Live Oak

Scientific Name: Quercus virginiana Mill.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | QUVI |

| Group | Dicot |

| Life Cycle | Perennial |

| Growth Habits | Tree |

| Native Locations | QUVI |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

southern live oak, southeastern live oak, Virginia live oak

Description

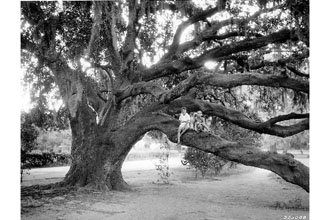

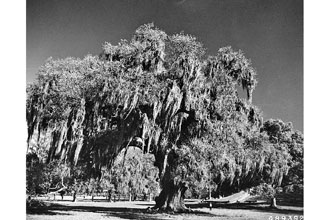

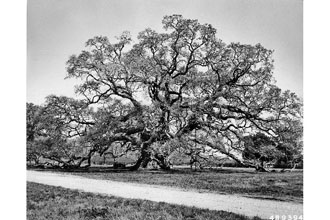

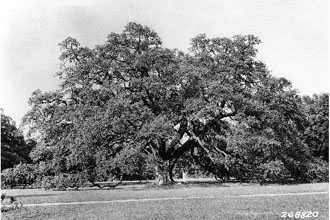

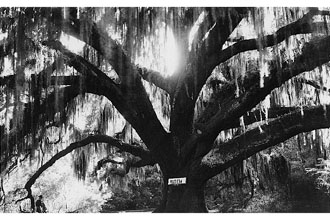

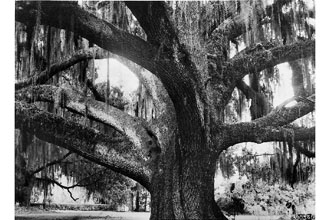

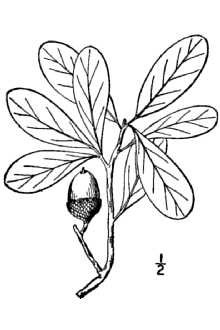

General: Medium to large-sized trees 50-80 ft (15-25 m) tall, with short trunks, long branches, and very broad crowns occasionally approaching 150 ft (45.7 m) wide, but with longer trunks and narrower crowns in some older woodlands, occasionally to 115 ft (35 m) tall. Very large, old trees can have trunks exceeding 10 ft (3 m) in diameter. Wood can lack obvious or distinct growth rings, especially towards the southern part of its range (Tomlinson, 1986). Short root suckers often forming near the trunk. Bark is gray, very dark brown, to black, and scaly to blocky. Young twigs tan to pale gray, covered in short hairs, becoming darker and nearly smooth in the second year. Buds small, red-brown, rounded. Leaves thickened, shiny on the upper surface, the lower surface pale with short hairs but green and without hair in shade- grown leaves. Leaves 1.4-3.5 in (35-90 mm) long, 0.8- 1.5 in (20-38 mm) wide, usually rounded to oblong, without teeth, but some summer growth and growth on juvenile trees often with toothed leaves (Nelson, 1994) that can be smaller. Leaves appearing evergreen but actually deciduous for a few weeks during flowering in the early spring, although trees from further north within its natural range show some natural tendency toward partial deciduousness in the colder months (Cavender- Bares, 2007). Male and female flowers inconspicuous, borne separately on the same tree (typical of all oaks), female flowers wind-pollinated, solitary or in clusters of 2-3 or rarely up to 5, male flowers in catkins of several flowers. Acorns stalked, solitary or up to five in a cluster, acorn caps 0.3-0.6 in (8-15 mm) long and wide, bowl- to goblet-shaped, with numerous, tiny, sharp-pointed scales, nuts barrel-shaped to egg-shaped, 0.6-1.0 in (15-25 mm) long, dark brown to black. Seedlings with a swollen primary root shortly after germination. For detailed descriptions see Correll & Johnston, 1970; Nixon & Muller, 1997; Miller & Lamb, 1985; Stein et al., 2003; Tomlinson, 1986. Quercus virginiana is one of several species of similar oaks contained within Quercus series Virentes, which also includes: Q. brandegeei, a small to medium-sized tree with very elongate acorns, of lower elevations in mountainous areas in southernmost Baja California, Mexico (Roberts, 1989; Wiggins, 1980); Q. fusiformis (Quercus virginiana var. fusiformis), the Texas live oak, perhaps the most cold-hardy member series Virentes (Diggs et al. 1999), a solitary-trunked to thicket-forming, small to large-sized tree or rarely a shrub, bearing somewhat elongated acorns, in various soil types and rock outcrops (especially limestone and granite), of southwestern Oklahoma, central and southern Texas, and northeastern Mexico; Q. geminata (Q. virginiana var. geminata, Q. virginiana var. maritima), the sand live oak, a thicket-forming, shrub to medium-sized tree with leaves with in-rolled margins often resembling upside-down boats, of deep, dry, sandy soil in the outer coastal plain from Mississippi to North Carolina; Q. minima (Q. virginiana var. minima), the dwarf live oak, a low, rhizomatous shrub forming dense colonies, and usually with toothed leaves, in somewhat moist, sandy soil, with a similar distribution to Q. geminata; Quercus oleoides, a small to large-sized tree of seasonally dry subtropical and tropical forests from eastern Mexico south to Costa Rica; and Q. sagraeana (Q. oleoides var. sagreana, Q. virginiana var. sagreana), a medium to large-sized tree of sandy to rocky soils in flat to hilly areas of western Cuba (Borhidi, 1996), which appears to be derived from Q. virginiana (Gugger & Cavender-Bares, 2011). For a detailed summary of Quercus series Virentes see Muller (1961). Quercus virginiana is known or presumed to hybridize with Q. alba, Q. bicolor (an artificial hybrid, Q. × nessiana), Q. lyrata (Q. × comptoniae), Q. macrocarpa (Q. × burnetensis), Q. minima, Q. sinuata, and Q. stellata (Q. × harbisonii). Quercus virginiana hybridizes with Q. fusiformis across of central Texas, leading to much confusion between these two species (Jones, 1975; Nixon & Muller, 1997; Simpson, 1988). Quercus virginiana also seems to hybridize occasionally with Q. geminata (Cavender-Bares & Pahlich, 2009). The largest known living specimen of Quercus virginiana is in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana (American Forests, 2015), with a height of only 68 ft, (20.7 m) but a crown spread of 139 ft (42.4 m) and a trunk circumference of nearly 39 ft (11.9 m). Because this tree has several trunks it may not be a single tree. Close competitors are a three- trunked tree in Waycross, Georgia, and a single-trunked tree in Seminole County, Georgia (Georgia Forestry Commission, 2015). The Waycross tree is 77 ft, (23.5 m) tall, an average crown spread of 155 ft (47.2 m) and a trunk circumference of 35 ft (10.7 m). The Seminole county tree is 89 ft, (27.1 m) tall, an average crown spread of 147 ft (44.8 m) and a trunk circumference of about 32 ft (9.8 m). Distribution: Native to the southeastern coastal plain of the United States, from southeastern Virginia southward to south Florida and west to eastern Texas (Nixon & Muller, 1997). It is common to abundant throughout much of its natural range, but less so at its northeastern extremity in Virginia where it is relatively rare except along the coast near Virginia Beach (Weakley et al., 2012). For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Warm-temperate to subtropical or marginally tropical woodlands, savannas, and grasslands, on slightly damp to somewhat dry clay, loam, or sand, occasionally on limestone. Perhaps best represented in evergreen woodlands on maritime barrier islands, but also in various forest types in peninsular Florida, including those of floodplains, moist hammocks, and upland tropical hammocks on limestone (Clewell, 1985; Harms, 1990; Nixon & Muller, 1997). Throughout much of its range its branches are hosts to many epiphytic plants, especially bromeliads (such as Spanish moss, Tillandsia usneoides), ferns (typically resurrection fern, Pleopeltis polypodioides), and orchids.

Adaptation

Live oak is tolerant of a wide range of soil moisture, pH, and compaction (Dirr, 1998), and survives both significant drought and short periods of flooding (Allen & Kennedy, 1989; Carey, 1992). Live oak also shows moderate tolerance of both freezing weather and salt, although more northern populations seem to be more tolerant (Kurtz et al., 2013). This species also exhibits a combination of both intolerance and tolerance of fire, with the above-ground parts of a tree damaged or killed by even low-intensity ground fires, with smaller trees most susceptible to damage, but the root crown surviving and producing many suckers after a fire (Harms, 1990; Carey, 1992). This species is native to a region likely to experience hurricanes, which this species withstands well (Harms, 1990), perhaps due to its very hard wood. Live oaks in south Florida recovered within several years after Hurricane Andrew in 1992 (Douglas Goldman, personal observation).

Uses

The wood of this species is brown to nearly white (darker in heartwood than sapwood), close-grained, and is extremely hard, strong, and heavy (Austin, 2004; Panshin & de Zeeuw, 1970). Dry wood has a density of around 56-63 lb/ft3 (900 - 1009 kg/m3, 0.9-1.0 g/cm3; Alden, 1995; Cavender-Bares et al., 2004; National Hardwood Lumber Association, 2014), and probably even higher (Steve Cross, personal communication, August, 2015), making its wood one of the densest of North American tree species. Consequently it is appropriate to use for “articles requiring exceptional strength and toughness” (Panshin & de Zeeuw, 1970). It is used for pulp and firewood (Duncan & Duncan, 1988), durable items like furniture and flooring (Meier, 2015), but it is best known for its use in ship construction (Wood, 1981), especially in the 18th and 19th Centuries. The combination of the hardness of the wood, resistance to decomposition (Meier, 2015), and the various branch and trunk shapes (Wood, 1981), made Q. virginiana an ideal choice for use with various robust structural elements of wooden ships, prior to the use of steel. The USS Constitution earned the name “Old Ironsides” when cannon balls launched by the HMS Guerriere in August, 1812, were observed bouncing off the Constitution’s hull, which was partly constructed of live oak (Wood, 1981). Events like this only reinforced the value of live oak timber, and helped result in the establishment in 1828 of the first Federally-owned and managed tree farm in the United States, the Naval Live Oaks, now part of Gulf Islands National seashore near Pensacola, Florida (Snell, 1983; Wood, 1981). On occasion live oak is still used for ship construction. Beginning in 2011, the Maritime Museum of San Diego began constructing a replica of the Spanish galleon San Salvador, which in 1542 was the first European vessel to visit the west coast of what would become the United States (Maxwell, 2012). Live oak is still used on occasion for the construction of some smaller modern vessels, such as shrimp boats (Wood, 1981). Live oak commonly is used in horticulture within its native geographic range, and occasionally in areas beyond that have similar climatic conditions. First cultivated in 1739 (Olson, 1974), it is used in municipal plantings, around commercial establishments, and around homes. It is hardy in areas as cold as USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 7 (Dirr, 1998), even though it is native to Zones 8-10, but it is susceptible to damage from freezes that last for several days (Simpson, 1988). Its broad shape make it an elegant horticultural subject, and it can grow rapidly with adequate moisture (Osorio, 2001), especially when young. It is tolerant of diverse soil types and some variation in soil moisture, and transplants relatively easily, especially when young (Dirr, 1998; Rehder, 1940). Attempts have been made to find cold-hardy live oaks that will survive as far north as Boston, Massachusetts (Dosmann & Aiello, 2013). Although this species is cold-hardy beyond its native range, its evergreen habit can make it more susceptible to branch breakage from ice or snow accumulation (Douglas Goldman, personal observation). Live oak also has been used for reforestation in areas where it is climatologically suitable. It has been used for revegetating well-drained portions of bottomland hardwood areas in the lower Mississippi valley (Allen & Kennedy, 1989), as well as coal mine sites in eastern Texas (Davies & Call, 1989). The acorns of this species, and the related Q. fusiformis, are valuable forage for waterfowl, turkey, wild pigs, raccoons, and deer (Allen & Kennedy, 1989; Elston & Hewitt, 2010 [treated as Q. virginiana]), with this species readily established by animal dispersal (Osorio, 2001).

Ethnobotany

Historically, the swollen, tuber-like roots of live oak seedlings were fried and eaten (Nixon & Muller, 1997). The Houma tribe of southeastern Louisiana used a decoction of the bark of live oak for treating dysentery (Moerman, 1986). Several old live oak trees have special historical significance. See Miller & Lamb (1985) for a list of such specimens.

Status

Threatened or Endangered: This species is not listed as threatened or endangered by the Federal government, or by any state where it naturally occurs. Wetland Indicator: In all regions where it naturally occurs, this species is considered FACU, or a facultative upland species, usually not occurring in wetlands (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2014). However, it is considered an upland plant (UPL) in the Western Mountains, Valleys, and Coast region (specifically Utah), where it is an introduced species.

Planting Guidelines

Live oaks grow rapidly when planted, provided they are given adequate water and are not root-bound in pots prior to planting (Osorio, 2001). They are best transplanted when small (Dirr, 1998), and transplanting success is greatest when planted in raised beds in sandy soil, with root collars at the surrounding soil level but not above or below it (Bryan et al., 2011). Because this species forms large root systems and wide crowns with age, these factors should be considered when planting live oaks in areas where they could obstruct vehicular traffic or damage sidewalks (Osorio, 2001).

Management

Live oak that are well-established under favorable conditions or habitats are very resistant to competition from other plant species (Harms, 1990). When used in habitat revegetation projects this species establishes better when inoculated with mycorrhizae (Davies & Call, 1990). In areas managed for game or browsing animals, the related species, Q. fusiformis, can out-compete many valuable forage plant species, even though it is a valuable browse and mast species itself (Fulbright & Garza, 1991 [treated as Q. virginiana]). Controlling Q. fusiformis thickets with fire only increases the density of these thickets (Springer et al., 1987 [as Q. virginiana]). However, with Q. fusiformis, abundant browsing can inhibit the establishment of mature trees (Russell & Fowler, 1999).

Pests and Potential Problems

Live oak is susceptible to oak wilt (Diggs et al. 1999; Peacock & Smith, 2013; Sinclair et al., 1987), caused by the fungus Ceratocystis fagacearum. The disease is spread by burrowing beetles or root grafts between trees. Symptoms can occur in part or all of the tree, consisting of leaf necrosis, with larger leaf veins becoming yellow to bronze, and gradual branch die-back over one to a few years. Oak wilt can be contained by removing infected trees, injection of systemic fungicides, or breaking root grafts by trenching (Peacock & Smith, 2013; Sinclair et al., 1987). Bot canker, a fungal disease caused by Diplodia corticola and D. quercivora, has been found to cause significant branch dieback in live oak (Dreaden et al., 2014; Mullerin & Smith, 2015). The fungus Taphrina caerulescens causes leaf blister, resulting in leaf deformities or some defoliation (Harms, 1990). Xylella fastidiosa causes bacterial leaf scorch in live oak, resulting in branch die-back (McGovern & Hopkins, 1994). Competition with other species can have a negative impact on live oak establishment. For example, the presence of the invasive Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolius) significantly inhibits the establishment of live oak seedlings (Nickerson & Flory, 2015). Live oak twigs often are damaged by gall formation, and although insecticides can control gall-forming wasps, reinfestation from untreated trees makes gall inhibition more difficult (Platt Bird et al., 2013). The roots of live oaks can be attacked by the larvae of a large beetle, the live oak root borer, Archodontes melanopus, resulting in deformed growth of effected trees (Harms, 1990).

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

The related species, Q. fusiformis, can invade grasslands, reducing available forage for wildlife (Fulbright & Garza, 1991 [as Q. virginiana]).

Control

Please contact your local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what works best in your area and how to use it safely. Always read label and safety instructions for each control method. Trade names and control measures appear in this document only to provide specific information. USDA NRCS does not guarantee or warranty the products and control methods named, and other products may be equally effective.

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Quercus virginiana average 352 cleaned seeds per pound (Olson, 1974), Propagation by seed is preferred (Dirr, 1998), and healthy acorns germinate rapidly and in high percentages (Olson, 1974), Acorns don’t require vernalization, but desiccated or frozen acorns become inviable, and those stored unfrozen in moist peat tend to germinate but bear soil-borne fungal pathogens (Dirr & Heuser, 1987), so planting acorns shortly after collection is preferred, Propagation by cuttings, especially from younger trees, has had some success (Dirr & Heuser, 1987), but cuttings made from root suckers have rooted at very high rates and in turn have produced few root suckers themselves (Niu & Wang, 2007), Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Live Oak., Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) Several live oak cultivars are available, One of the most popular is High Rise (‘QVTIA’), a selection with rapid vertical growth which is well-suited for narrow planting spaces, For a summary of live oak cultivars see Coder (2010) and Dirr (1998), Cultivars should be selected based on the local climate, resistance to local pests, and intended use, Consult with your local land grant university, local extension or local USDA NRCS office for recommendations on adapted cultivars for use in your area,

Literature Cited

Alden, H.A. 1995. Hardwoods of North America. General Technical Report FPL-GTR-83. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, WI. Allen, J.A., & H.E. Kennedy, Jr. 1989. Bottomland hardwood reforestation in the lower Mississippi Valley. Slidell, LA: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Wetlands Research Center; Stoneville, MS: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experimental Station. American Forests. 2015. National Big Tree Program. www.americanforests.org Austin, D.F. 2004. Florida Ethnobotany. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. Borhidi, A. 1996. Phytogeography and Vegetation Ecology of Cuba. Second Edition. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, Hungary. Bryan, D.L., M.A. Arnold, A. Volder, W.T. Watson, L. Lombardini, J.J. Sloan, A. Alarcón, L.A. Valdez- Aguilar, & A.D. Cartmill. 2011. Planting depth and soil amendments affect growth of Quercus virginiana Mill. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 10: 127- 132. Carey, J.H. 1992. Quercus virginiana. In:

Fire Effects

Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). [Accessed 25 August 2015] http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis Cavender-Bares, J., K. Kitajima, & F.A. Bazzaz. 2004. Multiple trait associations in relation to habitat differentiation among 17 Floridian oak species. Ecological Monographs 74: 635-662. Cavender-Bares, J. 2007. Chilling and freezing stress in live oaks (Quercus section Virentes): intra- and inter- specific variation in PS II sensitivity corresponds to latitude of origin. Photosynthesis Research 94: 437- 453. Cavender-Bares, J., & A. Pahlich. 2009. Molecular, morphological, and ecological niche differentiation of sympatric sister oak species, Quercus virginiana and Q. geminata (Fagaceae). American Journal of Botany 96: 1690-1702. Clewell, A.F. 1985. Guide to the Vascular Plants of the Florida Panhandle. Florida State University Press, Tallahassee, FL. Coder, K.D. 2010. Live oak: historical ecological structures. Document WSFNR10-23. Tree Dendrology Series, Warnell School of forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. Correll, D.S., & M.C. Johnston. 1970. Manual of the Vascular Plants of Texas. Texas Research Foundation, Renner, TX. Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) Press, Ft. Worth, TX. Davies, F.T., Jr., & C.A. Call. 1989. Mycorrhizae, survival and growth of selected woody plant species in lignite overburden in Texas. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 31: 243-252. Diggs, G.M. Jr., B.L. Lipscomb, & R.J. O’Kennon. 1999. Shinner & Mahler’s Illustrated Flora of North Central Texas. Dirr, M.A. 1998. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants. Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses. Stipes Publishing, Champaign, IL. Dirr, M.A., & C.W. Heuser, Jr. 1987. The Reference Manual of Woody Plant Propagation: From Seed to Tissue Culture. Varsity Press, Athens, GA. Dosmann, M.S., & A.S. Aiello. 2013. The quest for the hardy southern live oak. Arnoldia 70: 12-24. Dreaden, T.J., A.W. Black, S. Mullerin, & J.A. Smith. 2014. First report of Diplodia quercivora causing shoot dieback and branch cankers on live oak (Quercus virginiana) in the United States. Plant Disease 98: 282. Duncan, W.H. & M.B. Duncan 1988. Trees of the Southeastern United States. University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia. Elston, J.J., & D.G. Hewitt. 2010. Intake of mast by wildlife and the potential for competition with wild boars. Southwestern Naturalist 55: 57-66. Fulbright, T.E., & A. Garza, Jr. 1991. Forage yield and white-tailed deer diets following live oak control. Journal of Range Management 44: 451-455. Georgia Forestry Commission. 2015. Georgia’s Champion Tree Program. [Accessed 28 August 2015] http://www.gfc.state.ga.us

Conservation

Service, National Plant Data Team. Greensboro, NC.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Steve Cross, Iron City, GA, for helpful discussions about this species and its uses, and Ramona Garner and Gerry Moore for reviewing this manuscript. Published: September 2015. Edited: September 23, 2015, D.H.G. For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or Conservation District at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/ and visit the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov/ or the Plant Materials Program Web site: http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov. PLANTS is not responsible for the content or availability of other Web sites.

Fact Sheet

Alternate Names

Virginia live oak

Uses

Erosion Control: This is an excellent species for reforestation to prevent erosion on originally cleared land for agriculture. It also has the potential for revegetating coal mine spoils. Wildlife: Live oak acorns are an important food source for many birds and mammals including northern bobwhite, Florida scrub jay, mallard, sapsuckers, wild turkey, black bear, squirrels, and white-tailed deer. This species provides cover for birds and mammals. The rounded clumps of ball moss found in live oak is necessary for nest construction. Timber: The wood of live oak is heavy and strong but of little use commercially. Recreation and Beautification: Live oak is used for shade and as an ornamental. It is considered “one of the noblest trees in the world and virtually an emblem of the Old South.” Today live oaks are protected for public enjoyment.

Status

Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Description

Live oak, is most commonly found on the lower coastal plain of the southeastern United States. The tree can grow up to an average of 50 feet in height and 36-48 inches in diameter, but can have trunks over 70 inches in diameter. The bark is furrowed longitudinally, and the small acorns are long and tapered. The bark and twigs are dark to light grayish color and become darker with age. The leaves are thick, shiny, and dark green on top, lighter below. Small flowers are produced when new leaves are grown. The acorn is about 1 inch long with a turban-shaped cup, and is somewhat narrowed at the base. There are approximately 352 acorns per pound. Root crowns and roots survive fire and sprout vigorously.

Adaptation and Distribution

Distribution

Distribution

Live oak grows in moist to dry sites. It withstands occasional floods, but not constant saturation. It is resistant to salt spray and high soil salinity. Live oak grows best in well-drained sandy soils and loam but also grows in clay and alluvial soils. Live oak has moderate shade tolerance. Live oak is distributed primarily throughout the Southeast. For a current distribution map, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Website.

Establishment

Live oak has male and female flowers on the same plant. Germination occurs shortly after seed fall if the site is moist and warm. Live oak is fast growing if it well-watered and soil conditions are good. Seedlings can grow 4 feet in the first year. Under ideal conditions, a live oak can attain a trunk diameter at breast height (dbh) of 54 inches in less that 70 years. Live oak sprouts from the collar and roots, and forms dense clones up to 66 feet in diameter.

Management

Once established, live oak withstands competition, It is extremely salt tolerant and this resistance may account for its dominance in many climax coastal forests in the northern part of its range, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Live Oak., Dense stands of live oak reduce forage production for livestock, Live oak is extremely hard to kill because of its vigorous root sprouting ability,

Plant Traits

Growth Requirements

| Temperature, Minimum (°F) | 7 |

|---|---|

| Adapted to Coarse Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Fine Textured Soils | Yes |

| Adapted to Medium Textured Soils | Yes |

| Anaerobic Tolerance | Medium |

| CaCO3 Tolerance | None |

| Cold Stratification Required | No |

| Drought Tolerance | Medium |

| Fertility Requirement | Low |

| Fire Tolerance | Low |

| Frost Free Days, Minimum | 240 |

| Hedge Tolerance | Medium |

| Moisture Use | Medium |

| pH, Maximum | 7.3 |

| pH, Minimum | 4.5 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Maxim | 1200 |

| Planting Density per Acre, Minim | 300 |

| Precipitation, Maximum | 70 |

| Precipitation, Minimum | 32 |

| Root Depth, Minimum (inches) | 40 |

| Salinity Tolerance | Low |

| Shade Tolerance | Intermediate |

Morphology/Physiology

| Bloat | None |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | None |

| Resprout Ability | Yes |

| Shape and Orientation | Rounded |

| Active Growth Period | Spring and Summer |

| C:N Ratio | High |

| Coppice Potential | Yes |

| Fall Conspicuous | No |

| Fire Resistant | No |

| Flower Color | Yellow |

| Flower Conspicuous | No |

| Foliage Color | Green |

| Foliage Porosity Summer | Moderate |

| Foliage Porosity Winter | Porous |

| Foliage Texture | Medium |

| Fruit/Seed Conspicuous | Yes |

| Nitrogen Fixation | None |

| Low Growing Grass | No |

| Lifespan | Long |

| Leaf Retention | Yes |

| Known Allelopath | No |

| Height, Mature (feet) | 50.0 |

| Height at 20 Years, Maximum (fee | 25 |

| Growth Rate | Rapid |

| Growth Form | Single Stem |

| Fruit/Seed Color | Brown |

Reproduction

| Vegetative Spread Rate | None |

|---|---|

| Small Grain | No |

| Seedling Vigor | Low |

| Fruit/Seed Period End | Fall |

| Seed Spread Rate | Slow |

| Seed per Pound | 352 |

| Propagated by Tubers | No |

| Propagated by Sprigs | No |

| Propagated by Sod | No |

| Propagated by Seed | Yes |

| Propagated by Corm | No |

| Propagated by Container | Yes |

| Propagated by Bulb | No |

| Propagated by Bare Root | Yes |

| Fruit/Seed Persistence | No |

| Fruit/Seed Period Begin | Spring |

| Commercial Availability | Routinely Available |

| Bloom Period | Early Spring |

| Propagated by Cuttings | Yes |

Suitability/Use

| Veneer Product | No |

|---|---|

| Pulpwood Product | Yes |

| Post Product | No |

| Palatable Human | No |

| Palatable Browse Animal | Low |

| Nursery Stock Product | Yes |

| Naval Store Product | No |

| Lumber Product | Yes |

| Fuelwood Product | High |

| Fodder Product | No |

| Christmas Tree Product | No |

| Berry/Nut/Seed Product | No |