Brassica rapa L. var. campestris (L.) W.D.J. Koch

Scientific Name: Brassica rapa L. var. campestris (L.) W.D.J. Koch

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | BRRAC2 |

| Group | Dicot |

| Life Cycle | AnnualBiennial, |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herb |

| Native Locations | BRRAC2 |

Plant Guide

Description

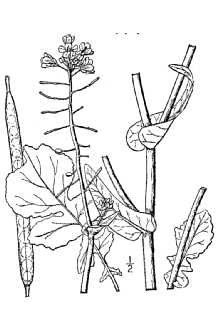

General: Field mustard is an upright winter annual or biennial that is a member of the mustard family (Brassicaceae), Plants exist as basal rosettes until flowering stems develop at maturity, usually in the second year, Plants grow 1 to 3 (or 4) ft tall from a sometimes fleshy, enlarged taproot, with a many-branched stem, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Brassica rapa L. var. campestris (L.) W.D.J. Koch., The foliage is generally hairless and sometimes covered with a whitish film, Lower leaves can reach 12 inches long, have a large central lobe, and usually one to four pairs of smaller side lobes, Upper leaves are smaller, non-lobed, and have a pointed tip and widened, clasping base, The bright yellow flowers are clustered at stem tops and have four petals that are ¼ to ½ inch long, Plants flower from January to September, depending on climate and latitude, and are insect pollinated and self-incompatible, The fruit is an elongated, two-parted capsule that splits open at the base to release the seeds at maturity, Each half of the pod has a single prominent lengthwise vein that distinguishes it from those of other Brassica species that have 3 to 7 veins, The hairless seed pods are ¾ to 4 inches long, with a narrow beak at the tip, and are born on long, ½- to 1-inch stems that point outward or upward, Seeds are about 1/16 inch wide, nearly round, and reddish-gray to black (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007; Jepson Flora Project, 2012; Pojar and MacKinnon, 1994; Taylor, 1990; Turner and Gustafson, 2006; Warwick, 2010; Whitson et al,, 2006), Distribution: This species is native to Eurasia, but has spread all over the world and is now naturalized throughout much of North America, It grows from sea level to 5,000 ft, For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site, Habitat: Field mustard grows in disturbed areas including roadsides, ditches, cultivated fields, orchards, and gardens,

Adaptation

Field mustard is an extremely adaptable plant that grows in sandy to heavy clay soils and tolerates a pH range from 4.8 to 8.5 (Hannaway and Larson, 2004). It grows best in well-drained, moist soil, but may also grow in droughty conditions, moderate heat, and soils with low fertility (Clark, 2007). Although it grows best in full sun, it will grow in moderate shade. Field mustard is hardy through USDA plant hardiness zone 7. Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Guide Photo by George W. Williams, 2011, courtesy of Wildflowers in Santa Barbara at http://sbwildflowers.wordpress.com.

Uses

Cover crop: Field mustard is used as a winter annual or rotational cover crop in vegetable and specialty crops as well as row crop production. It has the potential to prevent erosion, suppress weeds and soil-borne pests, alleviate soil compaction, and scavenge nutrients (Clark, 2007). It has rapid fall growth, high biomass production, and nutrient scavenging ability following high input cash crops. Field mustard can be grown as a cover crop alone or in a mix with other brassicas, small grains, or legumes. In the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Great Lakes bioregions, it appears to be a good tool as a biofumigant cover crop for control of nematodes, soil-borne diseases including the fungal pathogen (Rhizoctonia) responsible for damping-off, weeds, and other pests. When biomass is incorporated into the soil, soil microbes break down sulfur compounds in the plant into isothiocyanide, which can act as a fumigant and weed suppressant (Olmstead, 2006). Field mustard produces 2,000 to 5,000 pounds of dry matter per acre per year and biomass contains 40 to 160 lb/acre total N (Clark, 2007). Intercropping: Intercropping can increase cropping system diversity and profitability by producing two simultaneous crops on the same land. In New Mexico, forage turnip was interseeded between rows of chili peppers and sweet corn without affecting yields of the cash crop when the turnip seeding was timed correctly (Gulden et al., 1997a, 1997b). Forage: Cultivars with larger roots, commonly called forage turnip, have been a popular forage crop for livestock in Europe and Asia for at least 600 years (Undersander et al., 1991). Forage turnip is a useful crop for extending the fall grazing season for dairy cows and other livestock (Thomet and Kohler, 2003; UMass Extension, 2012). Forage turnip was largely replaced with corn silage in the early 1900s because it required less labor. The use of forage turnip increased again in the 1970s with the development of new cultivars that could be seeded directly into pastures. Aboveground vegetation contains 20 to 25% crude protein, 65 to 80% in vitro digestible dry matter (IVDDM), about 20% neutral detergent fiber (NDF), and about 23% acid detergent fiber (ADF). The roots contain 10 to 14% crude protein, and 80 to 85% IVDDM (Undersander et al., 1991). Caution: The roots, leaves, and especially seeds of Brassica rapa and related species contain sulfur compounds (glucosinolates) that can irritate the digestive tracts or create thyroid problems in livestock if consumed in large quantities over time (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007). Toxicity in livestock, particularly horses, can create symptoms such as colic, diarrhea, anorexia, excessive salivation, and thyroid enlargement (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007; Ahmann Hanson, 2008). Problems arise when livestock eat large quantities of seed or are confined to pastures composed primarily of mustards. Nitrate nitrogen toxicity can also be a problem for ruminants if field mustard is grazed when immature or if soil N levels are high (Undersander et al., 1991). Vegetable crop: Brassica rapa has been cultivated in Europe as a vegetable for human consumption for more than 4,000 years (Duke, 1983). Turnip roots are the product of horticultural cultivars of this species. The leaves, known as “turnip greens” or “turnip tops”, are also eaten raw or cooked and have a slightly spicy flavor similar to mustard greens. Rapini, or broccoli raab, is another vegetable derived from a cultivar of this species. Seed: Canola is a cultivar of either Brassica rapa or B. napus. Seed was developed with lower levels of erucic acid and glucosinolates to make the oil safer for human consumption (Canola Council of Canada, 2012). The name canola comes from Canadian oil, low acid; rapeseed oil must contain less than 2% erucic acid to qualify as canola. Canola and rapeseed oils are used as cooking oil, industrial lubricants, lamp oil, in soap making, biodiesel production, and the meal is used as a protein source in animal feed (Canola Council of Canada, 2012; Plants for a Future, 2012).

Ethnobotany

Field mustard roots and leaves were used as food by many Native American tribes following introduction of the plant by white settlers (Moerman, 2012). Various parts of the plant have been used as a folk remedy for different types of cancer, either by boiling the mashed stems and leaves, powdering the seeds, or making a salve from the flowers (Duke, 1983; Plants for a Future, 2012).

Status

This plant may become weedy or invasive, primarily in cultivated fields and disturbed or waste areas, and may displace desirable vegetation if not properly managed. Brassica rapa is listed as an invasive weed in Weeds of the West and Weeds of the United States and Canada (SWSS, 1998; Burrill et al., 2006). Brassica spp. are state-listed restricted noxious weed seeds in Arizona and prohibited noxious weed seeds in Michigan (MDA, 2011; Parker, 1972). Please consult with your local NRCS Field Office, Cooperative Extension Service office, state natural resource, or state agriculture department regarding its Volunteer field mustard cover crop in a California vineyard. Photo by Gerald and Buff Corsi © California Academy of Sciences. status and use. Please consult the PLANTS Web site (http://plants.usda.gov/) and your state’s Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Planting Guidelines

Drill seed in the spring, late summer, or fall at a rate of 1.5 to 10 lb/acre and a depth of ½ to ¾ inch in rows 4 to 12 inches apart; alternately, broadcast at 8 to 14 lb/acre followed by cultipacking (Clark, 2007; Hannaway and Larson, 2004; Knodel and Olson, 2002). Field mustard has approximately 150,000 to 200,000 seeds per pound, so a seeding rate of one pound per acre will result in approximately 3 to 5 seeds per square foot. The target spacing for a pure stand is 5 to 6 plants per square foot (Undersander et al., 1991). Some ecotypes have seed that requires a cold, moist period to break dormancy and stimulate germination (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007). Winter cover crops should be established as early as possible, or at least four weeks before the average date of the first hard freeze (Clark, 2007). Soil temperatures for planting should be between 45–85°F. In northern climates, spring-planted crops generally produce less aboveground biomass and root growth, and are less reliable due to cool soil temperatures.

Management

Fertilization: Soils should be tested prior to planting to determine fertilizer and lime requirements. When planted as a fall catch crop following a cash crop that has been well fertilized, additional fertilizer may not be needed (Duke, 1983). Lime should be added to correct pH to 5.5 to 6.8. Fertilizer applications, if required, should be banded at least 2 inches to the side and below the seed. Forage: Forage turnips reach their maximum yields 70 to 100 days after planting. Turnip tops can be grazed up to four times at four week intervals to a 5-inch stubble. Animals can be allowed to graze plants to ground level including the roots on the final grazing (Undersander et al., 1991). Forage crops should not be allowed to go to seed and should be fed in combination with other forages to avoid problems with toxicity (see caution note above in Uses section). Cover crop termination: Field mustard usually survives early frost, but temperatures below 25°F will likely kill stands. However, some winter-type cultivars can withstand temperatures as low as 10°F (Clark, 2007). Winterkilled mustard decomposes quickly, leaving a seedbed that is easy to plant into the following spring. If the crop does not winterkill, it can be terminated with herbicide, by flail mowing (good for no-till systems), or tillage (especially for biofumigation) before the plants have reached full flower. They can also be killed with a roller-crimper when they are in flower. Some Brassica rapa cultivars have become resistant to glyphosate treatments (Clark, 2007), so another termination method may be needed for complete kill. Cover crop termination should occur before or at full bloom to avoid seed set and volunteers in subsequent crops.

Pests and Potential Problems

Field mustard is susceptible to a number of viruses, including Arabis mosaic nepovirus, broad bean wilt fabavirus, and cauliflower mosaic caulimovirus (Hannaway and Larson, 2004). It is also susceptible to turnip mosaic virus, which is transmitted by many species of aphids. Pest problems are best avoided by planting resistant cultivars and/or using crop rotations to break disease cycles (Black, 2001). Clubroot and black rot are the most serious diseases of turnips, while turnip aphid, root maggot, and flea beetles are the most damaging insect pests (Duke, 1983). In order to avoid disease problems, Brassicas should not be grown on the same field for more than two consecutive years. A six year rotation should be used in areas with clubroot (Undersander et al., 1991). Flea beetles can also cause extensive damage in canola, and are best avoided by planting on wider row spacing (12 inches) from April to mid-May, with a no-till planter in fall, or by treating seed with a systemic insecticide (Knodel and Olson, 2002). Wild mustards, including field mustard, can also harbor pests and diseases that attack closely related crops in the mustard family (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007).

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

It has been reported that field mustard seeds can survive for fifty years or more if they are deeply buried, but seeds closer to the soil surface are not as persistent (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007). Modern cover crop cultivars do not have hard seed, but may have a small percentage of “latent seed” that fails to germinate immediately when planted if adequate growing conditions such as light and moisture are lacking (S. Davidson, AgriSeed Testing, G. Weaver, Weaver Seed, and D. Wirth, Saddle Butte Ag, personal communication, 2017). If left to mature in unmanaged areas, weedy mustards also may become a fire hazard when they dry at the end of the growing season (UC IPM, 2011).

Control

Unwanted plants can be mowed or manually removed before seeds mature to deplete the seedbank (DiTomaso and Healy, 2007). Managing stands with fire or other physical disturbance is not recommended for mustard species as this can increase populations. Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method.

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Good seed production requires cross pollination by various insects. One or two hives per acre can ensure good seed set (Duke, 1983). Seed production fields need to have proper isolation distances among varieties and all other forms of B. juncea, B. campestris, and B. napus. Minimum isolation distances are mandated at the state or province level in the US and Canada, and for Brassicas they vary from ½ to 5 miles; in England, the minimum isolation distance is 3,000 ft, while in New Zealand it is 1,300 ft. Seeds will shatter when ripe, so the crop must be harvested just before the mature stage. Canola seed yields average between 860 and 1,200 lb/acre in Canada, but can be as high as 4,000 lb/acre (Canola Council of Canada, 2012). Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Field mustard seed is generally available from commercial sources, but quantities may be limited, so it is best to check with seed suppliers a few months prior to planting. A list of cover crop seed suppliers is available at http://www.sare.org/Learning-Center/Books/Managing-Cover-Crops-Profitably-3rd-Edition/Text-Version/Appendix-C (Clark, 2007). There are a number of horticultural cultivars of turnip and rapini, some of which have been bred for disease resistance, as well as cultivars of forage turnip bred for increased dry-matter yield or other traits. ‘Green Globe’, ‘York Globe’ (New Zealand), and ‘Sirius’ turnip (Sweden) are recommended for forage use in the Upper Midwest (Undersander et al., 1991). ‘Purple Top’, ‘Forage Star’ (an aphid-tolerant variety), and ‘Green Globe’ have performed satisfactorily in Pennsylvania test plots (Penn State Extension, 2012). ‘Macro Stubble’ and ‘Kapai’ turnip had the highest dry matter yields in preliminary research farm trials in Massachusetts, while ‘Topper’ turnip had the highest fresh forage yield in a later study (UMass Extension, 2012). ‘Tyfon’, a high yielding variety that is a cross between forage turnip (B. rapa var. rapa) and Chinese cabbage (B. pekinensis), performs best under a multiharvest system. Cultivars should be selected based on the local climate, resistance to local pests, and intended use. Consult with your local land grant university, local extension or local USDA NRCS office for recommendations on adapted cultivars for use in your area.

Literature Cited

Ahmann Hanson, G. 2008. Equines & toxic plants: database of toxic plants in the United States. Univ. of Idaho, Moscow. http://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/range/toxicplants_horses/Toxic%20Plant%20Database.html (accessed 1 Aug. 2017). Black, L.L. 2001. Fact sheet: turnip mosaic virus. In: Vegetable diseases: a practical guide. AVRDC-The World Vegetable Center. www.avrdc.org/LC/cabbage/tumv.html (accessed 1 May 2012). Burrill, L.C., S.A. Dewey, D.W. Cudney, B.E. Nelson, R.D. Lee, R. Parker, and T.D. Whitson, editors. 2006. Weeds of the west, 9th edition. Western Society of Weed Science with Western CSREES and Univ. of Wyoming, Laramie. Canola Council of Canada. 2012. www.canolacouncil.org/ (accessed 2 May 2012). Clark, A., editor. 2007. Managing cover crops profitably, 3rd ed. National SARE Outreach Handbook Series Book 9. National Agricultural Laboratory, Beltsville, MD. DiTomaso, J.M., and E.A. Healy. 2007. Weeds of California and other western states. UC ANR Publ. 3488. Univ. of California, Division of Agric. and Nat. Resources, Davis. Duke, J.A. 1983. Brassica rapa L. In: Handbook of energy crops. Center for New Crops & Plant Products, Purdue Univ. www.hort.purdue.edu/ newcrop/duke_energy/Brassica_rapa.html (accessed 2 May 2012). Gulden, S.J., C.A. Martin, and D.L. Daniel. 1997a. Interseeding forage brassicas into sweet corn: forage productivity and effect on sweet corn yield. J. Sustainable Agriculture 11(2-3): 51-58. Gulden, S.J., C.A. Martin, and R.L. Steiner. 1997b. Interseeding forage brassicas into chile: forage productivity and effect on chile yield. J. Sustainable Agriculture 11(2-3):41-49. Hannaway, D.B., and C. Larson. 2004. Forage fact sheet: field mustard (Brassica rapa L. var. rapa). Oregon State Univ., Corvallis. http://forages.oregon state.edu/php/fact_sheet_print_ffor.php?SpecID=152&use=Forage (accessed 1 May 2012). Jepson Flora Project. 2012. Jepson eFlora (v. 1.0), Brassica rapa, I.A. Al-Shehbaz. http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/get_IJM.pl? tid=16081 (accessed 1 May 2012). Knodel, J.J., and D.L. Olson. 2002. Crucifer flea beetle biology and integrated pest management in canola. North Dakota State Univ. www.ag.ndsu.edu/ pubs/plantsci/pests/e1234w.htm (accessed 2 May 2012). Madson, B.A. 1951. Winter covercrops. Circular 174. Agric. Ext. Serv., College of Agric., Univ. of California, Berkeley. http://archive.org/details/ wintercovercrops174mads (accessed 1 May 2012). MDA (Michigan Department of Agriculture). 2011. Michigan summary of plant protection regulations, updated March 1, 2011. Pesticide & Plant Pest Management Division. http://nationalplantboard.org/ docs/summaries//michigan.pdf (accessed 30 Apr. 2012). Moerman, D. 2012. Brassica rapa. In: Native American Ethnobotany Database [Online]. Univ. of Michigan, Dearborn. http://herb.umd.umich.edu/herb/search.pl (accessed 1 May 2012). Olmstead, M.A. 2006. Cover crops as a floor management strategy for Pacific Northwest vineyards. EB2010. Washington State Univ. Extension, Prosser. http://cru.cahe.wsu.edu/CEPublications/eb2010/eb2020.pdf (accessed 2 May 2012). Parker, K.F. 1972. An illustrated guide to Arizona weeds. 4th edition 1990. Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson. http://www.uapress.arizona.edu/onlinebks/WEEDS/GGENERA.HTM (accessed 30 Apr. 2012). Penn State Extension. 2012. Pastures: annual forages for pastures. College of Agric. Sciences, Pennsylvania State Univ. http://extension.psu.edu/agronomy-guide/cm/sec8/sec810d (accessed 2 May 2012). Plants for a Future. 2012. Brassica rapa L. In: Plant database [online]. www.pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Brassica+rapa (accessed 2 May 2012). Pojar, J., and A. MacKinnon, editors. 1994. Plants of the Pacific Northwest coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska. BC Ministry of Forests and Lone Pine Publ., Vancouver. SAREP (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program). 2012. Mustards. In: SAREP cover crops database. Agricultural Sustainability Institute, Univ. of California, Davis. www.sarep.ucdavis.edu/database/covercrops (accessed 1 May 2012). SWSS (Southern Weed Science Society). 1998. Weeds of the United States and Canada. CD-ROM. Southern Weed Science Society, Champaign, IL. Taylor, R.J. 1990. Northwest weeds: the ugly and beautiful villains of fields, gardens, and roadsides. Mountain Press Publ. Co., Missoula, MT. Thomet, P., and S. Kohler. 2003. Extending the grazing season with turnips. Utilisation of grazed grass in temperate animal systems, 229. In: Satellite Workshop on Utilisation of Grazed Grass in Temperate Animal Systems. Wageningen Academic Publ., Wageningen, Netherlands. Turner, M., and P. Gustafson. 2006. Wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest. Timber Press, Inc., Portland, OR. UC IPM. 2011. Weed gallery: mustards. Statewide IPM Progr., Agric. and Nat. Resources, Univ. of California. www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/WEEDS/ mustards.html (accessed 1 May 2012). UMass Extension. 2012. Brassica fodder crops for fall grazing. Center for Agriculture, Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst. http://extension.umass.edu/cdle/fact-sheets/brassica-fodder-crops-fall-grazing (accessed 2 May 2012). Undersander, D.J., A.R. Kaminski, E.A. Oelke, L.H. Smith, J.D. Doll, E.E. Schulte, and E.S. Oplinger. 1991. Turnip. In: Alternative field crops manual. Wisconsin and Minnesota Cooperative Extension, Univ. of Wisconsin, Madison, and Univ. of Minnesota, St. Paul. www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/afcm/turnip.html (accessed 2 May 2012). USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British Possessions. 3 vols. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. Vol. 2:193. Warwick, S.I. 2010. Brassica rapa. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, editor, Flora of North America North of Mexico, Vol. 7 Magnoliophyta: Salicaceae to Brassicaceae. www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=200009273 (accessed 1 May 2012). Citation Young-Mathews, A. 2012. Plant guide for field mustard (Brassica rapa var. rapa). USDA-Natural Resources

Conservation

Service, Corvallis Plant Materials Center, Corvallis, OR. Published August 2012 Edited: 3May2012 plsp; 17May2012 aj; 22May2012 cs; 29Aug2012 gm; 16Aug2017 aym For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or Conservation District at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/ and visit the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov/ or the Plant Materials Program Web site: http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov. PLANTS is not responsible for the content or availability of other Web sites. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html.