Brahea serrulata (Michx.) H. Wendl.

Scientific Name: Brahea serrulata (Michx.) H. Wendl.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | BRSE3 |

| Group | Monocot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | ShrubTree, |

| Native Locations | BRSE3 |

Plant Guide

Uses

Cultural: Saw palmetto featured prominently in the material cultures of some Southeastern tribes. The Tequesta, Creek, Miccosukee, and Seminole gathered and ate the berries in late summer or fall (Bennett and Hicklin 1998; Tebeau 1968; Rusby 1906). Romans (1999:145) said in 1775 in reference to the Creek: “… they dry peaches and persimmons, chestnuts and the fruit of the chamaerops [Serenoa repens].” The young, sweet, and tender shoots are also edible (Small 1926). Naturalist William Bartram (1996:559), in his travels in the Southeastern United States in the 1770s, noted that there were “several species of palms, which furnish them [tribes] with a great variety of agreeable and nourishing food” and very likely saw palmetto was one of them. Evidence for saw palmetto use is widespread in coastal archaeological sites in southern and central Florida, being an extremely important food for Florida’s pre-Columbian peoples ( McGoun 1993 cited in Bennett and Hicklin 1998). The seeds of these fruits also are found at sites in northern Florida and in the Lower Mississippi Valley (Alexander 1984 and Kidder and Fritz 1993 cited in Scarry 2003). The Choctaw, Koasati, Miccosukee, and Seminole used and continue to use the split leaf petioles for basketry (Bennett and Hicklin 1998; Bushnell 1909; Colvin 2006; Sturtevant 1955:504). Thomas Colvin (2006:80) describes the sustainable harvest practices of the Choctaw that he learned from the Johnsons: “The best palmetto (Serrenoa serrulata) [now Serenoa repens] grows where the marsh meets the swamp or bayou. When cutting it, I always leave stalks with one or two green fronds, as well as the center growing core of the plant, as the Johnsons [Choctaw] taught me to do, so that the plant will not die. This can be done twice each year. Palmetto baskets are made from the cortical layer of the stalks, not from the fronds.” The Choctaw remove the rigid teeth from the petioles and split the stalks into five or six straws, peeled and trimmed them to the proper width, and dried them in the sun. They might be then dyed black, red, or yellow. Sifters, pack, heart, and elbow baskets all carry its leaves. The Seminole pounded corn into a powder, sifted it through woven palmetto fibers, and then placed it in a kettle of boiling water to make a porridge called sofkee (Covington 1993). Figure 2. Houma Indians on the Lower Bayou Lafourche, Louisiana standing in from of a house thatched with either saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) or dwarf palmetto (Sabal minor). Courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution. Photo taken in 1907. The Seminole used the leaves for bedding in a temporary camp. The Chitimacha, Choctaw, Houma, Miccosukee, and Seminole thatched their houses with either saw palmetto leaves or the leaves of Sabal minor or Sabal palmetto. (Bushnell 1909; Campisi 2004; Sweeny 1936; Bennett and Hicklin 1998). The Miccosukee and Seminole made and continue to make dance fans and rattles used in ceremonies and toy dolls for children out of saw palmetto (Bennett and Hicklin 1998; Sturtevant 1955). Figure 3. Seminole doll made from saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) leaf sheath fibers, Immokalee, FL. Oct. 1997. Photo by B.C. Bennett. The plant provided punk for lighting fires and the broad leaves made a kind of fire fan for fanning fires (Sturtevant 1955). Seminole fish drags, rope, and brushes were made out of the palm fibers from leaf sheaths, stems, and roots (Sturtevant 1955:504). In early Materia Medicas, the berries were used by non- Indians to treat all diseases of the reproductive glands, as an aid to digestion, and to combat colds and chronic bronchitis of lung asthma (Hutchens 1973). Today saw palmetto is used to promote urination, reduce inflammation and for treatment of prostate disorders such as prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), an enlarged prostate gland condition common in older men (Sosnowska and Balslev 2009). Harvesting of fruits from pinelands has heightened in the last fifteen years and saw palmetto supplements are widely available in health food stores (Carrington and Mullahey 2006). Although uncommon, complications from the use of saw palmetto include intraoperative hemorrhage, gastrointestinal complaints, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as additive anticoagulant effects and prolong bleeding time (Integrative Medicine Service of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center 2008). Non-Indian settlers split saw palmetto leaves into shreds and boiled them and dried them in the sun one or two days and made them into durable mattresses and pillows. The leaves were also collected, dried, put up in bales and sold for paper stock in the late 1800s and the strong roots were made into scrubbing brushes (Hale 1898). African- Americans made palmetto hats for Southern soldiers (Porcher 1991). Saw palmetto is often viewed as an impediment to cattle grazing and farming (Carrington and Mullahey 2006), but there are some exceptions. It is an important component in the winter diet of cattle in south Florida rangelands and sheep grazing has been used in Florida to control saw palmetto (Kalmbacher et al. 1984; Marshall et al. 2008). One study that evaluated saw palmetto for biomass potential found that the low biomass yields and high concentrations of extractives and lignin indicate that saw palmetto does not have the desired characteristics for biomass energy conversion (Pitman 1992). Saw palmetto can be planted for watershed protection, erosion control, and phosphate-mine reclamation (Callahan et al. 1990 cited in Van Deelen 1991). Wildlife: Ecologically, saw palmetto is labeled a “keystone species” in southeastern, and particularly Florida ecosystems (Carrington and Mullahey 2006). Over 100 animal species use saw palmetto for nesting, foraging, or for cover (Maehr and Layne 1996). Both the threatened Florida panther (Felis concolor ssp. coryi) and the threatened Florida black bear (Ursus americanus ssp. floridanus) use colonies of saw palmetto as cover. Black bears have their young in the protective cover of dense plants (Bennett and Hicklin 1998). Florida burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia floridana) excavate burrows in saw palmetto patches (Mrykalo et al. 2007). Located in the dry prairies of southern Florida with scattered palmettos, are two declining grassland birds, the grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum pratensis) and the sedge wren (Cistothorus platensis), that overwinter there (Butler et al. 2009). Bachman’s sparrows (Aimophila aestivalis) use saw palmetto clumps as shelter to escape from predators (Dean and Vickery 2003). Beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus) use clumps of palmetto as cover (Extine and Stout 1987). Cotton mice (Peromyscus gossypinus) and golden mice (Ochrotomys nuttalli) build spherical nests of saw palmetto fibers (Frank and Layne 1992). Saw palmetto flowers attract several hundred species of pollinators (Carrington et al. 2003). In 1898, Hale (1898:8) commented on the “great fattening properties of the berries” for wildlife. Saw palmetto fruits are high in crude fiber, potassium, ash, fats, and sodium and serve as an energy-rich food for raccoons (Procyon lotor), gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), rats, gopher tortoises (Gopherus poloyphemus), opossums (Didelphis marsupialis), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), bobwhite quail (Colinus virginianus), black bears (Ursus americanus), feral hogs, and various birds such as American robins (Turdus migratorius), northern mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos), yellow-rumped warblers (Dendroica coronata) and pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus) (Abrahamson and Abrahamson 1989; Hale 1898; Maehr and Layne 1996; Martin et al. 1951). Fish and waterfowl also consume the fleshy fruits (Hale 1898). In Florida, saw palmetto berries are the single most important food to black bears (Maehr 2001). In Okefenokee, for example, black gum (Nyssa sylvatica) and saw palmetto fruits were the most important foods for the Florida black bears based on scat analysis. These are such important foods, they govern bear population dynamics (cub production) (Dobey et al. 2005). Florida box turtles (Terrapene carolina bauri) also feed on their fruits and passage of the seeds through the turtles’ digestive tracts greatly enhances their germination percentage and germination rate (Liu et al. 2004). Wasps (Mischocyttarus mexicanus cubicola) nest on the underside of horizontally-oriented leaves of saw palmetto in Florida (Hermann et al. 1985). Red widow spiders (Latrodectus bishopi) in Florida scrub build silken retreats in saw palmetto leaves (Carrel 2001). Mortality of saw palmetto on restoration sites can be due to animal rooting of the forming rhizome by feral pigs (Sus scrofa) (Schmalzer et al. 2002).

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Description

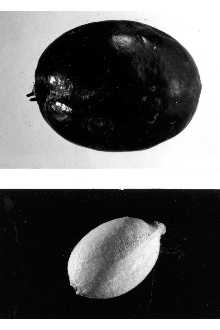

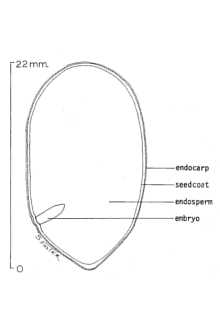

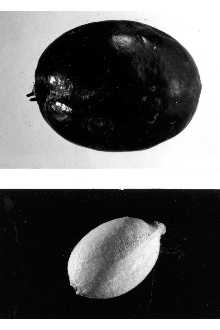

General: Palm family (Arecaceae). Saw palmetto is a low shrubby palm with a creeping, horizontal, simple or branched stem. Long-lived, some of the larger palms are centuries old (Abrahamson 1995). The leaves are fan- shaped, up to one meter across, and are divided into 18-30 segments (Radford et al. 1968; Hale 1898). They have petioles up to 1.5 m in length nearly always with sharp, rigid recurved teeth (Radford et al. 1968). Fertile ramets produce between one and five inflorescences with small, cream-colored and fragrant flowers that have three petals and six stamens. The edible fruit is a drupe, bluish to black when ripe between August and October, and resembling black olives in size and shape (Zona 2000; Bombardelli and Morazzoni 1997; Hutchens 1973; Bennett and Hicklin 1998). Like all palms, saw palmetto has roots that are mycorrhizal, enabling it to grow on nutrient poor native soil (Fisher and Jayachandran 1999). Distribution: This palm occurs in Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida (Zona 2000). Both William Bartram and Edwin Hale wrote about the palmetto scrubs extending unbroken for miles in the Southeastern United States (Bartram 1996; Hale 1898). For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: The plant is the most common palm in the United States and grows in a wide variety of habitats including flatwoods, prairies, scrub, mesic hammocks, maritime forests, short-hydroperiod swamps and sandy dunes (Bennett and Hicklin 1998; Zona 2000). Saw palmetto occurs on a range of sites from xeric to hydric and a diversity of soils from strongly acidic to alkaline (McNab and Edwards, Jr. 1980). It is often the dominant shrub in the understory of Pinus elliottii, P. serotina, and P. palustris flatwoods (Bennett and Hicklin 1998; Monk 1965). Many of these plant communities have evolved with frequent lightning and Indian-set fires. For example, upland Florida shrublands dominated by clonal oaks intermixed with palmettos and other shrubs have evolved with fire (Myers 1990; Schmalzer and Hinkle 1992). In the absence of fire, it is disappearing as slow structural changes in the vegetation result in diffuse ecotones and less habitat heterogeneity (Boughton et al. 2006). Fire return intervals in coastal plain savannas are every two to eight years, and one to 10 years in xeric sand hills (Christensen 1981 and Glitzenstein et al. 1995 cited in Wagner 2003). Flatwoods are dominated by saw palmetto and slash pines (Pinus elliottii) and typically burn every 2-9 years (Schafer and Mack 2010). In certain plant communities, such as the dry prairies of Southern Florida, the absence of frequent fire can favor the domination of saw palmetto. Without fire every one to three years, saw palmettos exclude other grass and forb species and dominate the landscape (Butler et al. 2009). Figure 4. American Indians in the Southeast, burning the understory of a pine stand. Saw palmetto is often an understory associate with long leaf pine and native grasses. Courtesy of the Longleaf Alliance, 2012. Southeastern Indians set fires in the woods and prairies to foster the growth of important food plants, keep areas open to increase visibility and movement, drive game, increase palatability, accessibility, and nutrition of forage plants for ungulates, clear areas for farming, and other purposes (Stewart 2002). Several of the habitats where saw palmetto is found, Florida scrub, longleaf pine forests, loblolly-shortleaf pine hardwood forests, and prairies are rare and declining due to conversion to agriculture, development, and the absence or prevention of fire (Noss et al. 1995; Schmalzer et al. 2002). Agriculture, both Native American and Euro- American, resulting in cleared fields, may have kept areas relatively free of saw palmetto on Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia (Bratton and Miller 1994).

Adaptation

Studies show saw palmetto not only thrives in a fire-prone environment, but is also activated reproductively by fire, Saw palmetto has waxy, evergreen leaves that are quite flammable, After fire, the plant resprouts from root crowns and rhizomes and grows rapidly (Abrahamson 1984; 1999; Van Deelen 1991; Schmalzer and Hinkle 1992), Winter-burned stands recover faster than summer- burned stands (Abrahamson 1984), Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Brahea serrulata (Michx.) H. Wendl.., However, seedlings grow slowly, especially on nutrient-poor soils, and they have a limited ability to recolonize former habitats (Abrahamson 1995),

Establishment

Ripe fruit can be gathered by hand-picking or cutting the fruit-bearing panicle (Van Deelen 1991). Saw palmetto seeds have low and slow germination rates. In one trial, soaked or imbibed seeds held for one week at 35 degrees C provided the highest germination when seeds were subsequently planted in sterile quartz media kept at 30 degrees C in a greenhouse (Carpenter 1987). D.J. Makus (2008) found that germination of saw palmetto seeds can be heightened by removal of any fleshy material around the seeds, washing the seeds, and soaking them in water for 24 hours before sowing them in a germination medium. Outplanting the seeds in a lighter textured soil resulted in improved plant height by 20 percent and a two-fold increase in fruit yield by the sixth year (Makus 2008).

Management

Because flowering is connected to fire, saw palmetto stands under conservation protection need to be prescription burned to maintain population viabilities (Abrahamson 1999). Fire not only induces flowering in appropriately sized individuals, it also influences whether that stimulus will result in inflorescences via overstory canopy reduction and enhancement of available light (Abrahamson 1999). Burning saw palmetto understories every 3 to 5 years, will maintain fruit production for white-tailed deer (Fults 1991 cited in Van Deelen 1991). Additionally, controlled harvesting of the berries for modern medicine will leave fruits for wildlife populations that also depend on nutrient-rich palmetto fruits (Abrahamson 1999). Managing areas with fire to include both longer and shorter fire intervals will create a diverse landscape mosaic, taking into account old palmetto stands that bears and panthers use as cover for dens (Conway Duever 2011). Figure 5. Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) fruits drying at Plantation Botanicals, Felda, FL. Sept. 1996 Photo by B .C. Bennett.

Control

Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warrant the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective. Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Commercial sources of saw palmetto seeds are frequently available (Van Deelen 1991). This plant is available from native plant nurseries and is widely planted as an ornamental (Bennett and Hicklin 1998). It grows slowly though and doesn’t transplant easily (Bennett and Hicklin 1998; Abrahamson 1995). Also check with your local NRCS Plant Materials Center for possible sources of existing plant materials.

References

Abrahamson, W.G. 1984. Species responses to fire on the Florida Lake Wales Ridge. Amer. J. Bot. 71(1):3543. _______________1995. Habitat distribution and competitive neighborhoods of two Florida palmettos. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122:1-14. _______________1999. Episodic reproduction in two fire-prone palms, Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia (Palmae). Ecology 80:100-115. Abrahamson, W.G. and C.R. Abrahamson. 1989. Nutritional quality of animal dispersed fruits in Florida sandridge habitats. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 116(3):215-228. _______________2009. Life in the slow lane: palmetto Florida’s nutrient-poor uplands. Castanea 74(2):123-132. Alexander, M.M. 1984. Paleoethnobotany of the Fort Walton Indians: High Ridge, Velda, and Lake Jackson Sites. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, Florida State University, Tallahassee. Bartram, W. 1996. William Bartram Travels and Other Writings. Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y. Bennett, B.C. and J.R. Hicklin. 1998. Uses of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens, Arecaceae) in Florida. Economic Botany 52(4):381-393. Bombardelli, E. and P. Morazzoni. 1997. Serenoa repens (Bartram) J.K. Small. Fitoterapia. Vol. LXVIII(2):99-113. Boughton, E.A., P.F. Quintana-Ascencio, E.S. Menges, and R.K. Boughton. 2006. Association of ecotones with relative elevation and fire in an upland Florida landscape. Journal of Vegetation Science 17(3):361-368. Bratton, S.P. and S.G. Miller 1994. Historic field systems and the structure of maritime oak forests, Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 121:(1)1- 12. Bushnell, D.I., Jr. 1909. The Choctaw of Bayou Lacomb. St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, Number 48. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Callahan, J.L., C. Barnett, and J.W.H. Cates 1990. Palmetto prairie creation on phosphate-mined lands in central Florida. Restoration and Management Notes 8(2):94-95. Campisi, J. 2004. Houma. Pages 632-641 in: Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 14, and Southeast. R.D. Fogelson (ed.). Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Carrel, J.E. 2001. Population dynamics of the red widow spider (Araneae: Theridiidae). The Florida Entomologist 84(3):385-390. Carrington, M.E. and J.J. Mullahey. 2006. Effects of burning season and frequency on saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) flowering and fruiting. Forest Ecology and Management 230:69-78. Carrington, M.E., T.D. Gottfried, and J.J. Mullahey. 2003. Pollination biology of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens: Palmae) in southwest Florida. Palms 47(2):95-103. Christensen, N.L. 1981. Fire regimes in Southeastern ecosystems. Pages 112-136 in: Fire Regimes and Ecosystem Properties. H.A. Monney, N.L. Christensen, J.E. Lotan, and W.E. Reiners. General Technical Report WO-26. U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Washington, D.C. Colvin, T.A. 2006. Cane and palmetto basketry of the Choctaw of St. Tammany Parish. Pages 73-95 in: The Work of Tribal Hands: Southeastern Indian Split Cane Basketry. D.B. Lee and H.F. Gregory (eds.). Northwestern State University Press, Natchitoches, Louisiana. Conway Duever, L. 2011. Ecology and Management of Saw Palmetto. A report submitted to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Gainesville, Florida. Covington, J.W. 1993. The Seminoles of Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Dean, T.F. and P.D. Vickery. 2003. Bachman’s sparrows use burrows and palmetto clumps as escape refugia from predators. Journal of Field Ornithology 74(1):26-30. Dobey, S., D.V. Masters, B.K. Scheick, J.D. Clark, M.R. Pelton, and M.E. Sunquist. 2005. Ecology of Florida black bears in the Okefenokee-Osceola ecosystem. Wildlife Monographs 158:1-41. Extine, D.D. and I. Jack Stout. 1987. Dispersion and habitat occupancy of the beach mouse, Peromyscus polionotus niveiventris. Journal of Mammalogy 68(2):297-304. Fisher, J.B. and K. Jayachandran. 1999. Root structure and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of the palm Serenoa repens under field conditions. Plant and Soil 217:229-241. Frank, P.A. and J.N. Layne. 1992. Nests and daytime refugia of cotton mice (Peromyscus gossypinus) and golden mice (Ochrotomys nuttalli) in South- central Florida. American Midland Naturalist 127(1):21-30. Fults, G.A. 1991. Florida ranchers manage for deer. Rangelands 13(1):28-30. Glitzenstein, J.S., W.J. Platt, and D.R. Streng. 1995. Effects of fire regime and habitat on tree dynamics in North Florida longleaf pine savannas. Ecological Monographs 65(4):441- 476. Hale, E.M. 1898. Saw Palmetto: Its History, Botany, Chemistry, Pharmacology, Provings, Clinical Experience and Therapeutic Applications. Boericke & Tafel, Philadelphia. Hermann, H.R., J.M. Gonzalez, and B.S. Hermann. 1985. Mischocyttarus mexicanus cubicola (Hymenopters), distribution and nesting plants. The Florida Entomologist 68(4):609-614. Hutchens, A.R. 1973. Indian Herbalogy of North America. Merco, Ontario, Canada. Integrative Medicine Service of Memorial Sloan- Kettering Cancer Center 2008. Serenoa repens (Saw Palmetto). Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology 6(1):41-42. Adapted from “AboutHerbs” database, available at www.mskcc.org/aboutherbs. Kalmbacher, R.S., K.R. Long, M.K. Johnson, and F.G. Martin. 1984. Botanical composition of diets of cattle grazing south Florida rangeland. Journal of Range Management 37(4):334-340.

Wildlife

Conservation Commission, Tallahassee. Maehr, D.S. and J.N. Layne. 1996. Florida’s all-purpose plant the saw palmetto. Palmetto (Fall) 6-10:15, 21. Makus, D.J. 2008. Seed germination methods and establishment of saw-palmetto, Serenoa repens, in South Texas. Proc. IVth IS on Seed, Transplant and Stand Establishment of Hort. Crops. D.I. Leskovar (ed.). Acta Hort. 782, ISHS. Marshall, D.J., M. Wimberly, P. Bettinger, and J. Stanturf. 2008. Synthesis of Knowledge of Hazardous Fuels Management in Loblolly Pine Forests. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Research Station

General

Technical Report SRS-110. Ashville, NC. Martin, A.C., H.S. Zim, and A.L. Nelson. 1951. American Wildlife & Plants: A Guide to Wildlife

Food

Habits. Dover Publications, Inc. New York, N.Y. McGoun, W.E. 1993. Prehistoric peoples of south Florida. The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL. McNab, W.H. and M. B. Edwards, Jr. 1980. Climatic factors related to the range of saw-palmetto (Serenoa repens (Bartr.)Small). American Midland Naturalist 103(1):204-208. Monk, C.D. 1965. Southern mixed hardwood forest of northcentral Florida. Ecological Monographs 35(4):335-354. Mrykalo, R.J., M.M. Grigione, and R.J. Sarno. 2007. Home range and dispersal of juvenile Florida burrowing owls. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119(2):275-279. Myers, R.L. 1990. Scrub and high pine. Pages 150-193 in: R.L. Myers and J.J. Ewell (eds.). Ecosystems of Florida. University of Central Florida Press, Orlando. Noss, R.F., E.T. LaRoe III, and J.M. Scott. 1995. Endangered Ecosystems of the United States: A Preliminary Assessment of Loss and Degradation. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. Pitman, W.D. 1993. Evaluation of saw palmetto for biomass potential. Bioresource Technology 43:103-106. Porcher, F.P. 1991. Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests: Medical, Economical, and Agricultural. Norman Publishing, San Francisco. Originally published in 1863 by Steam-power Press of Evans & Cogswell, Charleston, South Carolina. Romans, B. 1999. A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida. K.E. Holland Braund (ed.). The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa. Rusby, H.B. 1906. Wild Foods of the United States in September. Country Life in America 10:533- 566. Scarry, C.M. 2003. Patterns of wild plant utilization in the prehistoric eastern woodlands. Pages 50 to 104 in: People and Plants in Ancient Eastern North America. P.E. Minnis (ed.). Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C. Schafer, J.L. and M.C. Mack. 2010. Short-term effects of fire on soil and plant nutrients in palmetto flatwoods. Plant Soil 334:433-447. Schmalzer, P.A. and C.R. Hinkle. 1992. Recovery of oak- saw palmetto scrub after fire. Castanea 57(3):158-173. Schmalzer, P.A., S.R. Turek, T.E. Foster, C.A. Dunlevy, and F.W. Adrian. 2002. Reestablishing Florida scrub in a former agricultural site: survival and growth of planted species and changes in community composition. Castanea 67(2):146- 160. Small, J.K. 1926. The saw palmetto Serenoa repens. Journal of the New York Botanical Garden 27(321):193-202. Sosnowska, J. and H. Balslev 2009. American palm ethnomedicine: a meta-analysis. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 5(43):1-11. Stewart, O.C. 2002. Forgotten Fires: Native Americans and the Transient Wilderness. H.T. Lewis and M. K. Anderson (eds.). University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Sturtevant, W.C. 1955. The Mikasuki Seminole: Medical Beliefs and Practices. Ph.D. Thesis, Yale University. New Haven, Connecticut. Swanton, J.R. 1922. Early history of the Creek Indians and their neighbors. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73. Governement Printing Office, Washington, D.C. Sweeney, M.J. 1936. The Chitamacha Indians. Louisiana Works Progress Administration. Louisiana Digital Library. Tebeau, C.W. 1968. Man in the Everglades: 2000 Years of Human History in the Everglades National Park. University of Miami Press. Coral Gables, Florida. Van Deelen, T.R. 1991. Serenoa repens. In:

Fire Effects

Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ . Wagner, G.E. 2003. Eastern woodlands anthropogenic ecology. Pages 126-171 in: People and Plants in Ancient Eastern North America. P.E. Minnis (ed.). Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mark Garland for excellent editing of this Plant Guide. Iti Fabvssa provided information on Choctaw houses. Information and photographs provided by Bradley C. Bennett. Appreciation is expressed to the Shields Library at UC Davis for use of its vast library collections and interlibrary loan services to find limited and obscure library materials in book, report, and microfilm form from many institutions across the country. Non- Discrimination Statement The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers. If you believe you experienced discrimination when obtaining services from USDA, participating in a USDA program, or participating in a program that receives financial assistance from USDA, you may file a complaint with USDA. Information about how to file a discrimination complaint is available from the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights. USDA prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex (including gender identity and expression), marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, political beliefs, genetic information, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.)To file a complaint of discrimination, complete, sign and mail a program discrimination complaint form, available at any USDA office location or online at www.ascr.usda.gov, or write to: USDA Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 Or call toll free at (866) 632-9992 (voice) to obtain additional information, the appropriate office or to request documents. Individuals who are deaf, hard of hearing or have speech disabilities may contact USDA through the Federal Relay service at (800) 877-8339 or (800) 845- 6136 (in Spanish). USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). Published: December 2012 Edited: November 30 , 2012 M.K. A. and T.W.O. For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | 7 |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | High |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | None |

| Cold Stratification Required | No |

| Drought Tolerance | High |

| Fertility Requirement | Low |

| Fire Tolerance | High |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 180 |

| Hedge Tolerance | None |

| Moisture Use | High |

| pH, Maximum | 7.5 |

| pH, Minimum | 4.5 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Maxim | 100 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Minim | 50 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 80 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 35 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 18 |

| Salinity Tolerance | None |

| Shade Tolerance | Tolerant |

Morphology/Physiology

| Bloat | None |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | None |

| Resprout Ability | Yes |

| Shape and Orientation | Erect |

| Active Growth Period | Spring and Summer |

| C:N Ratio | High |

| Coppice Potential | No |

| Fall Conspicuous | No |

| Fire Resistant | No |

| Flower Color | White |

| Flower Conspicuous | No |

| Foliage Color | Yellow-Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Dense |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Dense |

| Foliage Texture | Coarse |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | No |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Lifespan | Long |

| Leaf Retention | Yes |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Height, Mature (feet) | 7.0 |

| Height at 20 Years, Maximum (fee | 10 |

| Growth Rate | Slow |

| Growth Form | Bunch |

| Fruit/Seed Color | Black |

Reproduction

| Small Grain | No |

|---|---|

| Seedling Vigor | Low |

| Seed Spread Rate | Moderate |

| Fruit/Seed Period Begin | Summer |

| Seed per Pound | 2000 |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | No |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Seed | Yes |

| Propagated by Cuttings | No |

| Propagated by Container | Yes |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | Yes |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | No |

| Fruit/Seed Period End | Fall |

| Fruit/Seed Abundance | Low |

| Commercial Availability | Routinely Available |

| Bloom Period | Late Spring |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | No |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | No |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | Yes |

| Palatable Graze Animal | Low |

| Palatable Browse Animal | Low |

| Nursery Stock Product | Yes |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | No |

| Fodder Product | No |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | Yes |