Jack Bean

Scientific Name: Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Usda Symbol | CAEN4 |

| Group | Dicot |

| Life Cycle | AnnualPerennial, |

| Growth Habits | Forb/herbVine, |

| Native Locations | CAEN4 |

Plant Guide

Alternate Names

Common Names: jack-bean sword-bean coffee bean wonder-bean giant stock-bean horse-bean horse gram Scientific Names: Canavalia ensiformis var. truncata Ricker Dolichos ensiformis L.

Uses

Commercial crop: Outside of the United States both young pods and green seeds are eaten as a vegetable. Seeds are also used as a coffee substitute. The mature bean contains potentially harmful saponins, cyanogenic glycosides, terpenoids, alkaloids, and tannic acid (Udedibie and Carlini, 1998) and must be cooked before eating. There is also pharmaceutical interest in the use of C. ensiformis as a source for the anti-cancer agents trigonelline and canavanine (Morris, 1999). Jack bean seed has been promoted in developing nations as a potential source of affordable and abundant protein. It has 29.0% protein content (Adebowale and Lawal, 2004). Livestock feed: In the United States, jack bean is grown mainly as animal feed. Grazing animals do not prefer jack bean to other green manures (Bunch et al., 1985) and although nutritious, it is coarse and unpalatable (Allen and Allen, 1981). Forage yields have reached roughly 8– 10 tons/ac (FAO, 2012) and 15 tons/ac in Hawaii (Allen and Allen, 1981). The plant has also been used as silage and the seeds are ground for livestock. Adding molasses to jack bean seed meal may help increase its palatability (FAO, 2012). Seed meal may be toxic if too much is consumed and should either be heat-treated to destroy potentially lethal enzymes or limited to 30% of the ration (FAO, 2012). Moist heat is more effective at destroying trypsin inhibitors in C. ensiformis than dry heat (Udedibie and Carlini, 1998). Caution should be used when using the seed as human food or animal feed. The most harmful antinutritional protein, concanavalin A, is somewhat protected from heat treatment (Udedibie and Carlini, 1998). Even minute amounts of this protein may be harmful to animals. Cover crop/green manure: As a cover crop jack bean produces phytochemicals that act as a pesticide, bactericide, and a fungicide (Morris, 1999). The canopy of jack bean can establish 85% cover 60 days after emergence and produces roughly 4,915-6,250 lb/ac of dry matter (Bayorbor et al., 2006; Florentin et al., 2004). It has been used successfully to fix nitrogen and control weeds under fruit trees (Bunch et al., 1985). Jack bean can fix between 167–205 lb N/ac (Bayorbor et al., 2006; Benjawan et al., 2007). It works well suppressing vigorous weeds, such as Pennisetum spp., and can provide rapid ground cover in agricultural plantations (Kobayashi et al., 2003). Because jack bean has been shown to produce large amounts of biomass in both sun and shade, it has potential for use in silvopastoral systems (Bazill, 1987). Soil biofumigant: Incorporating jack bean dry matter into the soil has reduced root galling in tomatoes and increased tomato plant height and weight (Morris and Walker, 2002). Jack bean has been successfully used to increase yield and to suppress nematode (Pratylenchus zeae) populations and root necrosis when intercropped with maize (Arim et al., 2006). Farmer Participatory Research (FPR) in Uganda showed that jack bean intercropped with banana, coffee, sweet potatoes, or cassava is a preferred green manure among farmers (Fischler and Wortmann, 1999). However, research by McIntyre et al. (2001) has shown that intercropping banana with jack bean had no beneficial effect on nematode populations. Aquaculture: Detoxified jack bean seed has been used successfully as a high protein fish meal substitute in tilapia aquaculture (Martinez-Palacios et al., 1987). Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Guide Phytoremediation: Jack bean can be grown in soils with high lead concentration and has potential to be used for restoration of lead-contaminated soils (Faria Pereira et al., 2010). Wildlife: It is pollinated by solitary bees and carpenter bees.

Ethnobotany

Leaves are spread on leafcutter anthills to eliminate ants (Bunch et al., 1985). In Nigeria, jack bean seed is used as an antibiotic and antiseptic (Olowokudejo et al., 2008). Historically, it was used by native tribes for food and forage in droughty regions of Arizona and Mexico.

Status

Jack bean is an introduced species in the United States. Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values).

Description

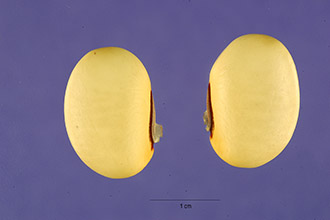

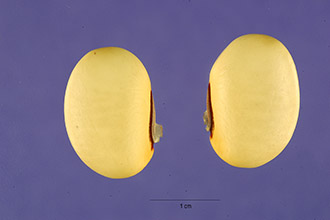

General: Jack bean is an annual or weak perennial legume with climbing or bushy growth forms. It is woody with a long tap root. The 8 in (20 cm) long and 4 in (10 cm) wide leaves have three egg-shaped leaflets, are wedge-shaped at the base, and taper towards the tip. The 1 in (2.5 cm) long flowers are rose-colored, purplish, or white with a red base. It has a 12 in (30 cm) long, 1.5 in (3.8 cm) wide, sword-shaped seedpod. Seeds are white and smooth with a brown seed scar that is about one-third the length of the seed. Its roots have nodules which fix nitrogen. Jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis) in flower. Photo by Christopher Sheahan, USDA-NRCS, Cape May Plant Materials Center. Distribution: Found in the tropics, subtropics, West Africa, Asia, Latin America, South America, India, and South Pacific—mainly in cultivation. It is also grown in the southwestern United States and Hawaii. Canavalia is a pantropical genus that is believed to have originated in the New World based on the large genetic diversity of species in the fossil record (Saur and Kaplan, 1969). For current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Habitat: Jack bean will become established in disturbed upland areas where average rainfall is 28–165 in (NAS/NRC, 1979). It is shade-tolerant (Bunch, 2003), grows best in a temperature range of 57–81°F, and is found at elevations up to 5,900 ft. (NAS/NRC, 1979).

Adaptation

A distinguishing characteristic of this plant is its ability to continuously grow under severe environmental conditions (Udedibie and Carlini, 1998), even in nutrient-depleted, highly leached, acidic soils (NAS/NRC, 1979). Jack bean is drought-resistant and immune to pests (FAO, 2012; Bunch et al, 1985). It can grow in poor droughty soils, and does not grow well in excessively wet soil. It will drop its leaves under extremely high temperatures, and may tolerate light frosts (Florentin et al., 2004).

Establishment

Jack bean should be planted in full sun to light shade in seed beds roughly 1,5–3 ft apart, in late spring/early summer, at 50–60 lb/ac, For weed suppression, researchers have planted 4–5 seeds per square meter (80 lbs/acre) (Bunch, 1985), Its initial growth may be slower in more northern latitudes, and it flowers after 4–5 months (Bunch et al,, 1985), If interseeding jack bean with corn or sorghum, seed should be drilled 15–30 days after sowing the main crop, and after being soaked in water for 24 hours (Bunch et al, Use soil moisture sensors to measure the soil moisture of Jack Bean.,, 1985), Sowing the intercrop at least 15 days after the main cash crop will limit the potential negative effects of plant competition (Caamal-Maldonado et al,, 2001), It does not require staking,

Management

When used as a cover crop or green manure the plant should be terminated mechanically with a roller-crimper or chemically when it first begins to flower. Because jack bean is an annual or very short-lived perennial, it may have to be reestablished each year if used as a weed smothering plant.

Pests and Potential Problems

Jack bean has no significant pests or diseases (NAS/NRC, 1979). The toxicity of the seeds makes them unpalatable to insects and protects them from insect attack (Oliveira et al., 1999).

Environmental Concerns

Concerns

Concerns

The plant can become naturalized beyond its native range. It is not an environmental weed or parasitic.

Seeds and Plant Production

Plant Production

Plant Production

Green pods are produced in 80–120 days and mature seeds produced after 180–300 days (FAO, 2012). Jack bean can produce up to 4,105 lb/ac dry seed (NAS/NRC, 1979), but amounts around 892 lb/ac are more common. There are approximately 658 seed/lb (Acosta, 2009). Cultivars, Improved, and Selected Materials (and area of origin) There has been limited cultivar development of this species. Most plant development has been performed by agricultural experiment stations and has focused on selecting cultivars with low toxicity (NAS/NRC, 1979). Both viny and bushy varieties exist.

References

Acosta, S.C. 2009. Promoting the Use of Tropical Legumes as Cover Crops in Puerto Rico. M.S. Thesis. University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez Campus. Adebowale, K.O, and O.S. Lawal, 2004. Comparative study of the functional properties of bambarra groundnut (Voandzeia subterranean), jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis), and mucuna bean (Mucuna pruriens) flours. Food Res. Int. 37 (4):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.01.009 Allen, O.N., and E.K. Allen. 1981. The Leguminosae: a source book of characteristics, uses, and nodulation. The Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison. Arim, O.J., J.W. Waceke, S.W. Waudo, and J.W. Kimenju. 2006. Effects of Canavalia ensiformis and Mucuna pruriens intercrops on Pratylenchus zeae damage and yield of maize in subsistence agriculture. Plant Soil. 284:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s11104-006-0053-9. Bayorbor, T.B., I.K. Addai, I.Y.D.Lawson, W. Dogbe, and D. Djabletey. 2006. Evaluation of some herbaceous legumes for use as green manure crops in the rainfed rice based cropping system in Northern Ghana. J. Agron. 5(1):137–141. http://docsdrive.com/pdfs/ansinet/ja/2006/137-141.pdf (accessed 7 Jan. 2013). Bazill, J.A.E. 1987. Evaluation of tropical forage legumes under Pinus caribaea var hondurensis in Turrialba, Costa Rica. Agrofor. Sys. 5:97–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00047515 Benjawan, C., P. Chutichudet, and S. Kaewsit. 2007. Effects of green manures on growth, yield, and quality of green okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) Har Lium cultivar. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 10(7):1028–1035. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19070046 (accessed 7 Jan. 2013).Bunch, R. 2003. Adoption of green manure and cover crops. Leisa Magazine. Dec., p.16–18. http://subscriptions.leisa.info/index.php?url=article-details.tpl&p%5B_id%5D=12705 (accessed 7 Jan. 2013). Bunch, R., and ECHO staff. 1985. Green manure crops. Echo technical note. ECHO, North Ft. Myers, FL. http://people.umass.edu/~psoil370/Syllabus-files/Green_Manure_Crops.pdf (accessed 7 Jan. 2013). Caamal-Maldonado, J.A., J.J. Jimenez-Osornio, A.Torres-Barragan, and A.L. Anaya. 2001. The use of allelopathic legume cover and mulch species for weed control in cropping systems. Agron. J. 93:27–36. doi: 10.2134/agronj2001.93127x FAO. 2012. Grassland species index. Canavalia ensiformis. http://www.fao.org/ag/AGP/AGPC/doc/Gbase/DATA/PF000012.HTM (accessed 21 Aug. 2012). Fischler, M., and C.S. Wortmann. 1999. Green manures for maize-bean systems in eastern Uganda: agronomic performance and farmers’ perceptions. Agrofor. Sys. 47:123–138. doi:10.1023/A:1006234523163. Florentin, M.A., M. Penalva, A. Calegari, and R. Derpsch. 2004. Green manure/cover crops and crop rotation in the no-tillage system on small farms. Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock of the Republic of Paraguay and the German Technical Cooperation. http://www.fidafrique.net/IMG/pdf/No-Till_SmProp_Chptr_1AF912.pdf (accessed 7 Jan. 2013). Kobayashi, Y., M. Ito, and K. Suwanarak. 2003. Evaluation of smothering effect of four legume covers on Pennisetum polystachion ssp. setosum. Weed Biol. Manage. 3:222–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1444-6162.2003.00107.x Martinez-Palacios, C.A., R.G. Cruz, M.A.Olvera Novoa, and C. Chavez-Martinez. 1987. The use of jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis Leguminosae) meal as a partial substitute for fish meal in diets for tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus Cichlidae). Aquaculture 68(2):165–175. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(88)90239-6 McIntyre, B.D., C.S. Gold, I.N. Kashaija, H. Ssali, G. Night, and D.P. Bwamiki. 2001. Effects of legume intercrops on soil-borne pests, biomass, nutrients and soil water in banana. Biol. Fertil. Soils 34:342–348. doi: 10.1007/s003740100417 Morris, J.B. 1999. Legume genetic resources with novel “value added” industrial and pharmaceutical use. p. 196–201. In: J. Janick (ed.), Perspectives on new crops and new uses. ASHS Press, Alexandria, VA. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/proceedings1999/v4-196.html (accessed 22 Aug. 2012). Morris, J.B., and J.T. Walker. 2002. Non-traditional legumes as potential soil amendments for nematode control. J. Nemat. 34(4):358–361. http://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/18902/PDF (accessed 7 Jan. 2013). NAS/NRC. 1979. Tropical legumes: resources for the future. Report by an ad hoc advisory panel of the Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation, Board on Science and Technology for International Development, Commission on International Relations, National Academy of Sciences and the National Research Council, Washington, DC. Oliveira, A.E.A, M.P. Sales, O.L.T. Machado, K.V.S. Fernandes, and J. Xavier-Filho. 1999. The toxicity of jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis) cotyledon and seed coat proteins to the cowpea weevil (Callosobruchus maculates). Entomol. Exp. Appl. 92:249–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1570-7458.1999.00544.x Olowokudejo, J.D., A.B. Kadiri, and V.A. Travih. 2008. Ethnobotanical survey of herbal markets and medicinal plants in Lagos Nigeria. Ethnobot. Leaf. 12: 851–65. http://www.ethnoleaflets.com/leaflets/lagos.htm (accessed 22 Aug. 2012) Pereira, B.F.F, C.A. de Abreu, U. Herpin, M.F. de Abreu, and R.S. Berton. 2010. Phytoremediation of lead by jack beans on a Rhodic Hapludox amended with EDTA. Sci. Agric. (Piracicaba, Braz.), 67(3):308–318. doi:10.1590/S0103-90162010000300009 Saur, J. and L. Kaplan. 1969. Canavalia beans in American prehistory. American Antiquity 34(4):417-424. Udedibie, A.B.I., and C.R. Carlini. 1998. Questions and answers to edibility problem of the Canavalia ensiformis seeds—a review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 74:95–106. doi:10.1016/S0377-8401(98)00141-2 Citation Sheahan, C.M. 2012. Plant guide for jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May, NJ. Published March 2013 Edited: 25Feb2013 aym; 25Feb2013 rg; 25Feb2013 sc For more information about this and other plants, please contact your local NRCS field office or

Conservation

District at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/ and visit the PLANTS Web site at http://plants.usda.gov/ or the Plant Materials Program Web site http://plant-materials.nrcs.usda.gov. PLANTS is not responsible for the content or availability of other Web sites.