray, W. E., P.C. Quinby Jr., D.E. Mathre, & J. A. Youngll 1995. Weed Tech 9:362-365. Hickman, J.C. (ed.) 1993. The Jepson manual. Higher plants of California. University of California Press, Berkeley, California. Hitchcock, A. S. 1950. Manual of the grasses of the United States. USDA, Washington, DC. Kennedy, A. C., F. L. Young, & L. F. Elliot 1989. Proceedings Western Society Weed Science 42:86. Leopold, A. 1949. A Sand County Almanac, and sketches here and there. Oxford Univ. Press, New York, New York. Mack, R. 1981. Invasion of Bromus tectorum L. into western North America; an ecological chronical. Agro-ecosystems 7:145-165. Morrow, L. A. & P. W. Stahlman 1984. The history and distribution of downy brome (Bromus tectorum) in North America. North America Weed Science 32: supplement. Muenscher, W.C. 1955. Weeds. The Macmillan Co., New York, New York. Peeper, T. F. 1984. Chemical and biological control of downy brome. North American Weed Science 32. Richardson, J. M., D. R. Gealy, & L. A. Morrow 1987. Weed Science 35: 277-281. USDA, NRCS 2000. The PLANTS database. Version: 000412. <http://plants.usda.gov>. National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Uva, R.H., J.C. Neal, & J.M. DiTomaso 1997. Weeds of the northeast. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York. 397 pp. Welsh, S. L., et al. 1987. A Utah flora. Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs No. 9. Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. Whitson, T.D. (ed.) 1991. Weeds of the west. Western Society of Weed Science, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming.