Whitebark Pine

Scientific Name: Pinus albicaulis Engelm.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | PIAL |

| Group | Gymnosperm |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Tree |

| Native Locations | PIAL |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

None

Status

In 2011 the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service announced that listing whitebark pine as threatened or endangered is warranted. However, higher priority actions precluded immediate listing. Whitebark pine has been added to the candidate species list (USDI-FWS, 2011). Populations appear to be in decline throughout the species’ range of adaptation (Keane and others 2010). White pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola), an introduced fungal pathogen, and mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) are the greatest threats to this species. Infections continue to kill trees and reduce seed sources for reproduction. Climate change is also considered a threat to whitebark pine. Species not normally adapted to alpine areas at or near timberline are likely to spread to higher elevations with increases in temperatures. In Canada, the species is predicted to decline by 57% by 2100 (COSEWIC, 2010). Fire suppression, resulting in fuel buildup over many years followed by high intensity wildfires is a major cause of mortality (USDI-FWS, 2011). Additionally, fire suppression has led to a shift in plant communities and a reduction in open habitat for whitebark pine germination. Sites previously subject to relatively frequent fires have become dominated by shade tolerant species, excluding whitebark pine. Consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Uses

Whitebark pine increases biodiversity in alpine communities by performing several important roles in the alpine ecosystems. As a pioneer species whitebark pines stabilize loose soils after disturbance. The trees capture snow drifts and create shade which slows snowmelt. Numerous Native American tribes used the seed as a food source (Moerman, 1998). Whitebark pine seeds are eaten by Clark’s nutcrackers (Nucifraga columbiana) and other birds and mammals. Grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) females, in the Yellowstone ecosystem utilize the energy-rich seed of whitebark pine to increase their fat reserves prior to hibernation. The seeds are comprised of 21% carbohydrates, 21% protein, and 52% fat, which is significantly more fat than most other bear food sources. Female bears consume more whitebark pine seeds than males, and female grizzly bears that frequently made use of whitebark pine seeds reproduced at an earlier age and exhibited higher reproductive rates than females who consumed few pine seeds. The bears obtain seed by raiding red squirrel middens (Mattson and others, 1991). Clark’s nutcracker. Photo from USDA-FS.

Description

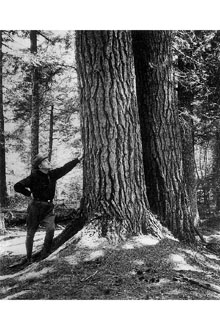

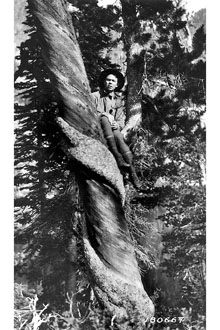

General: Pine family (Pinaceae). Whitebark pine is a medium to tall tree with a rounded or irregularly spreading canopy. Mature trees reach 5 to 20 m (16 to 66 ft). Whitebark pine trees are very long-lived. The oldest known specimen, over 1,200 years old, lives in the Sawtooth National Forest in Idaho (Perkins and Swetnam, 1996). In open areas the trees tend to be multi-stemmed and spreading, while in dense growth they are single-stemmed and upright. Above timberline they take on a krummholz (stunted, shrub-like) form. Whitebark pine has 5 needles per cluster (fascicle), 4 to 8 cm (1.5 to 3 in) long. Mature bark is whitish gray, while twigs are yellowish and pubescent. Whitebark pine trees are monoecious, bearing both male and female cones on the same plant. Female cones are dark brown to purplish, 5 to 8 cm (2 to 3 in) long (Davis, 1952). The seeds are 10 to 12 mm (0.4 to 0.5 in) long. The cones are indehiscent; seeds are not dislodged by wind. The seeds are spread almost solely by Clark’s nutcrackers, which rip the cones apart, eating some and caching the rest. Distribution: Whitebark pine trees are found on cold wind-swept ridges and peaks in western North America. Many stands are geographically isolated. Populations occur from the coastal mountain ranges of British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, south to the Sierra Range of California and east to the Rocky Mountains of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and Alberta with scattered populations in the Great Basin. For current distribution, consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Whitebark pine is adapted to steep slopes and windy exposures in subalpine and alpine habitats. It is often an early to mid-seral species. It grows with other cold and wind tolerant alpine trees such as lodgepole pine (P. contorta), Englemann spruce (Picea engelmannii), and subaplpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa). Distribution of whitebark pine. Image from the PLANTS Database. USDA-NRCS, 2011.

Adaptation

Whitebark pine is adapted to cold, windy, snowy peaks with cool summer conditions, Whitebark pine tolerates poor soil conditions of weakly developed glacial soils, Precipitation requirements are broad, Populations are found in areas receiving 50 to 250 cm (20 to 100 in) of annual precipitation (USDI-FWS, 2011), , Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Whitebark Pine.

Establishment

Whitebark pine seeds are distributed almost exclusively by Clark’s nutcrackers (Tomback and Linhart, 1990). The seeds may be carried several miles from the parent tree where the seeds are placed in caches for later consumption. Seed not eaten is available for germination under favorable conditions. Germination often occurs 2 or more years after caching. Low germination rates are related to the development and condition of the embryo and to seed coat factors (McCAughy and Schmidt, 1990). Seeds from three Canadian sources germinated poorly, despite a variety of seed coat scarification techniques with and without cold stratification (Pitel and Wang, 1980). The best results were obtained when a small cut was made in the heavy seed coat and the seed was placed adjacent to germination paper to facilitate water uptake. The seed coat is evidently a major cause of delayed regeneration or seed dormancy. Another factor explaining the low germination was the low proportion of seeds with fully developed embryos. In another test, using seed collected from Idaho, 61 percent of the seed germinated after clipping of the seed coat. Stratification for 60 days plus clipping resulted in 91 percent germination. Cold stratification for at least 150 days followed by cracking of the seed coat has been fairly successful, resulting in 34 percent germination (Hoff, 1980). In areas with long-lasting snow cover , whitebark pine trees reproduce by asexual layering. Snow bends low flexible branches into the soil. The resulting stand is a patch of krummholz trees.

Management

Physical management (pruning) of whitepine blister rust infected trees has proven labor intensive and ineffective. Efforts are being made to develop whitebark pine trees with inherited resistance to white pine blister rust. Chemical control options for mountain pine beetle are limited. At present, there are no labeled pesticides for use on mountain pine beetle Due to high elevations and remote locations, seeding, planting and restoration efforts are challenging.

Pests and Potential Problems

White pine blister rust and mountain pine beetle have significantly decreased stands and populations of whitebark pine. Mountain pine beetles are native to western North America and are a natural component in forest disturbance; however occasionally the beetles reach epidemic levels causing widespread mortality of pine trees. White pine blister rust is an introduced fungal agent (Cronartium ribicola). This rust has affected all of the western 5-needle pines causing high rates of mortality. In areas of northwestern U.S. and southwestern Canada, white pine mortality caused by blister rust and mountain pine beetle exceeds 50%. Problems relating to white pine blister rust are exacerbated as climates become warmer in higher elevations due to climate change. The combination of these factors (fire suppression, white pine blister rust, climate change, and epidemic levels of mountain pine beetles) cause federal listing as threatened or endangered to be warranted (USDI-FWS, 2011). Several other pathogens are known to infect whitebark pine; however these are not seen as major concerns. Stem infections, cankers, wood rots, molds and dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium spp.) have been identified on whitebark pine.

References

COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC assessment on the status of whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 54p. Davis, R.J. 1952. Flora of Idaho. Brigham Young University Press. Provo, Utah. 835p. Hoff, R. J. 1980. Unpublished data on file at: USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and

Range

Experiment Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Moscow, ID. Keane, R.E., Parsons, R.A. 2010. Management guide to ecosystem restoration treatments: Whitebark pine forests of the northern Rocky Mountains, USA. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-232. Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 133p. Mattson, D. J.; Blanchard, B. M.; Knight, R. R. 1991. Food habits of Yellowstone grizzly bears, 1977-1987. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 9:1619-1629. McCaughey, W., and W. Schmidt. 1990. Autecology of whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis Engelm.). In: Proceedings-Whitebark pine Ecosystems: ecology and management of a high-mountain resource. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT; 1989 March 29-31. Gen. Tech. Rep. Ogden, UT: USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. Moerman, D.E. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press. 927 p. Perkins, D.L. and T.W. Swetnam. 1996. A dendroecological assessment of whitebark pine in the Sawtooth-Salmon River region, Idaho. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 26: 2123-2133. Pitel, J. A., and B. S. P. Wang. 1980. A preliminary study of dormancy in Pinus albicaulis seeds. Canadian Forestry Service, Bi-monthly Research Notes. Jan-Feb: 4-5. Tomback, D.F., and Y.B. Linhart. 1990. The evolution of bird-dispersed pines. Evolutionary Ecology 4: 185-219. [USDA NRCS] USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2011. The PLANTS Database. URL: http://plants.usda.gov (accessed Nov. 28, 2011). Baton Rouge (LA): National Plant Data Center. USDI-Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; 12-month finding on a petition to list Pinus albicaulis as endangered or threatened with critical habitat. In: Federal Register. 76(138): 42631-42654.

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | -58 |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | No |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | None |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | Low |

| Cold Stratification Required | Yes |

| Drought Tolerance | High |

| Fertility Requirement | Low |

| Fire Tolerance | None |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 90 |

| Hedge Tolerance | None |

| Moisture Use | Medium |

| pH, Maximum | 8.0 |

| pH, Minimum | 4.8 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Maxim | 430 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Minim | 300 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 72 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 18 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 16 |

| Salinity Tolerance | None |

| Shade Tolerance | Intermediate |

Morphology/Physiology

| Bloat | None |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | None |

| Resprout Ability | No |

| Shape and Orientation | Erect |

| Active Growth Period | Summer |

| C:N Ratio | High |

| Coppice Potential | No |

| Fall Conspicuous | No |

| Fire Resistant | No |

| Flower Color | Yellow |

| Flower Conspicuous | No |

| Foliage Color | Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Moderate |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Moderate |

| Foliage Texture | Medium |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | No |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Lifespan | Long |

| Leaf Retention | Yes |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Height, Mature (feet) | 65.0 |

| Height at 20 Years, Maximum (fee | 15 |

| Growth Rate | Slow |

| Growth Form | Single Stem |

| Fruit/Seed Color | Brown |

Reproduction

| Vegetative Spread Rate | None |

|---|---|

| Small Grain | No |

| Seedling Vigor | Low |

| Seed Spread Rate | Slow |

| Fruit/Seed Period End | Fall |

| Seed per Pound | 3600 |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | No |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Seed | Yes |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

| Propagated by Container | Yes |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | Yes |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | Yes |

| Fruit/Seed Period Begin | Summer |

| Fruit/Seed Abundance | Low |

| Commercial Availability | Contracting Only |

| Bloom Period | Mid Summer |

| Propagated by Cuttings | No |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | No |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | No |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | No |

| Palatable Browse Animal | Low |

| Nursery Stock Product | No |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | No |

| Fuelwood Product | Medium |

| Fodder Product | No |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | No |